An airplane flies over the Carol C. Harter Classroom Building Complex at UNLV on Thursday. An uptick in air traffic over the campus has not gone unnoticed by some at the school, but the runway repaving that is to blame is set to end May 1.

Tuesday, March 10, 2009 | 2 a.m.

Sun Archives

- Panel hears arguments in McCarran flight path case (10-23-2008)

- New-route noise lights up airport hotline (5-11-2008)

- Too noisy for neighbors (11-1-2005)

In the past few months the airport has turned UNLV into “Jet-Wash Tech,” aka “Runway U.”

At least that’s how professor Vernon Hodge sees it — and hears it.

“Almost every day the planes scream over the campus every 30 seconds,” by Hodge’s count. “I can even hear them in my office in the massive cement Chemistry Building, beating the windows” (which are behind cement shields).

“Universities are famous for peaceful settings that aid in inducing a creative atmosphere,” Hodge continued.

Having worked at UNLV for more than 25 years, though, Hodge knows his school has always had the airport as its neighbor. McCarran, just southwest of the campus, had been the county’s commercial airport for nearly a decade by the time the university opened on Maryland Parkway in 1957.

Hodge’s gripe is that the noise has gotten so much worse.

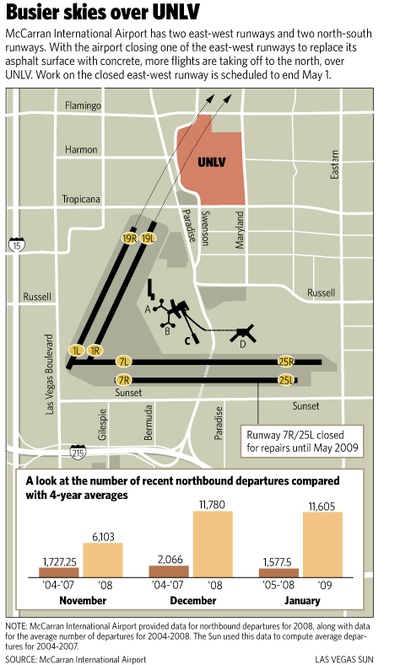

The reason: On Nov. 1, the airport shut down one of its two east-west runways to replace its asphalt with a more durable concrete surface. That means more flights are taking off from remaining airstrips, including two running from south to north that send planes roaring over UNLV.

In January, the most recent month for which McCarran provided figures, northbound departures numbered 11,605, more than seven times the January average for the previous four years. In December, when Hodge e-mailed his complaint to the Sun, northbound departures numbered 11,780, nearly six times the December average for the previous four years.

The good news for the campus community is that work on the decommissioned east-west strip is scheduled to end May 1, after which the volume of air traffic over UNLV should fall back to levels seen before the runway closure.

Randall Walker, Clark County aviation director, said he understands why people complain about the noise. But he points out that the direction planes go is not arbitrary. The Federal Aviation Administration decides where to send the jets. Landing and departure configurations, designed to maximize the number of flights able to come and go, take into account the strength and heading of the wind.

Back when UNLV opened, the airport had fewer daily flights. The first university buildings sat on the side of campus farthest from McCarran, and as UNLV professor Eugene Moehring writes in his book on the school’s history, “the occasional propeller flights of 1955 hardly posed a problem for instruction in classrooms along the west side of Maryland Parkway.”

Over the years, however, as Las Vegas grew, UNLV added buildings to the south and west, closer to the runways and the noise. As Walker put it, “The university kind of expanded itself into this problem.”

On campus today, how much you notice the din of the air traffic depends on several factors — which way your office or classroom faces, how thick the walls of your building are, how long you’ve been at the university (students and employees alike report that after the initial shell shock, they learn to tune out the airplanes).

One recent afternoon, senior Jamie Gifford reclined on a bench by the main library, absorbed in her copy of Jane Austen’s “Pride and Prejudice” and unfazed by passing jets producing sounds ranging from moderate rumblings to chainsaw-esque whirring. Like many on campus, Gifford says she has not noticed a change in the number of flights overhead. The planes haven’t bothered her, except on rare occasions when teachers held class outside. “We couldn’t hear,” she said.

Likewise, Helen Wing, an assistant professor in the Juanita Greer White Life Sciences building near Hodge’s chemistry building, pays attention only if a plane emits an “unusual” sound.

To the west, however, in the Carol C. Harter Classroom Building Complex, some people find the air traffic harder to ignore. Jefferson Kinney, for instance, inhabits an office with a window facing the Thomas & Mack Center, from behind which airplanes emerge, looming large.

Kinney, an assistant professor of psychology, stood in the parking lot behind the complex with a Radio Shack decibel meter one recent Monday. A US Airways plane passing overhead registered at 92 decibels on the ground, about the volume of a lawnmower for its operator. Less than 30 seconds later, another jet flew over the campus at 80 decibels. Soon after, a 90-decibel American Airlines flight went over.

But the noise is actually louder over by Life Sciences, where Kinney maintains a lab and an Allegiant airliner thundered by at 97 decibels.

Kinney sounded apologetic when complaining about his airborne tormentors. “I know that the reality is that we live in a tourist city with an airport in the middle of town and that these flights are necessary for our economy,” he e-mailed the Sun in late February.

Nevertheless, like Hodge, Kinney wondered about the worsening racket.

“There are numerous studies on the effects of chronic loud noise on stress levels and overall physiological function,” Kinney noted. “If the noise is loud enough to set off a car alarm, then it cannot be a good thing for people walking around campus.”

Sun reporter Joe Schoenmann contributed to this story.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy