Associated press / courtesy of Brooklyn Botanic garden

The bristlecone pine is one of Nevada’s two state trees.

Wednesday, Nov. 25, 2009 | 2 a.m.

Bristlecone pine facts

- Bristlecone pines live only in a few spots in the mountains of the West and Southwest. One species, Pinus longaeva, lives in Nevada, Utah and California.

- Bristlecones have an average age of 1,000 years. The oldest trees can be found near the tree line at between 10,000 and 11,000 feet above sea level. A bristlecone named “Methuselah” in the White Mountains of eastern California, just across the state line from Nevada’s Esmeralda County, is believed to be the oldest single living organism in the world. Based on a core sample, scientists have pegged its age at 4,767.

- One secret to bristlecones’ longevity is their extremely slow growth rate — historically just tenths of an inch in girth each year. Their needles can live for up to three decades, which allows the trees to conserve energy and continue to photosynthesize through extreme weather and drought.

Beyond the Sun

- High Elevation White Pines: Great Basin bristlecone pines

Nevada’s famous Great Basin bristlecone pines are experiencing a growth boom as temperatures have risen in their high-altitude homes. But the cause of the trees’ heyday could also signal that death is finally coming for the bristlecones, the world’s oldest single living things.

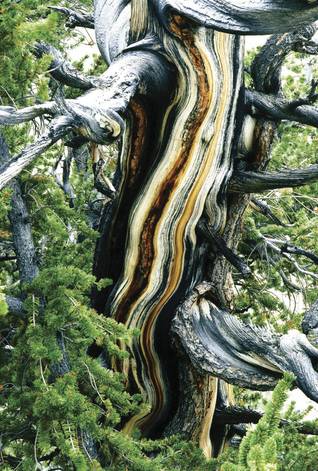

Bristlecone pines look like they could be God’s neglected bonsai, gnarly and twisted but beautiful in a stark way. On the oldest trees, often only a small strip of tissue survives, so that living branches stretch out away from a trunk that otherwise looks mangled and dead. They grow for just a few weeks in summer when the temperature in the high mountains rises above about 45 degrees. But they can withstand the harsh cold, strong winds and frequent droughts of desert mountains to live for thousands of years.

The oldest verified age of a bristlecone was one cut down in Eastern Nevada’s Snake Range in 1964. “Prometheus,” as the tree was named, was at least 4,844 years old. Lately, Prometheus’ relatives have been having the best time of their long lives.

University of Arizona and Western Washington University researchers last week announced the discovery that bristlecones living near the highest tree lines in California and Nevada grew at a far faster rate in the past 50 years than they had in the previous 3,700. Similarly, UNLV researchers recently discovered that bristlecone colonies in the Spring Mountains have greatly expanded their territory, including into lower elevations where they wouldn’t be expected to survive.

Evidence that any high-altitude organism could thrive in warming conditions has rocked the scientific community. Most research on mountain habitats have found animals and plants being forced out of their historical territory by warming trends and melting ice. Mountain animals are moving into even higher altitude habitats, pushing out endemic species and altering the ecosystems.

The Arizona and Western Washington research did not find remarkable impacts on bristlecones living at the middle and lower elevations of the colony, but noted dramatic growth in trees living within 150 meters of the highest tree line. Because the impact was seen only in trees living within these 150-meter buffer areas and not in trees at specific altitudes or specific locations, the researchers posit the growth can be attributed only to higher temperatures, which are felt at a greater level near the tree colony’s boundaries.

Scientists see this as a double-edged sword. For the past 50 years the warmer conditions have extended the trees’ growing season, so they’re growing faster. Because the higher-altitude trees in a bristlecone colony tend to be the oldest, this has meant a dramatic change in the growth patterns of individual trees.

Researchers worry

The relatively sudden, atypical growth of these ancient trees is not just exciting but troubling, some scientists say.

“One of the reasons we think bristlecones can live so long is precisely because it’s so cold up there and they have a short growing season. Now they’re growing like teenagers, and we wonder if they’ll age more rapidly and die more rapidly. That’s the big question,” says UNLV ecologist Scott Abella, who has studied bristlecones in the Spring Mountains above Las Vegas and in Arizona’s San Francisco Mountains.

And it’s not just how they’re growing, but also where they’re growing that has researchers scratching their heads. The Arizona and Western Washington studies indicate the bristlecones are doing well at higher altitudes and will follow the trend of species moving higher up mountains as the globe warms. But that usually means leaving the lower-altitude habitats behind.

That’s not happening in the Spring Mountains.

“Unlike what you’d expect, they’ve expanded their habitat,” Abella says. “They’ve gone down in elevation. They’re expanding and broadening their habitat at a time when you’d expect to see it start moving up the mountain.”

Researchers in UNLV’s Desert and Dryland Research Group have spent the past year poring over maps and old records and collecting hundreds of core samples of bristlecones. And although they’re still crunching numbers, the initial results are surprising. Bristlecones in the upper Kyle Canyon and Lee Canyon have tripled in number in the past 140 years. In some areas they’ve found the number of trees is 10 times what it was in the 1880s. Abella says the same trend is being seen in Northern Arizona’s bristlecones.

This trend seems to have more to do with the way existing forests have been cleared than it does with global warming. Loggers cleared the endemic ponderosa pine in parts of the Spring Mountains between 1870 and 1880. In the years since, the U.S. Forest Service and other agencies have cleared the area of brush to prevent forest fires. All of that made space for baby bristlecones and prevented forest fires that would have killed the vulnerable saplings.

Warming bodes ill

So researchers understand the opportunity bristlecones had to significantly increase their ranks. But they have yet to figure out how the trees have been able to survive the higher temperatures at the lower elevations.

“They’re moving down to areas that you wouldn’t think would be climatically good for them, especially since temperatures have warmed,” Abella says. “It’s almost a train wreck situation. You wonder what’s going to happen to them with climate change. You wonder if they’re going to survive climate change.”

That’s because while these mountain ranges have become warmer in the past 50 years, allowing the trees to grow for longer periods of summer, the effects of global warming aren’t expected to be conducive to bristlecone growth over the long run. Think of this period as the bristlecones’ winter vacation in Florida — a little sun and warmth is rejuvenating, but too much heat for too long spells disaster.

Rainfall and snow patterns are expected to change and severe droughts are expected to become more frequent. In Southern Nevada, precipitation is expected to decrease 3 percent to 7 percent and precipitation could come at different times of year. The trees depend on a predictable precipitation pattern: deep snow in the winter that soaks down to the trees’ roots as it melts in late spring and sporadic heavy rain in the summer that sustains the trees through the height of growing season. If precipitation came in the wrong form at the wrong time, the trees might not get enough moisture to survive. So far, drought has meant less snow in the West and more evaporation. If that trend continues, it could be a huge problem for bristlecones, Abella says.

At the same time, rising temperatures are expected to eventually make the mountains too hot for the trees. The year-round temperature is expected to rise in these areas by 2 to 3 degrees. That could make bristlecone survival at the lower elevations impossible.

The prospect of extinction of a species whose individual members have been able to survive for millennia is staggering for scientists who study them.

They are, after all, “a living record” of the history of the world, Abella says.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy