Jeanmarie Schirling has fostered about 200 children over the past 11 years. She says foster parents in Clark County who work with a nonprofit agency benefit from having “another set of eyes and ears” to help handle problems.

Friday, Oct. 30, 2009 | 2 a.m.

Sun Archives

- Gains in child protection threatened (5-7-2009)

- County Commission chairman rejecting child welfare cuts (11-19-2008)

Having taken in some 200 foster children over the past 11 years, Jeanmarie Schirling knows the rewards of providing a safe home and some measure of joy to children who have known so little happiness.

But being a foster parent is not easy. It takes a big investment to do it well. Foster children can require extra supervision and attention and often have medical and psychological needs. And taking care of any child, of course, also entails various expenses — clothes, food, toys.

Schirling says some people will either give up being foster parents or not give it a try if the pay and assistance offered are cut.

The Legislature’s budget tightening resulted in a 42 percent cut in funding that affects a particular group of foster homes — the 100 or so that take in sibling groups and rely on private nonprofit agencies to provide training, home visits, school consultation, tutoring, mentoring and other help to those foster parents and children.

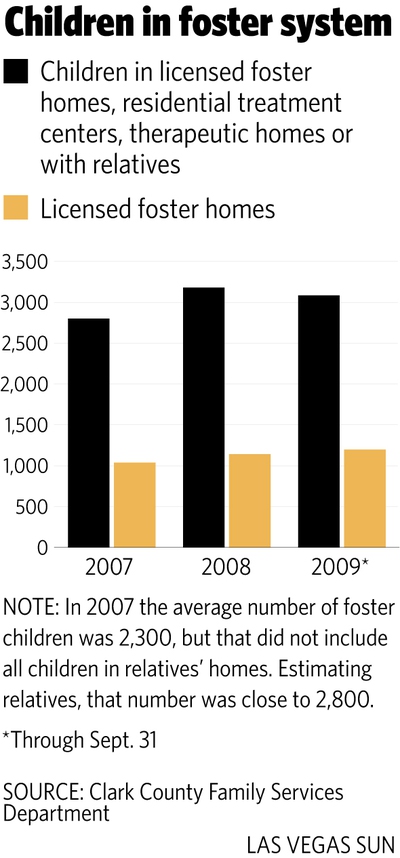

Tom Morton, director of Clark County Family Services, said those private groups became part of the county’s safety net a few years ago, when the county’s Child Haven shelter was overcrowded and the county faced threats of lawsuits over it.

Relatively quickly, he said, Child Haven’s numbers decreased. As a result money budgeted for Child Haven was reallocated for other foster care needs. That included payments to the agencies — there are about seven in Clark County — to help with particularly needy children or sibling groups of foster children.

But because the Legislature has cut money that would have supported Child Haven, Family Services is set to reduce its payments to those agencies.

Last week, Morton’s department presented county commissioners with a plan to decrease the stipend paid to the agencies from $65 per child per day to $40. Rough estimates are that about half of that money goes to the foster homes.

Jennifer Bevacqua, division director for one of those agencies, Olive Crest, pleaded with the commission not to reduce the stipends.

“For three years, no one has disputed we have had great outcomes for children,” Bevacqua said, speaking on behalf of the other agencies. “We’ve set a standard and expectation of care and now they’re saying, ‘You’ve done such a great job, here’s the cut.’ We don’t want to go backward.”

Commissioners agreed. They told county staff to find $240,000 to cover the Family Services Department’s payments retroactively from Oct. 1 through the end of November. The hope is that by the end of November, the county will be able to persuade the state’s Interim Finance Committee to come up with roughly $1.5 million to $2 million needed to maintain the $65 per child stipend paid to the agencies.

Morton has a problem with that.

He notes that the agencies keep a certain amount, then pay $35 to $40 for each foster child each day. He added, however, that foster parents who work directly with Clark County caseworkers, and take in the same types of children handled by the agencies, get just $22 to $24 per child.

“It’s a matter of fairness,” he said.

Anita Stephens, 41, who has three sibling foster children, works directly with the county. She doesn’t think “it makes sense” that she is paid less than foster parents who work with an agency. The agencies “add extra layers,” but she’s not sure that means they provide better service.

“If you get a good caseworker you’ll get good help, but that can be found in the Department of Family Services as well as the agencies,” she said.

Bevacqua said foster parents appreciate the extra attention agencies provide. Olive Crest caseworkers, for example, visit their foster homes once a week, while county caseworkers make visits about once a month, Bevacqua said.

“These parents need that support and training and a lot of other things that we do,” she said.

Schirling, reached Thursday on her way to court to testify in a case involving the birthparent of one of her foster children, said she’d like to work with an agency “because there’s always another set of ears and eyes. If there are any issues, they are there to help.”

Morton said that while he has “always been in favor of public-private partnerships, it has to be done at a rate the state and the county can afford. We were able to pay those rates during a crisis time. It’s not a crisis time right now.”

Morton sees another possible solution down the road. In about a year, his department will be ready to assume many of the responsibilities that the seven foster agencies handle today.

And if the state’s Interim Finance Committee doesn’t grant Family Service more money, those parents can “either absorb the cut or they return the children and say ‘We’ll no longer care for them at that rate.’

“But I’d like to believe that these parents are doing this out of care and concern for children rather than economic interests.”

Foster mom Schirling says the one benefit of lowering the payments would be if “it weeds out those who are only in it for the money.”

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy