A tutor at UNLV helps a biology major from Thailand with a calculus problem this month. The university wants to learn more about students who need such aid.

Sunday, Oct. 18, 2009 | 2 a.m.

In Today's Sun

- Mentors key to helping students succeed (10-18-2009)

Neal Smatresk

Sun Archives

- Nearly half of Nevada students need remedial courses (1-6-2006)

- State scholarship won't cover remedial classes (6-16-2005)

- UNLV wants to get away from the basics (12-5-2001)

- Basic training: UNLV bucks trend by embracing remedial courses (6-29-1997)

Sun Coverage

Beyond the Sun

Walt Rulffes

UNLV is about to launch what may be its most important research project ever: Why are so many freshmen not ready for college even though their high school grades suggest they are?

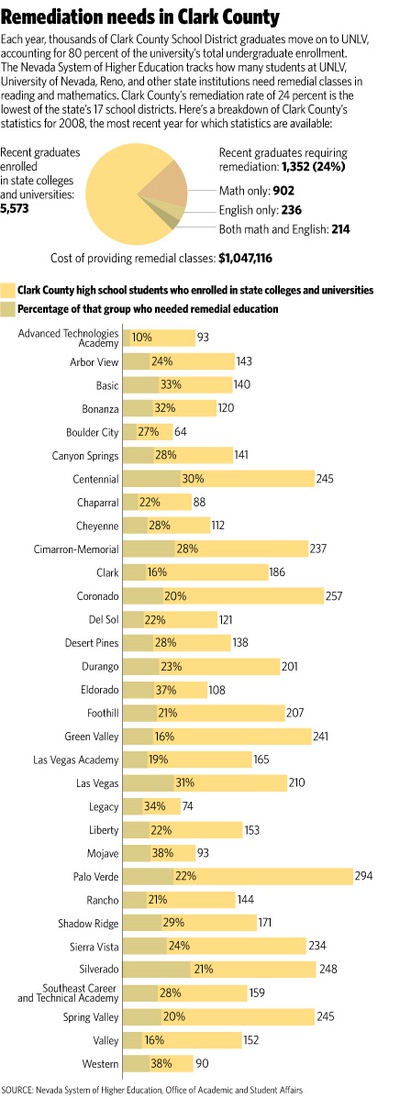

In 2008, more than a third of the Nevada high school graduates who enrolled at the state’s universities and colleges required remedial classes in English and mathematics, at a cost of over $2 million.

Neal Smatresk, the UNLV president, says the problem needs to be addressed clinically, the way doctors examine patients.

“As soon as those students get here we need to diagnose, prescribe and treat,” Smatresk said. “If we come up with the right prescription to fill those critical skills gaps, then I think we can give our students an edge.”

Other public universities — notably in California — are addressing the problem of poorly prepared college freshmen, but Smatresk has a unique laboratory at his disposal: the Clark County School District, the pipeline for 80 percent of UNLV’s undergraduate population.

That will allow UNLV to mount what may be the most aggressive initiative in the nation to address the problem, Smatresk said.

The scope and reach of UNLV’s research — including evaluating every incoming freshman to reverse-engineer his academic upbringing — will create a new paradigm in studying student remediation, Smatresk said.

Key to the effort: a series of brief tests, now being introduced, to identify gaps in the reading comprehension skills of incoming freshmen that might not show up in their high school transcripts or college entrance exam scores. A new assessment of incoming students’ math skills is expected to be introduced next fall.

Smatresk has proposed levying a $1-per-credit-hour surcharge per undergraduate student. A typical freshman class is about 5,000 students, and UNLV has a total of about 22,000 undergraduates. Smatresk said he expects the surcharge to raise about $500,000 a year, which would support the entire initiative, including assessments, remedial classes, the Academic Success Center and tutoring. Smatresk has the backing of student leadership, and will ask for Board of Regents support in December.

Data gathered from the academic assessments would be shared with school districts and could help educators identify and correct patterns of weakness, whether it be general flaws in teaching philosophies or student study habits.

Clark County Schools Superintendent Walt Rulffes said the research findings could offer important insight into the root causes of the problems requiring remediation.

The possibility that the district will be able to identify clusters of underachieving students, and trace them to not only individual campuses but individual classrooms, has Clark County’s teachers union on edge.

Students arrive at school with a host of challenges, many of which cannot be solved by even the best of classroom instruction, said Ruben Murillo, president of the Clark County Education Association.

“We would be more than willing to work with the university and the district in terms of truly identifying what impacts a student’s performance and readiness for college,” Murillo said. That assessment, he said, should include “a component that deals with their home life and a lack of family support.”

Julie Greenberg, senior policy director for the National Council on Teacher Quality, a Washington, D.C.-based advocacy group, agrees that identifying teachers with the strongest — and weakest — track records of producing college-ready students doesn’t tell the whole story.

“You can have a fantastic teacher doing a perfectly competent job but the kids are still below grade level,” Greenberg said. “There’s a lot of confounding variables.

“For a lot of these kids, the problems started in elementary school — you were off track long before your senior year,” said Greenberg, who taught secondary math for 13 years in Maryland. “You were passed along and passed along, and all the cracks and gaps were papered over.”

Smatresk, who served as UNLV’s executive vice president and provost before being appointed president in August, said the ultimate purpose of his initiative is to reduce the need for incoming UNLV freshmen to take remedial classes.

“It’s not about blaming teachers, it’s about revealing the problems we have and then honestly developing strategies to resolve them,” Smatresk said. “We would like to call it an attempt to help the teachers.”

Rulffes was willing to go even a step further.

There are unquestionably socio-economic factors in student achievement, Rulffes said, and elements such as parental involvement and truancy play a role. If the remediation study points to problems in classroom instruction, that shouldn’t be viewed as an indictment, Rulffes said.

“If anything, I would say it’s really the district’s fault and the community’s fault for not properly supporting teachers,” Rulffes said.

Measuring whether high school graduates are truly ready for college has flummoxed educators for years.

Plenty of freshmen with strong track records of academic success, and who do well on SAT or ACT college-admission tests, struggle at the college level.

For 30 years, Nevada has tied its high school diploma to passing a statewide proficiency exam, in addition to completing required classes. But the exams are based on the state’s K-12 standards, and are not aligned with the expectations of the higher education system, experts say.

Indeed, about 40 percent of Nevada’s current math proficiency exam is based on fundamental skills that students are supposed to have acquired by eighth grade. The U.S. Education Department has told Nevada it must revise the exam so that only high school-level material is included. The new, more difficult version debuts next year.

“One of the sad things about giving a test like that is that we’re sending deceiving signals to students,” said Nevin Brown, a senior fellow and director of the postsecondary initiative for Achieve, an education think tank created by a coalition of the nation’s governors and business leaders in 1996. “We’re letting them assume that a passing grade means they’re ready for college, which for many of them just isn’t true.”

The problem of Nevada’s underprepared college freshmen has long vexed both K-12 and higher education officials. In 2006, Rulffes and Jim Rogers, then-chancellor of the Nevada System of Higher Education, pledged to take action.

• To weed out borderline students who might not be ready for a more rigorous academic environment, UNLV raised admissions standards, demanding that incoming freshmen have grade-point averages roughly equivalent of a B-minus as opposed to a C-plus. The effect: Students more at risk of failing in college weren’t admitted in the first place.

• The School District now requires all students to take a college prep curriculum — students can opt not to with their parents’ permission — and added a fourth year of mathematics to its graduation requirement. New efforts to help students prepare for college entrance exams, which are used by the higher ed system to determine freshmen class assignments, resulted in higher test scores, district officials say.

• The College of Southern Nevada and Nevada State College began offering more remedial help, as well as expanded dual credit classes for high school students.

In 2006, the Legislature decided it would no longer fund remedial classes at the state’s two universities, UNLV and University of Nevada, Reno, cutting the number of remedial class offerings and resulting in only 8 percent of UNLV freshmen getting catch-up help, compared with 38 percent the previous year. The university still offers a limited number of remedial classes paid for with other funding, with enrollment on a first-come, first-served basis. Students who don’t land a spot at UNLV have to complete remediation elsewhere — such as CSN or NSC — before they can take their first university courses.

Research suggests there is an incentive for universities to offer remedial classes: Students who take them are more likely to graduate than those who need help but don’t. On the flip side, offering remediation on the public’s dime can be the equivalent of double-billing taxpayers for classes that should have been mastered in high school.

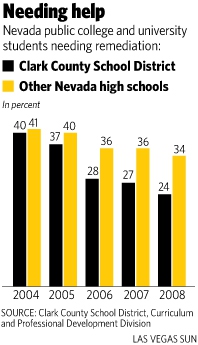

Of the Clark County School District students who graduated in 2008 and went on to state colleges and universities, 24 percent required remediation, a rate that has been steadily declining from 40 percent in 2004.

It’s possible that requiring a fourth year of mathematics has contributed to the lower remediation rate, along with students doing better on entrance exams and UNLV raising admission requirements. But “it’s impossible to know for sure,” said Kim Boyle, director of guidance and counseling for the district. “There are so many contributing factors, you have to be careful when drawing conclusions.”

Based on assessments being used in freshman English classes, about 40 to 50 percent of UNLV’s incoming students need help with reading comprehension skills, said Ralph Reynolds, a professor of educational psychology at UNLV who is overseeing the pilot program for an expanded diagnostic tool.

“Our plan is to follow them not just for this year but all four years,” Reynolds said. “That’s the only way to truly measure how effective our intervention is.”

After identifying which students need help, the university intends to provide tutoring, Reynolds said.

There’s only enough money right now to provide tutoring help to the 70 most needy students of the 2,000 tested since August — a fraction of those who might actually benefit, Reynolds said.

But it’s a good start, Reynolds said, adding that he was grateful to Smatresk for allocating the money for a new program despite the severe budget cuts the university was forced to make this year.

The National Center for Education Statistics reports that about 20 percent of freshmen enrolling in four-year institutions require at least one remedial course.

Although there’s no shortage of conversations about the need for elementary, secondary and higher ed partnerships to address remediation rates, few educational experts are hunting for a solution, said Greenberg of the National Council on Teacher Quality.

“It’s a strangely rational thing for them (UNLV and the School District) to be doing,” Greenberg said with a laugh. “The reality is that there’s a real disconnect between K-12 academic standards and what colleges actually want students to know.”

UNLV’s strategy of diagnosing how students are ill-prepared for college and reverse-engineering their academic experiences is playing out, in various versions, elsewhere.

Since 2004, Louisiana has been tracking the achievement of students whose teachers are graduates of in-state colleges of education. The effort is intended to measure the quality of the preparation program a teacher went through by evaluating the standardized test performance of a new teacher’s students, said Beverly Flowers-Gibson, associate dean of the College of Education at the University of Louisiana-Monroe.

Her campus has received top ratings, indicating the young teachers it produces are scoring as well or better than veteran teachers.

But the evaluations “don’t tell us what we’re doing right,” she said. Other universities call Flowers-Gibson to find out Monroe’s secret formula, only to learn the academic program and approach are similar to what they have in place.

“It would be wonderful if we could say, ‘If you follow these steps in sequence, you will have successful teachers,’ ” Flowers-Gibson said. “But we are not there yet.”

At the least, Clark County schools are trying to better identify poorly prepared college-bound students before they graduate.

An assessment test being developed by the School District will measure reading, writing and math skills of high school juniors. If the results show they are not on track to meet higher ed’s expectations by graduation, the students can use their senior year classes to get up to par.

“If we can identify struggling students when they’re juniors, we can help them use their senior year to shore up their weaknesses,” Rulffes said.

The School District is modeling its assessment of college-bound juniors after a program in California, where more than 60 percent of the 40,000 students admitted to the California State University system each year have needed remedial classes in English, math or both.

California’s high school juniors can take a series of short tests that measure their readiness for college-level work, and use the results to guide their choice of senior-year classes.

While Cal State’s overall remediation rate remains high, there’s evidence at individual campuses that the program is helping.

Kim Grytdahl, principal of Silverado High School, says he likes the sounds of the Cal State assessment test. Last year 21 percent of Silverado’s graduates required remedial classes after enrolling in a state university or college.

There are plenty of students with decent GPAs and passing scores on the proficiency exams who still aren’t ready for the college workload, Grytdahl said.

“It would be great if we could have the data in front of us and say to a kid, ‘Look, you have a decent GPA and you’ve passed the proficiency tests, but based on what our higher ed system says you need to know, here’s what you have to work on,’ ” Grytdahl said. “And they should do it now while it’s free. If they wait until they get to college it’s going to cost them.”

The biggest stumbling block for college-bound students is math. In the Clark County School District, from 86 percent to 90 percent of middle and high-school students fail to demonstrate mastery of the subject on end-of-semester tests.

Smatresk credited the School District for at least being brave enough to conduct such tests.

“If you assess math anywhere in this country, and you do it honestly, you are going to be horrified — because kids aren’t learning,” Smatresk said.

Math professor William Speer, who is leading the team developing UNLV’s new diagnostic math assessment of incoming freshmen, applauds the district for adding a fourth year of math as a graduation requirement.

“It’s not OK to do a statistics class as a junior and then sit out a year because you think you’ve earned a holiday,” Speer said. “You really pay a price for that.”

To Murillo, president of the Clark County Education Association, Smatresk’s desire to help educators improve their knowledge base is “admirable” but fails to take into account a larger reality.

“In my mind that’s putting the blame on the teacher,” said Murillo, whose union represents the majority of the district’s 18,000 licensed personnel. “If the teacher were more prepared, if the teacher had access to workshops, if the teacher did things differently, the student would learn — the truth is what a student does at school is largely determined by their home life.”

The UNLV research may go a long way in validating — or refuting — that contention.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy