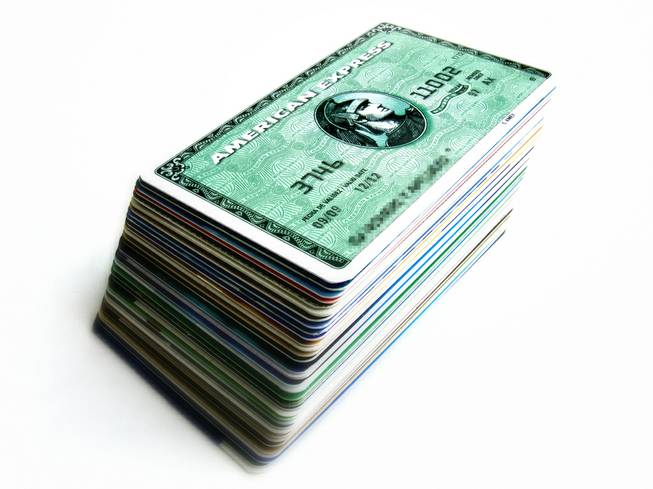

Andres Rueda / flickr.com

Monday, Feb. 15, 2010 | 12:05 a.m.

View the study

Sun Archives

- In cases of ID theft, numbers do lie (3-6-2009)

- Own a business? Be vigilant, thieves are lurking (6-2-2008)

- Here comes more bad news for identity theft victims (5-23-2007)

- Stealing your child's credit (12-11-2006)

Beyond the Sun

The fraud took 48 hours from start to finish — a credit card that was swiped at a high-end fashion retailer in Las Vegas one day was counterfeited and being used two days later, often in Greece, Turkey, Morocco, Germany or Spain.

This is because when the salespeople weren't ringing up customers on the store computer, they were using it to check e-mail and kill time online. One quick click, and an employee downloaded a virus that logged keystrokes and captured credit-card information.

Detectives from Metro's Electronic Crimes Unit eventually traced the security breach to Romania. Romanian coffee shops, actually, where free wireless networks meant anonymous hacking. The Metro detectives found the same ring had cracked into 78 stores across the United States.

Of course, by that time, it was a Secret Service case, so detective Paul Ehlers doesn't know if the Romanian ring was ever taken down. Or if he does know, he won't say.

What he will say, however, is this: "It goes on every day."

Metro's Electronic Crimes Unit is seven detectives strong — two work on child-porn and exploitation cases, the other five work on everything else.

That everything else ranges from the local and palpable (credit-card skimmers hidden in gas-station pay pumps) to the murky Internet intangible (international hackers who are time zones away, hidden behind strings of 1s and 0s.)

And all of it is on the rise.

In 2005, for example, Metro detectives only found one credit-card skimmer hidden in a gas-station pay-at-the-pump card reader. Last year, they found 40. And those, Ehlers emphasizes, are just the ones detectives found — the implication is there are many more still out there, secretly pulling information off magnetic strips and capturing PIN codes with pressure-sensitive punch pads.

The latest credit-card skimmers are actually Bluetooth-enabled, Ehlers says, which means the scam artists can pull up to the gas station and wirelessly download the stolen financial information from the comfort of their cars.

Once thieves have a person's banking information, they can print it on any magnetized strip — a casino room key, perhaps, or a supermarket club card. One Vegas skimmer stole so many credit-card numbers, and printed so many counterfeit cards, that he actually brought a lawn chair to sit on while he ran the cards, one by one, through an ATM machine at night, taking money out of all his hacked accounts.

The stupidity of this move — spending more than an hour in a lawn chair running cards through an ATM machine equipped with a video camera — undermines any notion that you have to be really clever to use a skimmer, by the way.

Meanwhile, the potential for profit is huge.

When detectives searched a storage vault belonging to one card-skimming ring, they found $840,000 in $20 bills and 40 pounds of pure gold bullion inside.

The rings' profits were being hidden in cars and then shipped to small Eastern European towns, where the Secret Service agents who took over the case told Ehlers that dirt roads and donkeys were being replaced with marble banks and Mercedes — the flush of fraud.

At least in these cases, the detectives could see the fruits of their labors, could confiscate the computers and printers and machines that make such fraud possible.

When the cases go online, when it's a matter of viruses and phishing and computer forensics, the bad guys are generally gone before they're caught — they're buried behind Internet anonymizers and computer trails that bounce from Bangladesh to Ukraine to Greece then back to a server in Russia, long since disabled by the time police catch up.

And it's always a matter of catching up. The Metro detectives are, like law enforcement everywhere, outnumbered by "booby-trapped websites," Ehlers says, and viruses that are "silently worming their way through networks via unprotected ports and porous firewalls."

Depending on whom you ask, millions — or maybe tens of millions — of American computers are infected with viruses. Hackers can harness these computers like soldiers, Ehlers says, forming "bot armies" that can, without individual users knowing it, collectively overwhelm and crash websites, or distribute spam, or commit "click fraud" — jacking up website hits.

Or they can just mine computers for private information. It's been estimated that at least 245 million people have been exposed in computer data breaches since 2004. Some say that's a conservative estimate, if only because companies probably prefer to keep these things quiet as possible. Data vulnerabilities aren't really great for business.

They aren't easy for police to investigate, either. And even when Ehlers does pinpoint a perpetrator, it's not like he's going to Uzbekistan to make the arrest. Even when it's a local perpetrator, in a country where jails are crowded with people facing violent crime and drug charges, computer crooks and counterfeiters often get probation.

Still, there are small rewards. Ehlers and fellow detectives once found a forgery lab hidden in the staircase of a two-story Henderson home. Another time, they caught a guy running a criminal operation out of an off-strip casino, where he was printing bogus checks — in the casino security tapes, they found video footage of him carrying computer and printing equipment to his room in a wheelbarrow.

— Originally published in Las Vegas Weekly

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy