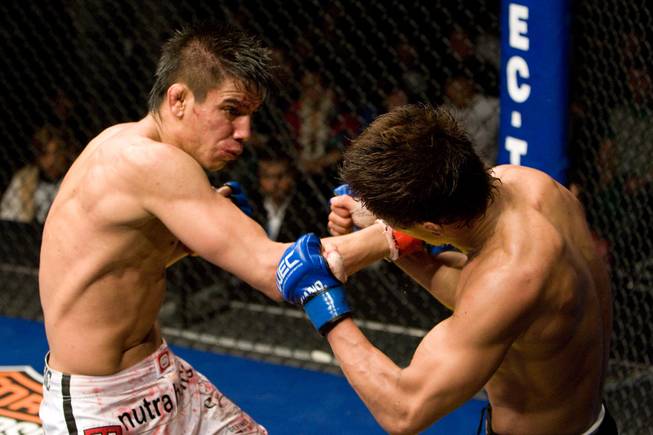

Courtesy WEC

WEC bantamweight champ Miguel Torres, left, defeated Takeya Mizugaki by unanimous decision at WEC 40 in April. Torres takes on Brian Bowles at WEC 42 on Aug. 9 at the Hard Rock

Wednesday, Aug. 5, 2009 | 8 a.m.

Arnulfo Torres was 18-years-old when he illegally crossed the United States border into Texas from Mexico. Torres quickly migrated north to an area in Chicago with a heavy illegal Mexican population, and found a job working labor.

Eventually he and his wife, Elisa, gave birth to three children, including a son they named Miguel.

Although Torres couldn't spend much time with his son because he was working two jobs to support his family, he made it a priority to play soccer and talk with Miguel during every free moment.

Somewhere in the middle of those father/son moments, one of his instructions stuck with the young boy.

"My dad told me at a very young age that he came to this country so that I could have a better life," Miguel said. "He was sacrificing his time, not going out and enjoying himself, because he wanted me to have the opportunity to do something with my life."

There are a lot of reasons why Miguel Torres is the defending WEC bantamweight champion and a top candidate for the distinction of the best pound-for-pound fighter in the world, but there's little doubt that it started with the desire to honor his father's sacrifices.

If there was ever a hard road to the WEC, it was the one traveled by Torres.

At the age of 17, when mixed martial arts was still illegal in the state of Illinois, Torres began his fighting career.

With no organized tournaments available at the time, fighters' only opportunities for competition were fairly primitive. The few that were involved in the MMA scene from the very beginning usually set up matches at their own residences.

"A couple times a fought in garages with no mats and the rules were you couldn't slam a guy because it was concrete," Torres said. "So, a lot of times we would fight in backyards so we could be on grass."

One year the owner of a Chicago bar realized that there was a profit to be made through alcohol and ticket sales to the growing MMA community. Torres was one of a group of fighters recruited to compete in loosely organized events where they were paid very little, if anything at all.

"There was a ring set up and it was the most decrepit boxing ring I've ever seen in my life," remembers Torres. "I'm not just talking blood stains, there were spit stains - guys would throw up because they weren't in shape and exhausted. Disgusting things were on that mat that you just don't clean up."

In addition to few competitions, training in Chicago was basically non-existant.

Torres taught himself MMA by stepping up to fight anyone that would challenge him, including opponents that were literally twice his size. Although he finally met Carlson Gracie Sr. at the age of 21, Torres' style was already set by then and he allowed Gracie to merely tweak some of his techniques.

"A lot of people don't understand that I didn't come from a jiu-jitsu background, I didn't come from being a boxer," Torres said. "My fight game was always geared towards MMA as a whole. When I learned kickboxing I wasn't learning it for tournaments, I was learning it to become a better fighter."

Torres' first experience with a 'gym' came when he and seven other fighters started to train in a garage. An aunt of one of the other fighters eventually lent them a key to the local parks and recreation center where they would hang a bag from the basketball rim and lie mats on the floor.

As time went on though, the other seven members of Torres' group began to stop coming because they couldn't compete with him anymore. The students that they had picked up along the way stayed to train with Torres.

"The other guys were coaches of a specific art, they wanted to be coaches they didn't want to fight," Torres said. "I was the experiment. I went out there and got beat up every day. But eventually I got better than the boxing coach so he stopped coming. Then I got better than the jiu-jitsu guy so he stopped coming. I got a small gathering of students together and basically it was 15 guys would make a circle around me after working out and everybody got to fight me for five minutes. That was what they paid for."

Torres was progressing quickly through the sport and defeating any opponent put in front of him, but sport still hadn't reached a point where it could pay Torres for his trade, especially a fighter of his size.

He found time to pursue his fighting career while still attending Purdue University as a student, never giving up hope that he would still use MMA to become as successful as his father had told him to be.

"I always treated myself as a professional, anything I did was geared towards fighting," Torres said. "Even when it was a fight in a garage with nobody watching, I still was training the way I do now. I always had faith that a division would open for me and I would be known worldwide. It took a long time, I was fighting middleweights and heavyweights, but now it's an emerging class."

Torres has been one of the main reasons the bantamweight class, and the overall popularity of the WEC, has risen in recent years. He holds a 36-1 overall record and is 5-0 in the WEC. He's successfully defended the belt three times with a fourth title defense on the way on Aug. 9 at the Hard Rock Hotel & Casino against undefeated Brian Bowles.

"Miguel Torres has impressed me more than any single other fighter we've had in our organization," said WEC president Reed Harris. "The thing about Miguel is that when a guy challenges him to fight him at his game, Miguel accepts that challenge every time and I haven't seen a lot of fighters do that. He also does a lot for his community, Miguel after graduating from college returned to his area of Chicago and works with those kids."

In August 2007, Torres found himself in a familiar situation, this time in a different role, when he became a parent to his first-born daughter, Yelana.

Yelana's birthdate came at the same moment Torres was training for the first fight of his contract with the WEC. In an effort to be there for his daughter's birth, doctors tried to induce labor two weeks before he had to leave town for Las Vegas.

Attempts were unsuccessful and Torres began preparations to leave for his fight. At the last possible moment however, doctors said the baby was ready to come.

"I remember I went to my house to make sure I had everything I needed, telling my parents to take pictures and videos and thinking I was going to sacrifice seeing the birth of my daughter for my career," Torres said. "But then my girl went into labor it was perfect."

After years of making his father's sacrifices worth it, Torres has received new motivation ever since joining the WEC and the birth of his daughter.

And since he's been pretty much perfect on both accounts, it's impossible to tell which one should scare his opponents more.

"I remember seeing her born and the first thing I thought was, 'I have to do this for her now.' It wasn't just about making my father proud, it was about supporting my daughter."

Brett Okamoto can be reached at 948-7817 or [email protected].

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy