Students pass a statue of the Virgin Mary as they enter the Bishop Gorman High School campus in Summerlin. The $105 million campus, which opened in 2007, was paid for by a combination of contributions, proceeds from the sale of the school it replaced and money from the Catholic Diocese of Las Vegas.

Sunday, Jan. 4, 2009 | 2 a.m.

Beyond the Sun

Related story

St. Bridget altar boy Marcos Mata leads the procession during a recent Spanish language service at the Catholic church near downtown Las Vegas. Once a small chapel that didn't serve many parishioners, St. Bridget a few years ago added a Spanish language Mass, which would become a force in the church's growth. In February the new church was dedicated, and Sundays now feature two Spanish language Masses and a Filipino service. Each Mass attracts hundreds of faithful.

Who attends Catholic schools?

Here’s a look at how Clark County’s Catholic school population compares with the national profile:

U.S. Catholic Education*

Total K-12 enrollment: 2.27 million

Non-Catholic students: 14.1 percent

Minority students: 29 percent

Total schools: 7,378

Elementary: 6,165

Secondary: 1,213

Schools consolidated or closed: 169

New schools opened: 43

Elementary student profile

Non-Catholic: 12.1

Asian: 4.3 percent

Black: 7.5 percent

Hispanic: 13.1 percent

Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander: 0.8 percent

Native American: 0.4 percent

Multiracial: 3.2 percent

White: 70.5 percent

Secondary student profile

Non-Catholic: 18.3 percent

Asian: 4.1 percent

Black: 8.2 percent

Hispanic: 11.8 percent

Multiracial: 2.7 percent

Native American: 0.3 percent

Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander: 0.8 percent

White: 71.2 percent

Clark County Catholic Education

Total enrollment: 3,823

Non-Catholic students: 8.9 percent

Minority students: 43 percent

Total schools: 8

Elementary: 7

Secondary: 1

Schools consolidated or closed: n/a

New schools opened: n/a

Elementary student profile

Total enrollment: 2,691

Non-Catholic: 2.8 percent

Asian: 12.7 percent

Black: 2.6 percent

Hispanic: 18.8 percent

Multiracial: 11.3 percent

Native American: 0.15 percent

Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander: 2.2 percent

White: 52.3 percent

Secondary student profile

Total enrollment: 1,132

Non-Catholic: 22 percent

Asian: 8 percent

Black: 5.3 percent

Hispanic: 12.5 percent

Multiracial: 2 percent

Native American: 0.4 percent

Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander: 3.6 percent

White: 69 percent

* National data from 2007-08 academic year; Clark County data from 2008-09 academic year

Sources: National Catholic Education Association, Diocese of Las Vegas

PAROCHIAL SCHOOLS BY THE NUMBERS

2.3 million — Number of K-12 parochial students across the country today, down from 5.2 million in the early 1960s.

311,356 — Number of K-12 students enrolled in the Clark County School District in September 2008, a 53 percent increase over a decade. The district receives about 12,000 new students per year.

3,823 — Number of K-12 students enrolled in local parochial schools, a figure that has remained stable — even with the addition of a new school — over the past decade.

The Catholic Diocese of Las Vegas, struggling to build enough churches to keep pace with its burgeoning population, has fallen behind in expanding its school system.

During the past decade, the Las Vegas Catholic community has experienced growth other cities could only pray for: More than 300,000 Catholics have moved here, pushing their numbers to an estimated 700,000.

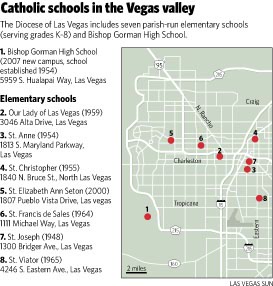

During the same period, however, the church has added only one school and the total number of students served has remained nearly unchanged. Today, about 3,700 pupils attend the seven K-8 schools operated by parishes and Bishop Gorman High School, which is run by the diocese.

That is about equivalent to the student body of one of Clark County’s larger public high schools.

Experts say the inability of a Catholic school system to keep pace with growth deprives the church of one of the surest ways to cultivate its next generation of believers. At the same time, experts say, it also results in a less competitive and less diverse educational environment that ultimately hurts the broader community, regardless of faith.

“We need them not only for competition, but to provide the option for religious and value-based education,” Clark County Schools Superintendent Walt Rulffes said of the region’s Catholic schools.

Bishop Joseph Pepe of the Diocese of Las Vegas said the challenges and costs of accommodating a boom in Southern Nevada’s Catholic population have kept the focus on adding new parishes, not new schools.

With the region’s growth slowing, church leaders are now turning their attention to education, developing a three-year master plan they hope will breathe new life into Southern Nevada’s Catholic school system.

Richard Facciolo, who was superintendent of the diocese schools before becoming president of Bishop Gorman High School in 2008, said he has sensed it’s the right time for Las Vegas Catholics to take a fresh look at education. When he attends parish meetings, the most frequent question from parents is: “When are we getting our school?”

Abundance of volunteers

“Blessed are the clear of heart for they shall see God,” reads calligraphy on a hallway wall inside St. Elizabeth Ann Seton Catholic School in Summerlin.

For a visitor to the immaculate K-8 campus — it opened in 2000 as the valley’s first new Catholic school since 1965 — the contrasts with a typical Clark County public school are striking.

Walls are emblazoned with scripture and inspirational quotes. Parent volunteers are plentiful, assisting teachers in the classroom and helping with other tasks, such as setting out lunches.

It’s these differences that prompted Angela Hart to send her son Keith, a fourth grader, to the school.

Herself a product of the Catholic education system, Hart said parochial schools’ religious instruction and intensive academics prepared her for college, and for life.

“I didn’t think so back then — I didn’t like wearing the uniform, school started earlier and we had different vacations from everybody else,” she said with a laugh. “Now I can see the value.”

There are key differences between these schools and their public counterparts that go beyond religious instruction.

Catholic school class sizes are typically smaller.

St. Elizabeth Ann Seton has 486 students. And Principal Carey Roybal-Benson said he isn’t eager for enrollment to increase. At its current size, he can get to know all the children and their parents.

That wasn’t possible during his three years as principal of nearby Fong Elementary School, where enrollment is nearly twice that of St. Elizabeth Ann Seton.

“Smaller learning communities are much more important than expansion at this point,” Roybal-Benson said. “There’s a real sense here of being one family.”

Public schools typically plead and cajole to get parent volunteers. At parochial schools parental participation is mandatory.

“I don’t think a lot of parents realize the difference in education their kids can get going to a Catholic school instead of a public school. But it takes a lot more effort from everyone,” Hart acknowledges.

Catholic schools are exempt from federal educational mandates. And they do not have to provide specialized services to students with disabilities. Troublemakers and students who come up short academically can easily be expelled.

Long-term studies have found that in urban settings, Catholic schools, because of the disciplined environment, parental involvement and smaller classes, do a better job educating students than the public education system, regardless of the child’s ethnicity or socio-economic status.

Because they’re not required to meet Nevada’s standard for achievement, local Catholic schools have more freedom with their curriculum.

Roybal-Benson declined to share the results of the school’s most recent standardized testing, saying it was intended for use only by school officials. But he said his students are working about a year ahead of their peers at district campuses.

In some areas, the gap is wider. The school’s first graders are writing research reports that cite three sources. That’s a task typically assigned to third graders in the Clark County School District, Roybal-Benson said.

At Bishop Gorman, students averaged about 1,100 last year on SAT college entrance exams, compared with the districtwide average of 986.

Bishop Gorman graduates about 98 percent of its students, compared with the district’s 60 percent average. The school doesn’t calculate a dropout rate. Its students don’t drop out, officials said; they transfer to other schools.

Among the 212 students in the class of 2008 were 27 Nevada High School Scholars, 19 recipients of athletic scholarships, two national Latin Award winners and two National Merit finalists.

Academics aside, for senior Zack Sanderson the fact that Bishop Gorman is, first and foremost, a Catholic campus enhances his experience.

Morning prayer at school is “a great way for me to commence the day,” he said. “We get a chance for reflection and to prepare for the day spiritually.”

Public school alternatives

Despite their strengths, Catholic school enrollment has sharply declined nationwide.

But experts say parochial schools continue to fill an important educational role that benefits the entire community.

When parents lose confidence in their local education system, parochial schools, along with other private and charter schools, can fill the gap, said John Convey, professor of education at Catholic University in Washington, D.C.

Parochial schools are often more popular in states where public schools struggle, he said. That has been the case in the nation’s capital, where the public school system has been in disarray for years.

The competition will force the public schools to improve, Convey said. “It’s going to make everyone try harder.”

In the past decade, the Clark County School District’s enrollment has jumped 53 percent — to 311,356 in September, from 203,777 in fall 1998.

As the district has struggled to accommodate about 12,000 new students a year and fight negative perceptions about performance, private schools have thrived, with several new campuses opening and older ones expanding.

Parochial schools, however, are not generally seen as a means of forcing public schools to improve, but rather as a supplement and opportunity for choice, according to experts.

“They hold some advantages over us — they have more selectivity, and typically when people are paying directly for their schooling they place a higher value on it,” said Rulffes, who attended a Catholic grade school.

A strong parochial school network, particularly one that serves poor and at-risk children, can also be a financial boon to the public system, saving taxpayers millions of dollars from the cost of educating these students.

The Thomas B. Fordham Institute, a nonprofit education policy think tank, estimated that the closure of more than 1,300 Catholic schools since 1990 has shifted to public schools $20 billion in costs to educate the former parochial students.

Because Nevada funds public schools on a per-pupil basis, there isn’t a direct cost saving to the Clark County School District for each student who opts to attend a parochial or private school. But in a district where overcrowded schools have been a critical concern, fewer students does save on capital expenses because fewer classroom seats are needed, Rulffes said.

During the decade that Southern Nevada’s parochial school system built just one school, the Clark County School District tapped a $3.5 billion, voter-approved bond measure to build more than 100 campuses.

The Phoenix experiment

Nationwide, about 5.2 million K-12 students were enrolled in Catholic schools in the early 1960s. Today, that number has dropped to 2.3 million.

The migration of families to the suburbs from cities, where the corner parish school was a community institution, is one reason.

Priest sex-abuse cases, which led to enormous financial settlements in some cities, are also “making it very difficult for a lot of these dioceses to support Catholic education the way they once did,” said Mike Petrilli, the Fordham Institute’s vice president for national programs and policy. “The church asks parents to pay more, they can’t, and the school closes. We see this as a death spiral.”

St. Louis, with a strong parochial school tradition, has dealt with the decline. Phoenix, a desert metropolis with similarities to Las Vegas, has bucked the trend.

In St. Louis, home to the nation’s seventh-largest Catholic school system, about 35 schools in the archdiocese have been closed or consolidated in the 14 years since George Henry was named superintendent. Enrollment stands at about 49,000 at 121 elementary schools and 29 high schools.

Henry acknowledged there has been a significant loss of students despite a parochial school tradition going back to 1818.

“We have history and tradition on our side,” Henry said. “Where you went to school and where your parents went to school is a big deal.”

Catholic schools in Las Vegas, with its transient population and relatively short history, might not have the generations of loyalty that St. Louis enjoys.

But the experience of Phoenix shows it’s possible for Catholic schools to flourish in a fast-growing western city. As parochial school enrollment has slipped nationwide, the student population of the Diocese of Phoenix has jumped 24 percent.

Like Las Vegas, Phoenix has for decades endured sprawling growth, attracting a similar mix of young families, Hispanics and retirees, many of them Catholics. The population of the metropolitan area is more than 4 million.

The Diocese of Phoenix counts 130,000 registered families, nearly double the 70,000 claimed by the Diocese of Las Vegas. But because it has continued to expand its education system, the Diocese of Phoenix has nearly four times more students, 22 more elementary schools and five more high schools than the Diocese of Las Vegas.

A capital campaign, launched in 1998, has added five elementary schools.

The growth of the Phoenix schools has been aided by a Catholic Tuition Organization, which this year provided $12.5 million in financial support to 6,500 students, just over 42 percent of the total enrollment.

The money comes from corporate and individual contributions. Arizona is one of a few states that offers a credit on personal and corporate income taxes for donations to “school tuition organizations,” nonprofit groups that support private school scholarships.

MaryBeth Mueller, superintendent of Catholic schools administration of the Diocese of Phoenix, said that city’s Catholic schools still can’t meet the demand.

Two of the newer elementary schools started small, and “could add another classroom per grade and fill them,” she said. “People are making huge sacrifices to have their children in Catholic schools. Folks are strapped, but they are willing to put the resources in.”

In Las Vegas, several parish schools, which charge from $2,500 to $4,300 a year in tuition, have waiting lists.

The diocese has bought land in recent years for future schools. But construction costs continue to be prohibitive, and a capital campaign would likely be needed to pay them.

It’s unlikely individual parishes would be willing or able to take on the burden of building a school without the support of the diocese.

The Bishop Gorman story

Some have begun calling Bishop Gorman’s new Summerlin campus “Bishop Gorgeous.”

From the blown-glass pendant lighting illuminating the atrium lobby to its classroom buildings named for donors, the $105 million campus, which opened in 2007 with capacity of 1,200 students, is spacious and warm.

(The district’s Legacy High School, built to accommodate 2,700 students, opened while Bishop Gorman was under construction at a cost of $75 million.)

There are state-of-the-art science classrooms and a performing arts theater. The gymnasium and athletic fields are worthy of student-athletes who routinely compete for regional and state championships. In the sunny cafeteria, students can choose from made-to-order sandwiches, sushi and other atypical school-lunch fare.

In one sense, the new Bishop Gorman, with an enrollment of about 1,100, a 25 percent increase from 1998, marks the beginning of Las Vegas Catholics’ efforts to reemphasize education.

When Bishop Joseph Pepe arrived in 2001, a committee of prominent alumni and community leaders was scouting possible locations and potential financial backers for a new Bishop Gorman campus to replace the then-47-year-old Maryland Parkway facility.

Pepe supported their effort with the hope it could raise the standard for Southern Nevada’s Catholic schools.

The fundraising campaign took several years, with community leaders and alumni signing on in support. In 2003, as the diocese closed escrow on the 35-acre site near the Las Vegas Beltway off Hualapai Way, the cost of the new campus was estimated at $35 million to $40 million.

About $25 million was expected to be raised through the capital campaign. But the committee quickly learned that building a high school, particularly one with high-tech features and elaborate design elements, would be significantly more expensive.

About half of the $105 million cost was covered by contributions, Pepe said. Another $16 million was raised with the sale of the old campus. The rest was paid by the diocese.

The lesson from that effort, Pepe said, is that the community will support Catholic school construction. At the same time, the diocese recognizes that because of the recession, costs could be a bigger hurdle for future schools.

Church leaders said the master plan they have begun working on will determine how the parochial school system can serve more students. It could lead to a strategic shift toward regional schools operated by the diocese, such as Bishop Gorman, rather than by individual parishes.

For example, a regional junior high school could allow the parish schools to operate as

K-5 campuses and free up classroom seats for popular kindergarten programs.

The master plan could also lead to the consolidation of existing campuses or closing of schools, officials said.

“Our plan is to start measuring the priorities of our parishes with the need for schools,” Pepe said. “Given the cost of construction and buying land, a regional school in a central location might make more sense, and allow us to serve more of the population.”

Convey, the Catholic University professor, said there’s no formula for how many schools a diocese needs to serve its members.

“The question is really about access,” Convey said. “Are the schools at capacity or could they take more students? Are there waiting lists?”

Pat Mulroy, general manager of the Southern Nevada Water Authority and a key fundraiser for the new Bishop Gorman, said there is “a desperate need” for additional classroom seats.

“There are children in the public school system who, if there had been space for them, would be in the Catholic school system,” Mulroy said. “The difficulty has been the explosion in population. We need more parishes, never mind schools.”

As the diocese drafts its future educational blueprint, money will be a factor at almost every level.

Pepe said he wants to make Catholic education more affordable. There are scholarships, but it might be time to start building a separate endowment specifically to support enrollment growth, he said.

Now that Bishop Gorman has settled into its new home, the time might be right to discuss scholarship endowments, Mulroy said.

Some Catholic educators fear the recession will hurt enrollment, as what was once a relatively modest tuition bill becomes a hardship for some families.

With Bishop Gorman’s move to Summerlin, keeping tuition affordable was always part of the plan, Mulroy said.

Tuition at the high school is $10,900 a year. Students whose families belong to a local parish pay $9,300. (By comparison, at the private Meadows School, tuition ranges from $14,990 to $19,950 depending on the grade level. The Alexander Dawson School in Summerlin charges $17,800 per year.)

In addition to the cost of constructing new schools, there is also the need to staff and operate the facilities.

Only a few of the teachers in the area’s Catholic schools are active or retired clergy, or members of a religious order. As one educator noted, it was easier to run parochial schools 40 years ago because “the nuns worked for free.”

Like dioceses across the country, Las Vegas has struggled to find enough priests to run its parishes, never mind teachers for its schools.

Nationally, 95 percent of Catholic school staff are lay teachers.

Pay for Catholic school teachers in Las Vegas is 90 percent of the Clark County School District pay scale. Church officials said they are able to find enough qualified staff to run the campuses.

Tito Tiberti, whose family’s construction company built the new Bishop Gorman campus and is an alumnus, said there is enthusiasm for expanding Catholic schools here. The recession, however, makes accomplishing that less than certain.

“What my thoughts might have been in August are different today,” Tiberti said. “I can’t tell you where we’re going in this town. People might say they want to support new schools, but they might not have the wherewithal to commit to that.”

By not adding more schools over the past 10 years — a decade during which Southern Nevada saw an unprecedented economic boom — the diocese might have missed a prime opportunity to expand as disposable income was plentiful and home values were high.

Or perhaps the Clark County School District’s grim fiscal forecast — $130 million in budget cuts with another $120 million looming — makes it the right time to push for educational alternatives.

Tiberti said the economic uncertainty validates Pepe’s call for a long-range plan.

“If you believe in parochial education like I do, you have to do a master plan,” Tiberti said. “The key is that it needs to be flexible. When you’re up against such tremendous forces like we are right now, it’s not realistic to come up with something rigid. But that doesn’t mean you don’t plan for the future.”

Influx of faithful

The 7 p.m. Sunday Mass at St. Bridget was still an hour away, but the parking lot and the pews at the Catholic church near downtown Las Vegas were nearing capacity.

Dozing babies stretched out on blankets, guarded by grandparents. Giggling girls in jeans and young boys in neatly pressed shirts wandered the vestibule.

By the time the Spanish-language service began and Father Jesse Cortes offered his invocation, nearly 700 people had joined him in worship.

It’s a marked change from years past, when if 80 people showed up for Sunday Mass at the original St. Bridget chapel, it was considered a crowd.

A few years ago the Spanish-language Mass was added in a nod to the changing demographics in the surrounding neighborhood of small tract houses and modest apartments. Attendance quickly swelled to standing room-only crowds, with hundreds often turned away.

In February, the spacious new St. Bridget was dedicated. Today, the church offers two Spanish-language Masses each Sunday, as well as a Filipino service.

Attendance at each Mass regularly tops 500.

In many ways, St. Bridget represents the future of the Diocese of Las Vegas, where Hispanics make up nearly a third of active parishioners and the fastest-growing segment of its membership.

When the possibility of a new school is raised, Cortes says it’s “beyond our capacity.” More than a school, the parish needs a social hall, which could provide an additional source of revenue, Cortes said.

“We still have to pay for the church,” he said.

In the vestibule of St. Bridget, volunteers had set up a table of raffle prizes — a decorative jug, a hand-painted guitar and a home theater system — with the proceeds going to the church’s building fund.

Maria de Jesus Diaz, a St. Bridget parishioner for 12 years, said she believes many more people would opt for parochial education if not for the cost. In these tough economic times, even a raffle ticket can be a hard sell.

“Our families love their church and want to support it,” she said. “But $350 per month for one child’s tuition, how can they can afford that?”

Church officials say there’s no question the diocese needs more schools. But, as the experience at St. Bridget illustrates, it also needs more parishes. And both require money.

It’s a familiar situation for the diocese.

“In the seven years I’ve been here there’s always been a press for more schools,” Bishop Pepe said. “In 2001, there were 450,000 people who identified themselves as Catholic. Now it’s 700,000. With that kind of exponential growth, our first task was to identify areas, buy property and establish parish centers. Once you build the worshipping community, then you begin to get the requests for schools.”

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy