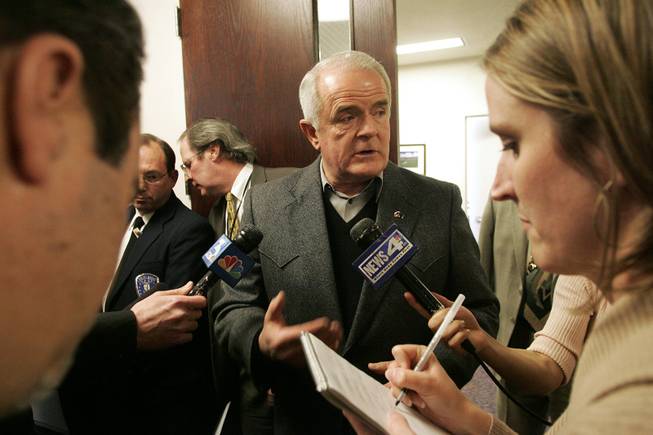

Gov. Jim Gibbons speaks to the media Thursday after what he described as a “cordial” meeting with Republican leaders to discuss differences during Day Three of the special legislative session in Carson City. If Gibbons is re-elected, he will face another four years of difficult budget decisions.

Friday, Feb. 26, 2010 | 2 a.m.

Sun Coverage

Being broke is never fun, as Nevada’s governor and the men who would replace him can attest.

Nevada’s fiscal crisis leaves few good options, forcing candidates for governor to crank up their creativity:

Gov. Jim Gibbons, who has staked his political survival on being a champion of the anti-tax movement, has tried to say increasing the tax bill on mining companies is not a tax increase.

Brian Sandoval, the retired federal judge challenging Gibbons in the Republican primary, has proposed leasing our public buildings to investors, who would in turn lease them back to us.

Rory Reid, the Democratic chairman of the Clark County Commission, has taken a different tack, refusing to propose anything at all.

The Sun asked the three leading candidates how legislators should fill the nearly $900 million budget hole.

Sandoval

Brian Sandoval

Sandoval would get a significant chunk of change by borrowing an idea from Arizona: selling state buildings to investors, and then leasing them. The Sandoval plan has a slight twist, as investors would lease rather than buy the buildings, for a significant upfront fee — $250 million — that would then be recouped from Nevada taxpayers, with interest, over 20 years.

Sun archives

- Bipartisanship emerges in anger at Gibbons over session deadline (2-25-10)

- Democrats: Trim education cuts to 5 percent (2-24-10)

- Gibbons adds to agenda, says session will end by Sunday night (2-24-10)

- Relationship between Gibbons, Raggio shows strain on Day 2 (2-24-10)

- Plan to use cameras to catch uninsured motorists appears dead (2-24-10)

- Gibbons’ budget plan risky in an election year (2-24-10)

- Anti-tax ideology tests Republicans (2-24-10)

- Gibbons pulls senior staff from legislative hearings (2-23-10)

- Gibbons denies, then admits taking texting friend to D.C. (2-23-10)

- Lawmakers to tackle water rights during special session (2-23-10)

- Proposal to close state prison meets opposition (2-23-10)

- Budget crunchtime: Lawmakers set to tackle historic deficit (2-23-10)

Sound like a loan?

“That’s absolutely what it is,” said Le Templar, communications director for the Goldwater Institute in Arizona, named after conservative standard-bearer Barry Goldwater.

“Selling off public assets is fine, but mortgaging your future makes no sense to us. In essence, it’s a tax increase, you just pay it out over time,” he said.

Although liberals are friendlier to deficit spending during times of deep recession, Nicholas Johnson of the liberal-leaning Center on Budget and Policy Priorities doesn’t like the idea either: “Borrowing has gotten too many states in too much trouble,” he said, referring to California, Illinois and New Jersey.

According to The Arizona Republic, the sale and lease-back arrangement yielded $735 million for Arizona, but taxpayers will eventually repay $1.1 billion.

Sandoval defended the plan as a last option: “We’re facing difficult choices. It’s been accomplished in Arizona, it’s going to be done in California. Under a normal circumstance, no, we wouldn’t do this. But it’s better than raising taxes or mass layoffs,” he said.

Sandoval would cut state employee pay, including teachers’ salaries, by 4 percent, to save $212 million. He would also take $110 million from Clark County School District class-size reduction funds and move it to the general fund, and then allow the School District to tap its $1.1 billion capital fund for class-size reduction, reasoning that flat enrollment means the district won’t need to build new schools.

Sandoval would reduce health benefits for current and retired state employees, hoping to save $110 million. He would increase employees’ share of their health care costs and reduce subsidies for retirees.

For some, the changes would be dramatic. Employees could see a $75 to $150 a month hit. Retirees not old enough for Medicare would be thrown into the system without a subsidy, which would cost them $567 a month. For those on Medicare, loss of the subsidy to fill in the gaps when Medicare won’t pay could cost an additional $295 a month.

But the plan may not yield nearly the savings Sandoval claims.

His numbers come from a 2009 legislative report, whose numbers in turn came from the Spending and Government Efficiency, or SAGE Commission.

But the SAGE Commission appears to have overstated, by as much as tens of millions of dollars, the savings to be wrung from the proposed changes. SAGE asserts that the state pays 95 percent of employee health insurance, except the Public Employee Benefit Program Board has reduced that to closer to 85 percent.

Also, SAGE asked the board to report back on predicted savings from four proposed policy changes. SAGE added the four together for its total. Except, there’s some overlap so some savings were counted twice.

The actual savings aren’t known, but could be tens of millions short of the Sandoval estimate, according to benefit program officials.

All told, because his proposal was already well below the total needed, Sandoval appears to be $100 million short — and probably more.

Reid

Rory Reid

Reid declined to provide any specifics, preferring to wash his hands of the whole sordid Carson City mess.

His involvement would be neither constructive nor meaningful, he said.

“Politics should be removed from this, and the Legislature should do its work. And look, Nevada is good at this stuff. Every so often, we take out our bubble gum and Scotch tape, and we patch together a short-term solution, and we move on. But what we really need to do is talk about what we’re going to do in the future so we never face this again,” he said.

As it happens, Reid won’t talk about that either. Although he’s released a detailed plan on economic diversification and job growth, he has thus far refused to lay out solutions to the state’s long-term budget needs. He’ll do so before the election, just not yet, he said.

For now, “I want my actions to be the measure of what I would do in this situation.”

Reid and his campaign point out that as a Clark County commissioner he has for years balanced a budget nearly as large as the state’s without raising taxes, even during the recession.

“I’ve dealt with a large and complex budget successfully, and done it in a difficult economy,” he said.

He did this, in part, by putting away 8 percent to 10 percent of tax proceeds into reserves.

Last month he released a plan to renegotiate contracts with county union workers, root out inefficiency in county management and clean up University Medical Center’s books by turning it into a nonprofit hospital.

“We have a crisis, too. And I’m solving that problem, without playing to the bleachers,” Reid said. “I’m going to continue to solve the problem I was elected to solve.”

He also took a shot at Sandoval and Gibbons: “Both released budget plans that cut from education as a first measure. That says something about their priorities. And I think it’s wrong.”

Gibbons

Gov. Jim Gibbons

By now, the details of Gibbons’ plan are fairly well known, as they are the basis for the current special session.

For the tattered remnants of his political operation, it’s been another bad week.

Reducing the deductions that mining companies can take as they compute their tax bill has been widely viewed among anti-tax purists, including Americans for Tax Reform’s Grover Norquist, as a tax increase.

Gibbons had hoped to raise at least $50 million, and in all likelihood mining will take a hit after escaping last session unscathed despite high gold prices and a relatively light tax burden.

Dan Burns, the governor’s spokesman, said the proposal is not a tax increase: “Taking away a deduction is not a tax increase,” he said, comparing the proposal to federal law that eliminated the credit card interest deduction in the 1980s.

Gibbons’ proposal to allow a private company to set up cameras to catch uninsured motorists was dead on arrival at the Legislature. Gibbons’ staff had said the company would guarantee that the state would make money from fines to uninsured motorists and unregistered vehicles; the company agreed to put $30 million in a trust and guarantee Nevada at least that amount.

Legislators were skeptical of the idea, which no U.S. state has attempted.

Burns defended it: “There’s a company that wants to write a check to us for $30 million, and it’ll pay for everything else.” Addressing privacy concerns, he said, “The cameras are actually scanners that see letters and numbers. That’s it.”

Most of Gibbons’ plan entails large cuts to all government, including education and the universities. Gibbons set the target for cuts at 10 percent, saving the state about $380 million. He revised some after legislators and the public protested.

The reversed cuts include housing for the mentally ill and mentally disabled, dentures for the poor and elderly, and day care for adults with disabilities. With those revisions, the governor’s cuts stand at about $340 million.

Gibbons had also proposed an additional $36 million cut to K-12 education. On Monday, his office announced the cut to education would shrink from 13 percent to 10 percent, but Democratic legislators want to add more back to the schools.

Gibbons, with legislative agreement, would also take from various pots of money, including $89 million in funds paid by industries. Another $12.6 million could be taken from the Millennium Scholarship, which helps Nevadans with adequate high school grades pay for college. Taking money from the fund will mean it will run out sooner.

Candidates for governor who think the current mess is a headache will have to consider this: With the state facing massive, long-term deficits, the eventual winner will be sworn in next January and face no choice but to cut still more, or raise taxes.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy