Commissioner Susan Brager says with Clark County facing possible layoffs, longevity pay “is something we should be investigating.”

Thursday, Dec. 10, 2009 | 2 a.m.

Related Document

- Report shows Clark County employees who earn longevity pay, including their total pay, overtime and other allowances.

- Excel spreadsheet

Reader poll

Steve Sisolak

Sun Archives

Clark County employees have some of the best jobs in the state in terms of pay and benefits. And yet on top of their relatively high base pay and other raises, thousands get paid annual bonuses as an incentive to remain on the county’s payroll.

The validity of the county’s “longevity pay” has been questionable for years, but in these days of budget slashing and layoffs, it is starting to look ludicrous to some county commissioners.

The reason: In the fiscal year that ended June 30, the longevity pay and its associated costs totaled $44 million.

Even one of the least outspoken commissioners, Susan Brager, said this week that with commissioners trying to stave off cuts in public service and facing “the prospect now of laying off people,” longevity pay “is something we should be investigating.”

This year has arguably been among the toughest in the county’s 100-year history. But next fiscal year might be even worse. The county is projecting a tax revenue shortfall of about $120 million. With an average yearly salary-and-benefits package of about $90,000 per employee, it would have to lay off about 1,400 people to make up that shortfall.

Getting rid of longevity pay would do much to cut that deficit.

Employees in fiscal 2009 received direct longevity pay bonuses totaling $34.6 million — $9.1 million to University Medical Center employees and $25.5 million to other county employees.

But longevity pay costs the county more than just what shows up in the regular pay portion of employees’ checks because it forces increased payments to those employees’ retirement funds too. Last year, that amounted to about $7.5 million. It also ratchets up overtime payments, by $2 million last year.

Tax revenue is used to cover most, but not all of the bills for longevity pay. All payments to retirement accounts are made by taxpayers. But of the $25.5 million spent on the direct bonus money, $8.5 million comes from fees the county charges for airport use, inspections and other services. Also, UMC’s expenses, including salaries, are supposed to be covered by fees for services. The county, however, kicks in tens of millions each year to cover its budget deficits.

Commissioners, who are scrutinizing contracts more carefully and seeking ways to save money to reduce the number of layoffs, take little consolation in fees covering some of the longevity pay tab.

“There are so many of these things — cost-of-living raises, step increase, merit raises, longevity bonuses, whatever you want to call them, you have to start asking: For what?” Commissioner Steve Sisolak said. “I talk to people in the private sector who are just happy to keep their jobs, and we’re giving all this money away. We have got to put a tighter rein on this. The county has to get a handle on it.”

No cap on longevity pay

That’s just what Thom Reilly tried to do when he was county manager in the early 2000s. Now a professor of social work at San Diego State University, Reilly has written academic papers about public employee benefits.

“The argument used to be, ‘Well, we can’t pay you overtime, but if you stay with us, we have this longevity pay,’ ” Reilly said. “Now, of course, the public sector outpaces the private even in wages. Then they have these benefits and it further exacerbates the difference with private sector.”

Las Vegas also makes longevity payments to some of its employees. Unlike the county, though, the city’s policy differentiates between categories of employees, differs by years of required employment, does not include elected officials and is capped at 10 percent of base pay.

Clark County has no longevity pay cap, and elected officials — including commissioners — get 2 percent of their base pay added on each year after four years in office. Commissioners cannot receive longevity pay greater than 20 percent of their base pay.

“Commissioners should not be getting longevity pay at all,” Sisolak said. “Why would we?”

Reilly said he eliminated longevity pay for new management hires after June 2002 and replaced it with performance-based incentives. It forced some county employees to do some fast maneuvering.

“That’s why the (county’s lawyers) unionized,” Reilly said, chuckling.

Rank-and-file employees still get the perk, however. The county's employee contract says that employees working as of Oct. 15, 1991, were eligible for longevity pay after five years of employment. After that date, employees had to work eight years to become eligible. Longevity pay is calculated at the rate of 0.57 percent per year, then multiplied by the number of years of employment.

A county employee making $100,000 after eight years would get $4,560 extra in her ninth year.

By the numbers

The Las Vegas Sun obtained the names and amounts of longevity payments to county employees through an open records request. County staff did not provide the figures for UMC employees in time for this story, however.

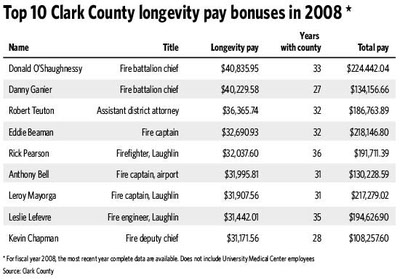

Not counting UMC workers, 3,533 county employees received longevity pay in fiscal 2009, which ended June 30. The median payment was $5,474. The greatest payment went to Donald O’Shaughnessy, a Clark County Fire Department battalion chief employed since February 1976. In fiscal 2008 his longevity pay totaled $40,835.95. He also received overtime payments of $61,314 bringing his total pay that year to $224,442. The next highest was also a Fire Department employee, Danny Ganier, who received $40,229.58 in longevity pay; his pay that year totaled $134,156.66. Nine of the top 10 longevity pay recipients worked in the Fire Department. In just one year, those 10 people took home a total of $340,770 in longevity pay.

Those bonuses alone are close to the median and average salaries in Clark County that year. The American Community Survey reported that the median household income in Clark County was $59,696. The Labor Department reported the average private sector salary was $42,000.

Longevity pay in the private sector, Reilly noted, is almost unheard of.

Above average pay

On the other hand, the relatively high pay of local government employees in Nevada is well known. In June 2008 a study commissioned by the Las Vegas Chamber of Commerce reported Nevada’s local government workers (of which Clark County’s constitute a lion’s share) are paid 31 percent more than the national average for local government workers. (It also found, however, that Nevada had the nation’s fewest number of government employees per capita.) Another chamber study last summer found that in Nevada, the average government employee was paid 28 percent more than the average private-sector employee in a similar job.

Sisolak said firefighters keep showing up at the top of the county’s highest paid lists because they have “had their way” with the county since the 9/11 attacks.

“They were viewed as untouchable, so no one (in county administration) even contemplated saying no to anything they asked for,” said Sisolak, who was elected in November 2008.

But service employees, many of whom work for UMC, also take a big chunk of those longevity payments.

Reilly remembers talking informally in 2006 to representatives of the Service Employees International Union, which today represents 9,500 county workers, about slowly weaning them off longevity pay. He chuckles in recalling how union officials said they would rather see layoffs instead of pay decreases.

“They said it was going to be a holy war,” he added.

A union representative did not return a call for comment.

Times are much different, and much worse economically than just three years ago. Elected officials are beginning to realize that local government employees have been largely unaffected by the recession, Reilly said. Public employees are protected by longevity pay and other “defined benefits” guaranteed in many union contracts.

In Clark County, Reilly said of unions, “the only concessions that have been made are to reduce the amount of their salary increases. Consider that in light of the wage cuts that people are experiencing elsewhere.”

In the long term, Reilly said, commissioners need the courage to push the Legislature to pass laws to allow collective bargaining on anything except wages. He also recommends that Nevada’s laws be changed to open bargaining sessions to the public.

In the short term, negotiations with the county firefighters union begin early next year. The county agreed not to touch longevity pay for service employees union members until 2011 after the union made concessions in early 2009.

Clark County’s commissioners are all Democrats, the party that traditionally supports unions, but Sisolak said the county will have to make a case and, if needed, take a stand at those negotiations “because this is just getting ridiculous.”

Sun reporter Alex Richards contributed to this story.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy