Friday, Aug. 14, 2009 | 2 a.m.

Sun Coverage

Beyond the Sun

The start of Metro’s five-year robbery research and prevention project was, at least on the surface, pretty unremarkable: About 20 convenience store owners and employees were sitting in a room for two hours with police specialists, listening to a lecture.

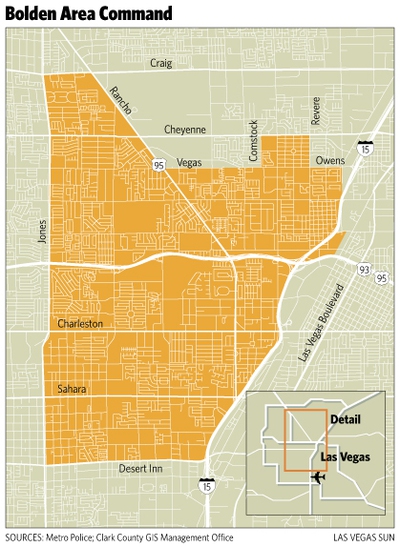

The topics covered — adequate lighting, unobstructed windows, keeping less cash in the register — must have likewise seemed pretty flimsy, at least when it comes to preventing business robberies, which happen almost three times a week to fellow convenience store employees in Metro’s Bolden Area Command, in the west-central portion of the valley.

But if previous studies are any indication, writing off simple storefront changes and meetings with police is a mistake. The same researchers helping Metro run the Crime Free Business pilot program have seen it work exceptionally well in other cities — dropping small business robbery rates by 41 percent in the space of a year.

Replicate this statistic in Las Vegas and it will underscore what cops such as Bolden Area Lt. W. Graham have long known: Robbery is a problem police can’t arrest away.

“If we’re going to stop robberies, I think we need to do it as a community,” Graham said.

When academics from University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill announced they were helping police departments launch Crime Free Business programs for a study, Graham put in Metro’s application. The department was one of three chosen. Metro was picked specifically for the density of its jurisdiction and its high crime rate, UNC researcher Carri Casteel said.

For the next five years, with a $24,000 federal grant, Metro will recruit Bolden Area businesses to join the pilot program, teaching those that enroll the strategies Casteel and colleagues have found reduce robberies.

In turn, Metro will send data back to researchers who are interested not in crime reduction (they know it’s possible), but in participation — what it takes to get business owners interested, what police departments need to do to make these programs work.

The ultimate goal is to develop a Crime Free Business model that can be employed at any department in the country, Casteel said.

Graham’s immediate goal is to get businesses on board. But asking small store owners and employees to attend after-work lectures, let alone commit to a long-term program, is a tough sell. When Casteel and colleagues set up a similar program in Los Angeles in 2001, they asked hundreds of small businesses to participate. Only a quarter followed through. Those who did saw that dramatic 41 percent drop in robberies. Those that didn’t saw nearly the opposite: A 43 percent increase in violent crimes.

Part of the problem was business owners had a hard time believing inexpensive changes — not gigantic surveillance systems or more security guards — could make a profound difference, Casteel said. People who participate in Metro’s pilot program are going to be instructed, in part, to de-clutter their windows, lock back doors, post placards advertising participation in the Crime Free program and keep most of the cash on hand in safes employees can’t access: Deterrents that send would-be robbers in search of softer targets.

With guidance from researchers, Metro will try different methods to drum up business participation. To this end, most of the grant money will be put toward advertising the program and printing educational materials in English and Spanish, Graham said. Eventually he hopes to involve not just individual mom-and-pop stores, but larger retail associations and community groups — people who can send a collective message to criminals that robberies aren’t going to be tolerated.

“We’re going to roll it out in phases, almost like a ripple effect in a pond,” he said. “That’s how I’m seeing it right now.”

Nationwide, a number of community-based crime prevention programs have gotten considerable attention because of studies indicating they work, regardless of the targeted crime: gangs, drugs, blight, robberies. The unifying idea behind these programs is that proactive policing, bringing citizens and civic groups into the crime-fighting picture, does more on the preventive front end than police can do alone on the back end, making arrests. A 2007 Cincinnati program, the subject of a lengthy profile in the June issue of The New Yorker, targeted gang violence with help from clergy and civic groups and yielded a 50 percent drop in gang homicides.

Closer to home, a Metro program that aims to use community partnerships to reduce gun violence in West Las Vegas led to a 37 percent drop in gun calls, according to UNLV researchers who released a study on the program last year.

These nontraditional crime prevention programs force police and businesses to reexamine how they work internally and with one another.

The police department in Oxnard, Calif., was the first to launch a Crime Free Business program for the UNC study last year. Getting the program off the ground meant building relationships with business owners, which can be difficult if there’s a perception police haven’t helped enough in the past, Oxnard Detective Martin Ennis said.

Today, 25 businesses are full-time members of the Oxnard program, and although it’s too early to say whether it has resulted in a decrease in robberies or crimes in the stores, Ennis is confident that improved relationships between police and business owners have had positive effects. In one case, detectives worked with a store owner to string together a series of isolated crimes into a larger theft arrest, building a big case over time and reducing the store’s monthly losses by thousands of dollars, Ennis said.

Still, a recent program seminar went almost totally unattended, he said. Why? That’s exactly what the UNC researchers want to know.

Ryan Haddrill, a regional loss prevention manager for 21 Las Vegas CVS pharmacies, attended the Metro seminar with three of his store managers. He instructs employees on safeguarding their stores all the time, but figured if they heard it from Metro directly, “It might have a little bit more impact.”

“I think partnership with police in general will go a long way,” Haddrill said.

Casteel suspects that partnership might be critical.

“A program like this probably can’t be sustained by a police department alone,” she said. “It’s really going to take a community coalition.”

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy