Sunday, June 21, 2009 | 2 a.m.

Sun Archives

- Despite fiscal problems, Harrah's seeks to expand holdings (6-2-2009)

- Station expects extension in talks with creditors (5-29-2009)

- Station signs agreement to extend restructuring talks (5-15-2009)

- Harrah's extends debt-exchange offer, deadline (3-26-2009)

- Harrah's owners offer to buy outstanding debt (3-19-2009)

Nevada gaming regulators are famous the world over for legitimizing the gaming industry, rooting out undesirable operators and guaranteeing the integrity of play.

But the oversight isn’t supposed to end there. Because a healthy gaming industry is vital to the state’s economy, the Nevada Gaming Control Board and Commission are responsible for reviewing the financial health of gaming companies.

Why, then, have regulators allowed this to happen:

• MGM Mirage, Nevada’s largest private employer, took on $6 billion in bank debt, most of which was assumed in 2004, to cover the cost of acquiring Mandalay Resort Group and the construction of CityCenter. The company has sold one of its properties and recently underwent a $2.5 billion restructuring to avoid bankruptcy reorganization.

• Private equity firms Apollo Management and TPG Capital purchased Harrah’s Entertainment last year for $30.7 billion, doubling the company’s debt to nearly $25 billion. It’s now struggling to make loan payments.

• Station Casinos owners Frank and Lorenzo Fertitta joined with real estate investment firm Colony Capital to take the company private, leaving it with crushing debt. The company has missed bond payments and is working on a prepackaged bankruptcy reorganization proposal.

Those debt loads, combined with a decline in tourism brought on by the recession, have forced the companies to lay off thousands of employees and halt or scale back expansions and new projects. The result has been a deepening of the economic downturn in Nevada.

Some gaming experts and industry players say Nevada regulators dropped the ball, despite a road map from their counterparts elsewhere and case studies here. New Jersey, for instance, adopted tougher standards for financial stability two decades ago, after highly leveraged Atlantic City casinos suffered a wave of bankruptcies and restructurings.

In stark contrast, Nevada has taken a “laissez faire” approach to regulation, said D. Taylor, head of the Culinary Union, which represents 55,000 casino and restaurant workers on the Strip and downtown.

“The idea that regulators would defer judgment on financial matters runs contrary to the reasons regulators were put there in the first place,” Taylor said. “It’s incumbent on regulators to keep the industry in the best possible shape. Instead, I think they’ve abdicated all responsibility. It’s not just private equity. Several companies have gotten out there on a limb. And that’s not good for the industry, the state or the citizens of Nevada.”

Regulators say that in the case of MGM Mirage, the company’s borrowing fell outside their purview because the key players were licensed.

Regulators did review the Station and Harrah’s leveraged buyouts. After checking the corporate math, they deferred to experts, the companies themselves, which took on enormous debt assuming the go-go expansion would continue.

Had those companies stuck with their traditionally conservative business practices or had regulators forced them to exercise greater caution, the threats to their survival would have been greatly diminished.

In 2008 Strip casino revenue fell to $6.1 billion. That’s about what they won in 2005, a boom year. Had operators not taken on such massive debt in the intervening years, they could have absorbed such a hit last year.

But gaming experts say Nevada regulators side with the market.

“Nevada’s approach has been to let people invest in the state,” said Mark Clayton, a gaming lawyer and former Control Board member who approved the deals. “If they’re right they enrich themselves and the state. If they’re wrong, they bear the brunt of the loss.”

He added: “I get leery when regulators start to interject into the business decisions of successful individuals. There were a lot of intelligent, successful investors who put a lot of money at risk (with Harrah’s and Station). They are the ones who have 15 MBAs and financial experts looking at these deals.”

To be sure, Nevada regulators, by law, are charged with ensuring that financing is “adequate for the nature of the proposed operation and from a suitable source.”

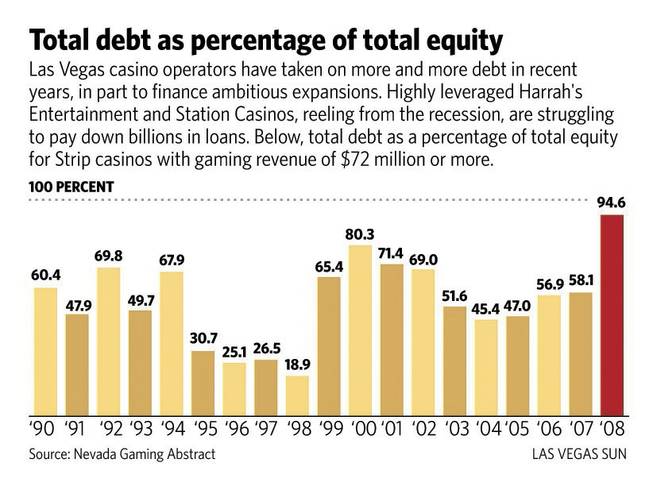

Dennis Neilander, chairman of the Control Board, said the agency hired experts to analyze the Harrah’s and Station deals. They concluded the companies’ debt-to-equity ratios were less than those of companies in similar deals, Neilander said.

No one, he said, could have predicted the credit crunch and depth of the recession when the deals were approved in late 2007. “The companies’ assumptions were reasonable at the time,” he said. “Our view as regulators is that it’s up to the market and the companies’ business plans as to whether they are as successful as they think they’ll be.”

At the International Conference on Gambling and Risk Taking last month at Lake Tahoe, the man who drafted New Jersey’s standards chided Nevada regulators for failing to heed an early warning sign: the 2001 bankruptcy of the Aladdin. Financial consultant Eugene Christiansen said that although one cause of the casino’s collapse was a flawed design, it also had a fundamental financial flaw: It was highly leveraged, suffering from less-than-projected cash flow before falling into bankruptcy.

“The Nevada Gaming Control Board and Commission might have taken a lesson from the Aladdin experience, and made a serious effort at understanding the implications,” he said. Instead, Christiansen said, regulators regarded the event as “the result of design errors that were well understood by other licensees and would not be repeated.”

Eight years later Las Vegas has “taken on the appearance of the Aladdin writ large,” he said.

Nevada might do well to consider stricter financial regulations, Christiansen said.

Regulators here, however, are not looking back, even as they assemble a team of securities experts, auditors and other staff to oversee a string of casino bankruptcy court filings and major debt restructurings. Neilander said regulators stand by their analysis and approval of the Harrah’s and Station deals.

If anything, a greater burden will be on applicants to show adequate financing in today’s tough financial environment, he said.

His view illustrates the difficult line regulators walk in a state overly reliant on the industry they oversee. The Gaming Control Act, passed in 1949, makes state authorities part public advocate, part industry booster.

The law says a regulator’s job is to “protect the public health, safety, morals, good order and general welfare of the inhabitants of the State, to foster the stability and success of gaming and to preserve the competitive economy and policies of free competition of the State of Nevada.”

Initially concerned with ridding casinos of mob influence, regulators started looking at operators’ finances in 1955, after a series of casino failures. In 1969 the Legislature passed the Corporate Gaming Act, allowing publicly traded corporations to own casinos for the first time without requiring their shareholders to undergo licensing investigations. Legislators did so with great caution, expressing concerns that “speculative fever” in gaming stocks would result in economic failures.

Following years of success, both casino companies and gaming regulators got caught up in the housing bubble — and the attendant mind-set, said Steve Kaplan, a finance professor and private equity expert at the University of Chicago.

“Las Vegas and gambling had gone in one direction for 20 years, and that one direction had been up,” he said. “The view was, this was a business that could take on a healthy amount of debt and that demand would continue to be there.”

Bill Eadington, a University of Nevada, Reno, economist and director of the school’s Institute for the Study of Gambling and Commercial Gaming, said the economy was sending “obvious signals” in fall 2007 as Harrah’s and Station sought regulatory approval — in the form of the worsening subprime mortgage crisis. Still, the financial markets had yet to react and investors were willing to pour money into the deals.

Gaming stock prices peaked in October 2007, as Station went before regulators. The following month gaming revenue on the Strip dropped nearly 20 percent from a year earlier, beginning a devastating decline.

“There are a lot of smart people who look very foolish in retrospect,” Eadington said. “It’s easier to look at these things later than when the world is on cruise control and everything is going fine.”

In their hearings before Nevada regulators, both Station and Harrah’s used the same phrase to justify their debt: “stable, predictable cash flow.”

During Harrah’s Dec. 5 appearance before the Control Board, Jonathan Halkyard, the company’s chief financial officer, explained that Harrah’s would be adding about $20 billion to its existing debt of $4.5 billion. He called it “a reasonable amount of leverage.”

Halkyard noted that Harrah’s had seen a year-over-year decline in earnings only once in its history — and it measured 7.5 percent. The deal, he said, provided for as much as a 30 percent drop in earnings.

Neilander, the board’s chairman, asked whether the focus on short-term gain would inhibit future growth. Regulators also sought assurances that properties would not fall into disrepair and that the private equity firms would not use Harrah’s as a quick cash machine.

Ultimately, they deferred to the executives’ judgment.

Board member Randall Sayre’s closing remarks exemplified the tone of the proceedings.

“Some of these questions, coming from us from up here, to very articulate and very accomplished individuals, might seem trivial,” Sayre said. “But I have got to say ... Harrah’s is our baby too. We just want to get real comfortable that our new ownership coming in has got the same commitment to its health and growth that past stewardship has had.”

About two weeks later executives went before the Gaming Commission.

Harrah’s Chief Executive Gary Loveman was much more candid, saying the company was betting its very existence on the deal. “I would say you are at risk that if those investments don’t pay off, you will have to license new people,” he said.

Asked about the financial future, especially given the prospect of falling room rates and the worsening subprime mortgage crisis, Loveman said he saw disturbing trends ahead.

“I think the country is facing a very difficult period of time,” he said. “I think consumers and businesses are looking for ways to reduce their spending levels.

“(If) someone says I can’t sell my house and if I had to, I would take a big loss, or my children can’t get a mortgage for their first home, or my job is at risk, I think these kinds of discontinuous events tend to make consumers quite wary, and in turn, the businesses that service those consumers quite wary.”

Nevertheless, Loveman said he was hoping for the best. If interest rates continue to fall and the financial markets remain stable, he said, “I hope we will see ourselves pull forward a little bit (by the) middle of the year.”

The commission approved the deal unanimously.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy