Wednesday, Feb. 11, 2009 | 2 a.m.

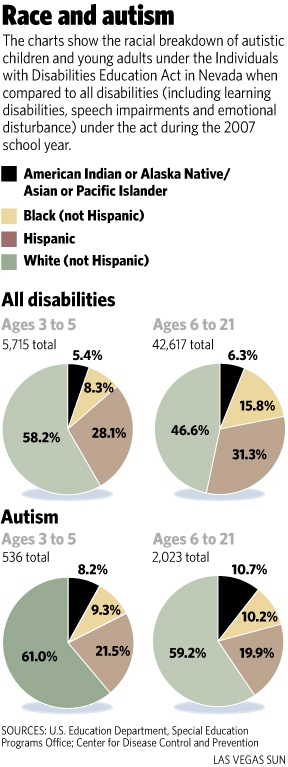

RACE AND AUTISM: The charts show the racial breakdown for autistic children and young adults under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act in Nevada when compared to all disabilities (including learning disabilities, speech impairments and emotional disturbance) under the act during the 2007 school year.

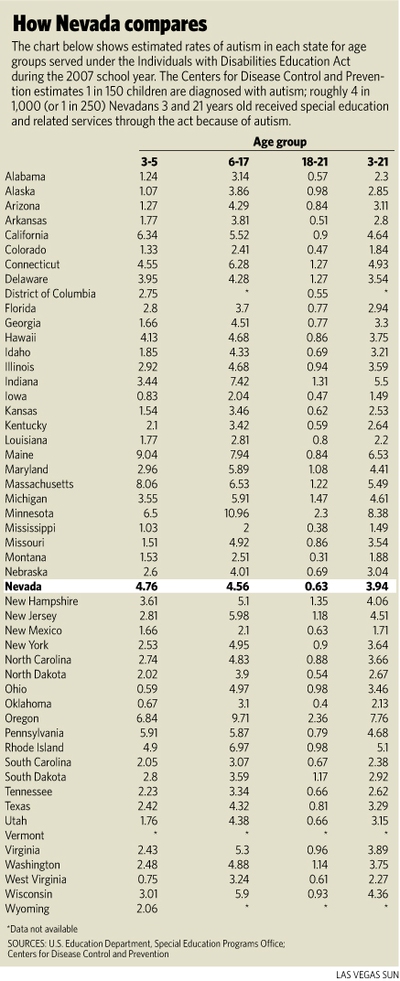

HOW NEVADA COMPARES: The chart shows estimated rates of autism in each state for age groups served under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act during the 2007 school year. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates 1 in 150 children are diagnosed with autism; roughly 4 in 1,000 (or 1 in 250) Nevadans 3 to 21 years old received special education and related services through the act because of autism.

Sun coverage

Democrats in the state Assembly will unveil legislation this week to force insurance companies to provide coverage for the treatment of autism.

The measure stands a strong chance of passing, given that it has the support of the leaders of the Senate and the Assembly.

The idea has become a contentious issue nationwide, as autism diagnosis has increased markedly in recent decades. Autism, a developmental disorder often impairing socialization, is now diagnosed in 1 out of every 150 children, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The cost of effective treatment can reach $24,000 to $40,000 per year per child, with additional costs resulting from the various medical conditions that usually accompany autism, according to Ralph Toddre, founder of the Autism Coalition of Nevada, who also sits on the Nevada Commission on Autism Spectrum Disorders.

Insurance companies have traditionally declined to pay for treatment, which usually involves intensive speech and occupational therapy. They assert that the care is not strictly medical even though it arises from a medical condition.

But autism treatment mandates are sweeping the country, in Democratic states such as Pennsylvania as well as in Republican states such as Arizona and Louisiana. The New Mexico Senate approved a measure just this week.

The bill poses an important policy question: Who pays for Nevada’s neediest and most vulnerable?

Assemblyman James Ohrenschall, D-Las Vegas, said the insurance industry, which he called a “regulated monopoly,” is often guided by “perverse incentives” not to cover various conditions. He said it is time for government intervention.

On the other hand, mandates for coverage invariably increase the price of insurance premiums, which critics say is a perilous policy as the recession deepens and employers consider dropping health benefits to cut costs. According to an actuarial study completed by the Council for Affordable Health Insurance, the mandate would add 1 percent or less to premiums, though the estimate only included individual and small group rates.

“Forcing people to buy things through mandated coverage they don’t need and may never use has greatly driven up costs across the country,” said Joel White, executive director of the Coalition for Affordable Health Coverage in Washington.

White said there’s no dispute that incidence of autism has reached crisis proportions and that families with autistic children need significant help, though he said it should be through other means, specifically government programs that would insure the essentially uninsurable.

Edmund F. Haislmaier, a health care policy analyst with the conservative Heritage Foundation, largely agreed, and said treatment should be paid for by Medicaid or school districts. He said the mandate on insurance companies is essentially a tax increase on those who pay premiums.

The insurance industry also notes the mandates would not apply to as many as 40 percent of plans in Nevada because they fall outside the purview of state regulation and thus can ignore the mandates. These include plans covering some government workers, but also collective bargaining trusts, such as the Culinary Union’s health plan, which is regulated by the Labor Department through the Employee Retirement Income Security Act. Bobbette Bond, a lobbyist for the Culinary health fund, said she’s aware of no coverage mandated by Nevada law that Culinary doesn’t also provide.

The Culinary may need to consider adding autism treatment if it wants to continue to match state mandates, because it seems highly possible the bill will become law.

Speaker Barbara Buckley, D-Las Vegas, was Ohrenschall’s first co-signer, and Senate Majority Leader Steven Horsford, D-Las Vegas, is also supportive. A spokesman for Gov. Jim Gibbons didn’t respond to a request for comment.

Buckley said insurance lobbyists have told her they understand this is a policy goal of the Democratic-controlled Legislature and are willing to assist in the crafting of an eventual law.

Ohrenschall has also won the support of several Assembly Republicans, including a key advocate, Assemblywoman Melissa Woodbury, R-Henderson, who teaches autistic children in the Clark County School District.

For their proponents, these laws offer a win-win: They gather support from an energized and well-organized constituency, and they force the insurance industry to pay for treatment that might otherwise fall to the state or school districts, and, in the case of the Silver State, Nevada Early Intervention Services.

If neither the insurance industry nor the government pays, the burden is left with families with autistic children.

Toddre, who has two autistic children, said, “The financial burden is unbelievable to try to give your child a decent future and a decent life.”

No matter who pays, data suggest the upfront treatment is cost-effective.

Autism is referred to by clinicians as Autism Spectrum Disorders, which refers to the wide range of symptoms and functionality among those born with it. The shared symptoms include problems with social interaction, verbal and nonverbal communication, and repetitive behaviors or interests, according to the National Institute of Mental Health.

Without intensive treatment, autistic children will more than likely become wards of the state when they reach adult age.

Woodbury cited research showing 47 percent of children who receive early intervention and at least 30 hours per week of treatment lead independent lives as adults.

Of those who do not, 90 percent need a lifetime of expensive custodial care.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy