Cabdriver Tulay Koseoglu is en route last week to McCarran airport. She says with fewer tourists visiting Las Vegas, days when she makes $60 in a 12-hour shift are becoming more frequent.

Sunday, Feb. 8, 2009 | 2 a.m.

Enlargeable Graphic

A Primer on Minimum Wage

Nevada has a two-tiered minimum wage: Employers who provide workers with qualifying health insurance coverage must pay $5.85 an hour; employers who don’t must pay $6.85 per hour.

Many employers pay the higher amount because funding health plans is much more expensive than paying workers an extra dollar per hour. To qualify for the lower wage, health insurance premiums must be less than 10 percent of a worker’s gross taxable income.

Employers can’t count tips toward the minimum wage. And workers covered by a union contract can be exempted but only if the collective bargaining agreement waives minimum wage claim rights.

Taxi drivers were exempt from minimum wage until November 2006, when voters amended the Nevada Constitution to raise and broaden the minimum wage standard. Some cab companies think they are still exempt, or that tips should be included in the calculation of minimum wage.

Under state law, employees must receive at least minimum wage for every hour worked – as long as they are paid by the hour. But people who are paid a salary, for piecework or in any other way besides hourly have a different standard for how minimum wage is calculated that is based on the pay period. This includes cabdrivers, who are not paid an hourly rate but according to how many rides they receive, according to Nevada’s Labor Commissioner. Cab company owners must pay at least minimum wage as determined by a driver’s total pay over a given pay period divided by the hours worked over that pay period. Drivers paid biweekly who had several good days followed by one bad day might not actually earn minimum wage on that particular day because their minimum wage rate is averaged over a two-week period, for example.

Each year, the Labor Commissioner calculates Nevada’s minimum wage based on the Consumer Price Index. Increases, which can be no greater than 3 percent per year, are calculated from a base rate of $5.15 per hour — the rate at the time of the constitutional amendment. New rates take effect July 1.

The Nevada Labor commissioner regulates state minimum wage standards, but the minimum wage law allows employees to pursue lawsuits in state and federal court. Employers are required to follow state and federal minimum wage laws, allowing workers to pursue wage claims under federal law against employers who pay less than $6.55 per hour.

The Nevada Constitution states that employers “shall not discharge, reduce the compensation of or otherwise discriminate against any employee for using any civil remedies to enforce” the minimum wage law.

So How Much Do Cab Drivers Really Make? It Depends

Cab drivers pocket less than half of the money they earn from rides on a given day, splitting the revenue with their employers and paying for things such as gasoline and per-trip charges that fund the Nevada Taxicab Authority, which regulates the cab industry. Most companies receive 55 percent to 65 percent of drivers' daily bookings. Drivers keep their own tips and must declare about 25 percent of their earnings to the IRS as tip income.

Cab companies generally blame drivers' job skills, rather than the economy, for poor performance. Companies interviewed by the Sun say they pay at least minimum wage, even for their lowest performers. Some drivers are better at their jobs than others and should be judged relative to their peers, they add. Drivers say unscrupulous "long-haulers" – drivers who take a longer route to get to a given destination – drive up those averages, pressuring honest drivers to do the same. Cab companies such as Lucky Cab say they fire long-haulers, who are revealed by tripsheet activity showing inflated fares for given routes.

Actual tripsheets from Lucky Cab drivers on a single day in January show a wide range in earnings. Lucky Cab owner Jason Awad says higher-earning drivers don't linger long at any given location, moving around frequently in search of rides, while low performers may wait in a line of cabs for up to an hour or end their shifts early. Some drivers use a system of numbers to indicate hotels and other locations.

Beyond the Sun

On a recent weekday, Tulay Koseoglu sat in her taxi at the Riviera for more than an hour waiting for a tourist to exit the property.

“This just kills me,” said Koseoglu, who became a cabdriver three years ago to escape her “ordinary office job.”

On bad days, which are becoming more frequent, Koseoglu might take home $60 after a 12-hour shift.

Momentarily, there was good news: She scored a ride for two passengers to the airport, from which she might pocket another $10, including a tip. This afternoon ride would be her 11th of the day. She had a couple of hours to scramble for more rides before her shift ended.

Her friendly chatter is tinged with desperation.

While her peers pass the time in cab lines reading newspapers, doing crosswords or playing miniature video games, Koseoglu can’t relax. Her mind is racing with worry. In recent months, drivers say, cab companies — which pocket more than half the money drivers collect from passengers — have fired hundreds of drivers for below-average bookings.

“I’m thinking about bills,” she said. “I’ve got a 7-year-old.”

Like sparse crowds inside casinos and on Strip sidewalks, empty cab stands have become a symbol of the epic tourism downturn in Las Vegas. On any given day, cabs gather at hotel entrances in lines so long they clog off-ramps and roadways.

At McCarran International Airport, a former gold mine for taxis during the boom years, more than a hundred cabs line up on weekdays. With airport traffic down 7 percent and visitor volume down 4 percent last year through November — some drivers say they are waiting 45 minutes or more for their turn at the front of the line.

Slow business has led to layoffs and fewer hours for casino and hotel workers, but the picture looks bleaker for taxi drivers, who aren’t paid a base wage like most workers but instead must depend on their ability to get rides.

These days, some cab drivers who used to make more than $30,000 a year are earning less than $20,000. Drivers who got 25 to 30 rides per shift are now lucky to get 20.

•••

Drivers are supposed to have a safety net.

In November 2006, voters amended the state Constitution to raise Nevada’s minimum wage, which now starts at $5.85 per hour. That amendment applied the minimum wage to all Nevada employees, removing an exemption for taxi drivers.

Before the recession, the minimum wage standard was moot — all but the worst performers were assured a paycheck higher than minimum wage.

These days, at least one major cab company has acknowledged that some drivers aren’t booking enough rides to earn minimum wage, forcing the company to supplement those drivers’ paychecks as company revenue is plummeting.

Not all companies are going quietly. Some cab companies think drivers should still be exempt from the minimum wage and are pressing Nevada’s labor commissioner to take their side.

Lucky Cab owner Jason Awad called the position taken by some of his competitors “disturbing” and said companies have a moral obligation to pay minimum wage. “Drivers must be able to support themselves and their families,” he said.

Awad says he hasn’t laid off hardworking drivers in recent months who are booking fewer rides with the understanding that business is slow for everyone. Because drivers split their take with cab companies, both parties have the same incentive to earn as much as they can during tough times, he said.

“These are unprecedented times but we’re in this together, and we need to help each other get through this.”

That said, Awad noted that all drivers should be able to make minimum wage “and if they are not they should be looking for another job.”

Bill Shranko, chief operating officer of Yellow Checker Star, said his company hasn’t laid off any drivers because of the economy.

“Some companies are taking a very strict approach to it,” Shranko said. “As a company, we are taking a very liberal approach during these hard times.”

Business hasn’t been so bad that minimum wage has been an issue, he said.

It’s unclear whether drivers who have been fired since business slowed were earning below minimum wage. Some drivers claim that several fall into that category based upon dismal bookings of well under $200 per day and drivers pocketing 40 percent of that. (During December, one of the worst months on record, drivers booked an average $192 per shift.)

Driver Bill Talley says he was fired from his job at a Frias Transportation-owned cab company in September after 15 years of service.

With the slow economy, Talley said, some drivers have inflated their bookings through an illegal practice called long-hauling, which involves taking passengers on longer routes than necessary. Although long-hauling has always been a problem, some Las Vegas taxi drivers say it’s getting worse now that drivers are afraid they will be fired for low bookings.

“It’s a money game, and drivers have to steal to make it work,” said Talley, who hasn’t been able to get a job driving a cab elsewhere. “I didn’t want to get into that game. But nobody wants to hire a guy who’s been fired for low book. They don’t make as much money as the hustlers.”

Drivers caught long-hauling by Nevada Taxicab Authority police are fined, but drivers say the extra cash — especially if they think their jobs are on the line — is worth the minimal risk of getting caught.

Frias Chief Executive Mark James said his company pays at least minimum wage and is supplementing drivers who are earning less than that in rides to bring them up to that standard.

“The lion’s share of the time, our drivers are way beyond minimum wage,” he said. “If they have a low book, for whatever reason ... we make up the difference.”

•••

Ask a cabdriver whether he or she makes minimum wage and you will more likely than not get a blank look. Many drivers don’t know the law or have never calculated whether their paychecks come out to the minimum wage.

Meanwhile, regulators say Nevada’s two-tier minimum wage law is difficult for employees and employers to understand.

These days, word is spreading and some drivers are fighting for minimum wage. Some drivers have pushed for a wide-ranging investigation or a class action complaint.

But Nevada Labor Commissioner Michael Tanchek says his small staff, handling more than 6,000 pending wage claims, is hamstrung by a lack of resources.

He investigates claims on a case-by-case basis. Because a significant number turn out to be bogus, Tanchek says the initial burden is placed on employees to prove what they are owed.

Some drivers are reluctant to file complaints, saying the process gives employers plenty of time and opportunity to fire low-performing drivers despite state law protecting workers from retaliation.

“I have pretty much stopped telling drivers to file complaints with the labor commissioner because it was like telling them to walk into a buzz saw,” said Randell Hynes, a cabdriver who was fired from Nellis Cab last year.

One group of drivers has lost the battle for minimum wage.

The state’s minimum wage law includes an exemption for union-represented employees with collective bargaining agreements that specifically waive workers’ rights to complain about wage violations. But the drivers’ employer, Frias, together with the United Steelworkers Local 711A union, signed a waiver last year preventing the drivers from getting the money they were owed.

The waiver forced the labor commissioner to revoke a complaint against Frias on behalf of a group of drivers who weren’t earning minimum wage.

That a union would agree to a lower standard is surprising, Tanchek said.

“To be honest, I never thought I’d see something like this,” he said. “I can see why the drivers would be unhappy.”

Gene Brady, Frias unit president for the local Steelworkers union, said the union signed away rights to minimum wage in 2007 in exchange for a union contract at Virgin Valley Cabs, one of the five cab companies owned by Frias.

“At the time, with the economy as strong as it was, nobody felt this would be an issue, or that people would want to work for minimum wage,” Brady said.

•••

During the boom years in Las Vegas, Hynes recalls, he made more than $40,000 a year driving a cab — about what he used to make building Web sites. By the time he complained to the Taxicab Authority last year about not earning minimum wage, he estimates he was making less than $20,000 a year.

He says he was fired by Nellis for speaking at a Taxicab Authority meeting but was rehired when he mentioned an anti-retaliation section of state law.

Hynes ended up quitting when he couldn’t make ends meet on his earnings.

Nellis representatives declined to comment.

Cab companies generally blame drivers’ job skills, rather than the economy, for poor performance.

Some companies say drivers are given more training if their earnings are more than 10 percent below the average for a given day or shift.

“We have some guys who take a lot of breaks, or maybe they were not feeling well that day, or their child was sick,” said Awad, the Lucky Cab owner. “It’s like any business in any industry — some employees don’t work as hard as others ... When somebody books $400, the average is $250 and someone comes in with $100, there’s a problem.”

High-earning drivers are in constant motion, rarely waiting in a cab line for more than 30 minutes before seeking riders elsewhere, he said. Trip sheets for low-booking drivers reveal long waits at hotels or shifts drivers ended early, he added.

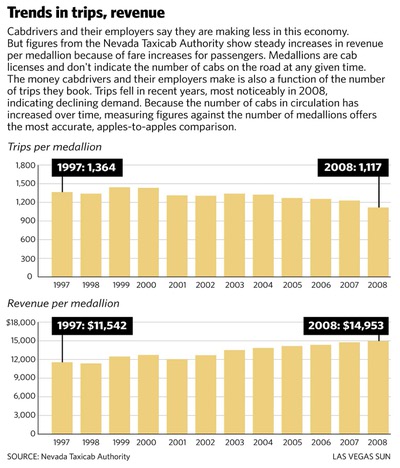

Taxicab Authority Administrator Gordon Walker says it’s unlikely drivers aren’t earning minimum wage, given the agency’s own figures. According to audited figures collected from the 16 cab companies, drivers booked an average of $250.49 in revenue per shift in 2008.

Hynes, who is now seeking employment as a computer programmer, said drivers’ efforts to fight for minimum wage reflect a change in the industry or tougher times.

It used to be that low wages were an accepted hazard of the cab business during slow times, he said.

“If you didn’t get as many rides, you just took your lumps,” he said. “Now, more drivers are realizing that they are entitled to a fair wage.”

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy