Lenders with security in less profitable Station properties such as the Wild Wild West fear getting the short end of the stick when assets are distributed.

Friday, Sept. 11, 2009 | 2 a.m.

Station spending plans

- Here’s how Station Casinos wants to spend lenders’ money over a 13-week period, according to a proposed budget the company filed in bankruptcy court in Reno. A minority of lenders with casino collateral disapprove, fearing that the cash drain will hurt their ability to recover what they are owed. Station says the expenditures are necessary to operate the business.

- $500,000 to support Aliante Station, still in “start-up mode” after opening in a recession.

- $2 million for Green Valley Ranch as part of a contingency fund needed to “maintain its position as a luxury resort property.”

- $1.3 million for monthly rent on the company’s posh headquarters in Summerlin.

- $1.1 million to maintain a joint venture to develop a mixed-use project on land accumulated south of Palace Station.

- $4.1 million for the mortgage on land south of the Strip at Cactus Avenue and adjacent to Wild Wild West, where the company intends to build resorts.

- $29.2 million to support development deals with Indian tribes.

- $64.3 million for rent and property taxes paid to the company subsidary owning the four, better-performing casinos.

Sun Coverage

Sun Archives

- Lenders want study on Station's rejection of Boyd, other issues (9-2-2009)

- Judge delays key part in Station bankruptcy case (9-1-2009)

- Creditors probe deal that took Station private (8-27-2009)

- Station’s legal battle heats up in bankruptcy case (8-24-2009)

- Station Casinos swings to loss in second quarter (8-14-2009)

- Boyd still interested in acquiring Station properties (8-5-2009)

- Culinary Union sees shot in Station insolvency (8-3-2009)

- Lenders battling in Station Casinos bankruptcy case (7-30-2009)

- Station Casinos wants out of lease for office space (7-29-2009)

- Station Casinos files for Chapter 11 (7-28-2009)

- Bondholder drops lawsuit against Station Casinos (5-11-2009)

- Station Casinos: Bankruptcy date depends on bondholders (3-18-2009)

- Betting it all on bankruptcy? (2-17-2009)

- Hearing delayed again on Station Casinos site (2-16-2009)

- Boyd responds to Station’s rejection of buyout (3-9-2009)

- Station rejects Boyd’s offer, extends debt deadline (3-3-2009)

- Boyd makes play for Station Properties (2-24-2009)

- Boyd Gaming offers to buy Station (2-23-2009)

- Station responds to lawsuit, misses $15.5M payment (2-17-2009)

Capitalizing on super-low interest rates and a frenzy for Las Vegas real estate, Station Casinos went private in 2007 by accumulating more than $5 billion in debt.

It wasn’t a simple process. Like a layer cake as abstract art, the company split the debt at least nine ways and split its assets three ways, giving three of the lending groups assets as collateral. To create maximum leverage, the owners split the company from the top down by creating an operating company and a property ownership company.

Because lenders typically restrict how much debt any one entity can have relative to earnings, Station moved $2.5 billion in debt to the property ownership level, separating it from another pile of $3.2 billion in debt. Within each group, at least three subgroups share the debt, further spreading risk.

Then along came the recession, which has forced Station, saddled with debt that would have been quickly paid down in a booming economy, to seek bankruptcy protection.

It has triggered a messy fight among creditors, exacerbated by the sheer number of lender groups owed money, that may take a year to sort out.

In one corner of the ring are lenders with the best assets as collateral, giving them the right to take over those casinos as payment for claims. In the other corner: A motley group of dissident investors, including lenders with the right to foreclose on less-desirable casinos as well as unsecured creditors who have no assets backing their claims.

Like sniping vultures circling a carcass, those lenders with more to lose commonly file complaints early in the game, before a company has proposed a plan for reorganization, said Nancy Rapoport, a bankruptcy law professor at UNLV who is not involved in the case.

“They’re jostling for position now because, when the time comes to vote on a plan for reorganization, they want to be in a place where their vote counts, where they will be heard,” Rapoport said.

In recent days, dissident lenders have rolled out bigger guns, claiming the 2007 Station buyout was fraudulent because it was poorly capitalized from day one. If successful, “fraudulent conveyance” claims can force lenders with claims on better assets, like Deutsche Bank, to give up their priority and cough up more money for smaller creditors with less collateral. A legal term buried in the laws of each state, fraudulent transfer regulations have become a hunting ground for unhappy creditors in Nevada.

Unfortunately for dissidents, bankruptcy isn’t exactly a democratic process. It’s intended to favor debtors like Station, which has 120 days after filing to present a reorganization plan for court approval. All creditors get to vote on a reorganization plan, which is approved based on a majority vote among each class of creditors. But those holding a minority of the debt have less leverage and can be forced to accept decisions they don’t like. The bankruptcy judge could force smaller creditors to accept cents on the dollar if he determines that there’s not enough money to pay everyone.

Deutsche Bank says the Station deal wasn’t overleveraged because it was financed with 40 percent equity and that the recession wasn’t the bank’s fault. Moreover, the bank says second-tier lenders signed away their rights to complain when they entered into the loan and accepted Deutsche Bank as their agent.

For all the bickering, winners and losers are emerging in what is one of the state’s most high-profile bankruptcies.

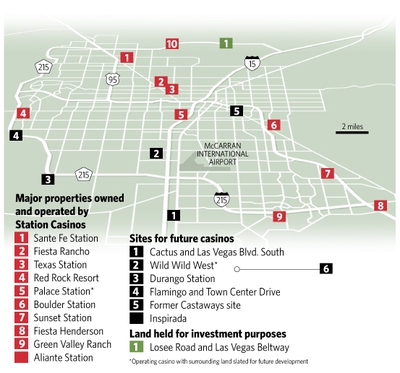

A group of banks led by Deutsche Bank probably stands the best chance of recovering what its owed, according to bankruptcy experts not involved in the case, because, by virtue of their loan agreement, they are first in line to take possession of four of the company’s most profitable casinos — Red Rock, Palace Station, Boulder Station and Sunset Station — as collateral. Lenders say these properties represent at least 60 percent of company earnings, before interest, taxes and certain other expenses.

Lenders with collateral in the remaining properties owned and operated by Station, including Santa Fe Station, Texas Station, Fiesta Rancho, Fiesta Henderson and small casinos such as the Wild Wild West and Wildfire, may recover less of what they are owed after the lenders with top assets are paid. Like those creditors who don’t have any assets securing their claims, these lenders worry about getting the short end of the stick.

Green Valley Ranch and Aliante, two of Station’s newer casinos, were separately financed and are not part of the bankruptcy.

Lenders with more to lose are leveling complaints against Deutsche Bank, the bank that arranged various loans for Station before the company went private and which is a primary lender holding collateral in the four choice casinos.

Lenders with liens on second-tier assets and those with no assets as security say they didn’t have a voice in pre-bankruptcy discussions about how to reorganize the company because Deutsche Bank shut them out.

As an administrator of various loans now in dispute, Deutsche Bank is supposed to represent all lenders. It’s conflicted, according to dissident lenders, because most of the bank’s money lent to Station is concentrated in the loan secured by the four more lucrative casinos.

As an example of the bank’s conflicted position, according to dissidents, Deutsche Bank promoted Station’s plan to forgive more than $1 billion in company debt, in part by paying bottom-tier lenders pennies on the dollar due them, even going so far as to approach select lenders with money in exchange for their support. The lesser lenders rejected the idea, forcing Station to reorganize its debts in bankruptcy court.

Dissident lenders also question the cash Station is spending to stay in business during bankruptcy protection, saying it is draining money that is due creditors.

A majority of lenders with collateral in Station properties (dissidents represent a minority of secured lenders) signed off on Station’s plan to spend, over the next 13 weeks, more than $100 million for various ongoing operational costs, including development deals with Indian tribes and a mortgage on land for future casinos.

Such expenditures, negotiated with lenders months before bankruptcy, are essential to preserving the company’s business and ensuring a successful reorganization, Station Casinos Chief Financial Officer Tom Friel said in a statement filed with the court.

Dissident lenders also question a corporate structure in which the operating company pays rent to the entity holding the four more lucrative casinos. The structure, dissidents say, diverts money belonging to all creditors to Deutsche Bank to pay the mortgage on four casinos that probably aren’t worth the $2.4 billion mortgage on them.

Lenders without collateral are piling on, as they are less likely get their money after secured lenders ahead of them are paid.

It’s unknown at this early stage whether lenders at the front of the line will cooperate with Station to own or run the casinos, or whether lenders will retain an outsider or even entertain a sale of multiple casinos to another casino operator such as Boyd Gaming, which has cash in hand and is eager to pick up properties from its competitor.

With Station’s attorneys now doing the talking in court, it’s also unknown whether Station will stay in control by playing any of its numerous wild cards, which include cash raised from the sale of any of its numerous casinos, more than 500 acres of undeveloped land it owns or controls in Las Vegas, Northern California and Reno, or money raised from the Fertitta family’s Ultimate Fighting Championship franchise.

What’s clearer to bankruptcy observers is that the fight for cash is going to get messier before it is settled.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy