Thursday, April 16, 2009 | 2 a.m.

Call it Andy Stern gone wild.

Sun Archives

- Rival unions' efforts to reconcile will be visible to valley nurses (3-20-2009)

- New coalition, backed by SEIU, leaves Culinary out (3-17-2009)

- Unions clash as card check lies in wait (3-4-2009)

- Nobody wins: Second vote leaves nurses divided, unions' fight unresolved (12-5-2008)

- Board: St. Rose favored rival union (8-12-2008)

Beyond the Sun

The man behind the Service Employees International Union has long been hailed as a visionary within the modern American labor movement, devising strategies that have enabled his union to grow faster than any other in the country. The SEIU has added 800,000 members in the past decade alone.

But some labor experts say Stern’s ambition is reaching new heights, which could ultimately hurt the SEIU and the broader labor movement. His push last month to cut into the membership and turf of Culinary parent Unite Here, the long-standing union of hotel and casino workers, is the latest in a series of controversial moves aimed at increasing membership and consolidating power.

Stern’s efforts to realign labor affiliations — to the benefit of the SEIU — is “a naked power grab,” says John Wilhelm, who once headed the Culinary Union in Las Vegas and now is co-president of Unite Here, whose numbers have been significantly sapped by the SEIU.

Wilhelm accuses Stern and the SEIU of attempting a “hostile takeover of another union’s jurisdiction in a way that is unprecedented in the modern labor movement.”

Nelson Lichtenstein, a labor historian at the University of California, Santa Barbara, characterizes Stern as the modern equivalent of Walter Reuther, the legendary leader of the United Auto Workers, who sought to revitalize the labor movement by leading his union out of the AFL-CIO in 1968 and founding a rival group.

“I think Stern does have a genuine interest in enhancing the movement,” he says. “He feels that this is the moment, so all sorts of things are necessary. Like Reuther, he would say, ‘You can’t make an omelet without breaking a few eggs.’ ”

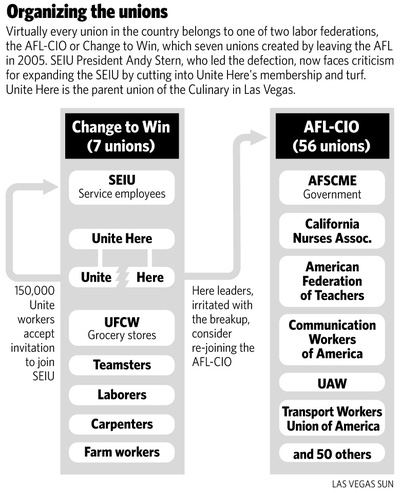

First, some background on the convoluted, recent history of labor affiliations.

In 2004, with complaints mounting that the AFL-CIO was too focused on politics and lobbying and not enough on organizing nonunion workers, Stern issued an ultimatum: “We need to transform the AFL-CIO or build something new.”

The following year, with the AFL not budging, Stern and the SEIU, which mostly represents health care and public sector workers, led six unions in a mass defection, taking a third of the labor federation’s members with them.

To spite the AFL, the rebel unions called their new federation of unions Change to Win — and then denounced union-on-union warfare and championed cooperation.

Another member of Change to Win was a progressive union known as Unite Here, a two-headed organization following the merger the previous year of the Union of Needletrades, Industrial and Textile Employees, known as Unite, and the Hotel Employees and Restaurant Employees International Union, known as Here. Culinary was a member of Here.

But like the marriage of two Type A personalities, leadership of the merged union fought over control of the checkbook.

Over the past six months the leadership struggle has turned nasty between Wilhelm and former Unite leader Bruce Raynor. Raynor calls the merger a failure and encourages former Unite members to break away, while Wilhelm argues that both sides are stronger together as he struggles to keep the merger intact.

Stern, in a kind of passive-aggressive way, promoted the division by inviting either or both sides of Unite Here to simply join the SEIU. Last month at a weekend meeting in Philadelphia, delegates representing 150,000 of Unite Here’s 400,000 members announced they were splitting away and joining the SEIU, swelling Stern’s power base.

Stern had signaled his interest in Unite Here’s gaming turf a week earlier by signing on as a founding member of the Gaming Workers Council, a coalition of unions dedicated to organizing casino workers. Flaring tensions, Unite Here was not invited to the announcement.

Initially, Stern said the SEIU’s goal was twofold: to support the efforts of two other unions — the autoworkers and the transport workers — to win tough contract fights for card dealers, and to organize those workers it has organized elsewhere, such as security guards.

But within a week he raised his sights, welcoming the Unite Here breakaways into the SEIU.

Labor experts say the moves, in some ways, are typical Stern.

“When it comes to organizing, Andy Stern has a sense of impatience,” says Harley Shaiken, a labor expert at the University of California, Berkeley. “He wants to move as rapidly and as effectively as possible.”

Even as he enjoys the spoils of Unite Here’s civil war, Stern says the SEIU is pursuing a “partnership” with the hotel and casino workers, just as his service workers and the rival California Nurses Association are peacefully splitting turf in the health care field: The SEIU will cede nurses to the California union and go after hospital support staff.

“We will organize more workers and change more lives if we work together and collaborate rather than compete,” Stern says. “We can build something bigger together than any individual union can build on its own.”

He says although Unite Here had succeeded in organizing a majority of hospitality workers in Las Vegas and elsewhere, other areas of the country remain virtually nonunion. Other labor leaders agree with Stern that Unite Here’s organizing efforts have come up short.

Experts agree with Stern’s vision, but say the SEIU leader has fumbled the execution, badly.

“It’s almost like you invade another country, occupy parts of it and then extend the olive branch and expect the people you are trying to bring to the negotiating table to be pleased about the circumstances,” says Steve Early, a labor commentator and former union official whose book on the American labor movement, “Embedded With Organized Labor,” is due out next month. “More and more, the ends justify any means in their minds.”

Critics of the SEIU, including Early, suggest that the SEIU’s vaunted growth has come at the expense of worker contracts and strong locals. SEIU’s “growth at any cost” strategy, they say, includes making concessions on benefits and working conditions in exchange for organizing rights.

Those types of arrangements, in addition to the trusteeships of locals, have led to weak union-building, which, in turn, set the stage for local discontent, Early says.

Stern dismisses his critics, saying today’s organizing environment compels such give-and-take, which in time leads to stronger contracts.

Stern says he isn’t letting the labor infighting distract him from the job at hand.

“We are completely focused on working with the Obama administration,” he says. “We always have fights in families. Just because people have fights in their families doesn’t mean people don’t go out and go to work.”

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy