Tuesday, Jan. 6, 2009 | 2 a.m.

Enlargeable graphic

Sun Archives

- Forecast: 1 in 10 Nevadans jobless (1-2-2009)

- A vast hunger for work at In-N-Out cattle call (12-16-2008)

- Longer lines, slimmer hopes (12-7-2008)

- Economy has many enlisting, reenlisting (12-15-2008)

- Numbers tell the story: 900 jobs, 76,400 unemployed (12-7-2008)

Jason Bartoli recently moved back in with his mother.

The move wasn’t something he planned, but the 22-year-old lost his job of 2 1/2 years at Jillian’s in downtown Las Vegas when the all-ages club closed in November, and his job search since then has hardly been fruitful.

“I’ve tried CVS, the local bar, the local pizza joint, even the minimart,” he said. “It’s been pretty tough. Nobody’s hiring.”

Amid the recession, if employers are hiring, studies show it’s likely they’re bypassing workers like Bartoli in favor of those like Arnold Montero, who is 71 and came out of retirement three months ago to supplement his and his wife’s Social Security checks. A former printing press operator, he’s now a part-time greeter at Wal-Mart.

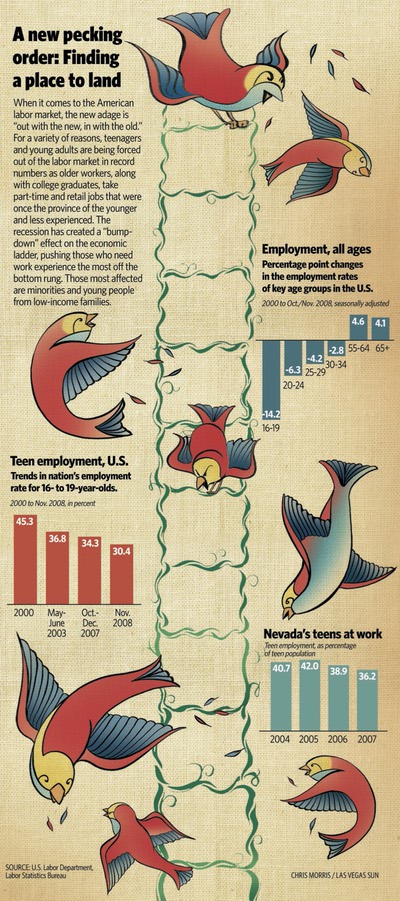

When it comes to the American labor market, the new adage is “out with the new, in with the old.” For a variety of reasons, teenagers and young adults are being forced out of the labor market in record numbers as older workers take part-time and retail jobs that were once the province of the younger and less experienced.

Last summer the teen employment rate was the lowest it’s been in 60 years. Just 32 percent of those 16 to 19 held some form of employment, down 12 percentage points from eight years ago. Nevadans in that age group experienced one of the most dramatic employment drops among their counterparts in the Intermountain West, with a figure that nearly matched the one for the nation. At the same time, the employment rate for those 55 and older — and for those 65 and older — was up between 4 and 5 percentage points.

What does it all mean?

The recession has created a “bump-down” effect on the economic ladder, according to professor Andrew Sum, director of Northeastern University’s Center for Labor Market Studies. Older workers, along with recent college graduates, are kicking the country’s youngest — and most inexperienced — workers off the lowest rungs of the employment ladder.

Studies show minorities and teens from low-income families are disproportionately affected, and Sum predicts the trend, if allowed to continue, will create a new underclass of American youth.

“They’re at the back of the queue and have been pushed out at unbelievable proportions,” Sum said. “For those 16 to 23, labor market success is influenced by what happened to them in previous years. The longer you delay your entry into the labor market the harder it is to find work, particularly for those kids who don’t go on to four-year colleges. The jobs they get will be lower pay, lower quality, and lower on job training.”

In other words: “The kids who need work experience the most get it the least.”

Economic uncertainty has changed the American workforce in profound ways.

Baby Boomers, who represent about 40 percent of the workforce, are rapidly approaching the accepted retirement age of 65 — but data show many won’t be stepping aside at that time, further clogging the job market. Others have retired, only to reenter the workplace.

That’s the case with Montero, the former printing press operator who had been retired for more than a year before deciding he needed to go back to work and got hired at Wal-Mart.

In Nevada, AARP found that 21 percent of its members were “extremely likely” to work after retirement, 11 percent were “very likely” and another 15 percent were “somewhat likely.” That survey was conducted in fall 2006, and those numbers have only increased since the economy began tanking, said spokeswoman Deborah Moore Jaquith. Nationwide, 70 percent of older workers plan to work into their retirement years, the AARP says. And no wonder: Twenty percent of Boomers said they had stopped contributing to retirement plans and 27 percent said they were having problems paying rent and mortgages.

With payrolls shrinking and the labor pool expanding, employers can afford to be selective, Sum said. Sum recalled asking a retail store manager why he had hired only college graduates. The response: “Because I can.”

Not that college grads aren’t suffering, too. Although an overwhelming majority of recent college graduates have found work, between 35 percent and 40 percent of them have taken jobs not requiring a college degree — further displacing younger workers.

Prototypical jobs for inexperienced teenagers, such as bagging groceries, are now being advertised on Web sites geared toward older workers. For example, Vons grocery store has posts for Las Vegas-area positions on RetirementJobs.com.

The Web site has seen a huge increase in traffic this year, with the number of people visiting jumping from 150,000 in January to 456,000 in November.

“We began to see a big uptick in the fall as market news from Wall Street caused many to be concerned about a steady flow of funds in retirement,” spokesman Patrick Rafter wrote in an e-mail.

But some seniors discover they can’t keep up in a job market rapidly changing with technology. They find low-skill jobs typically held by teenagers more attractive, especially considering that almost half of those surveyed by the AARP are interested in part-time work. For those interested in obtaining new skills, the group subsidizes temporary employment at participating companies so seniors can get on-the-job training.

According to Sum, employers say older workers best their younger counterparts when it comes to so-called “soft skills,” such as working in groups and taking direction from supervisors.

The trend toward older employees seems certain: According to the Labor Department, by 2016 the 55-and-older workforce will have grown five times faster than the overall labor force.

To be sure, the squeeze felt by younger workers is typical in times of recession. It’s a cycle familiar to Ron Fletcher, longtime chief of field direction and management for the Nevada Employment Department in Southern Nevada. “We find that entry-level positions that were formerly the turf of younger workers, that wouldn’t traditionally have been looked at by older workers, are being viewed by those older workers as a necessity,” he said. “Many people are not taking career jobs. They’re taking assistance employment.”

What’s different this time, Sum said, is the failure of the economy to bounce back for teens and younger workers after 9/11. While payrolls grew in the ensuing years, they didn’t match the recovery levels of the 1980s and ’90s, and the country’s youth, for the first time since the Great Depression, saw no net benefit from new jobs, Sum said. Paradoxically, raising the minimum wage has also hurt younger workers, as employers seek to get the biggest bang for their buck.

All of this has led Sum and others to call on the Obama administration to reinstate a national jobs program to put the country’s youth, particularly those from low-income families, back to work.

“In the short run we need some help from the federal government,” Sum said. “A lot of these kids need somebody to be their broker in the labor market.”

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy