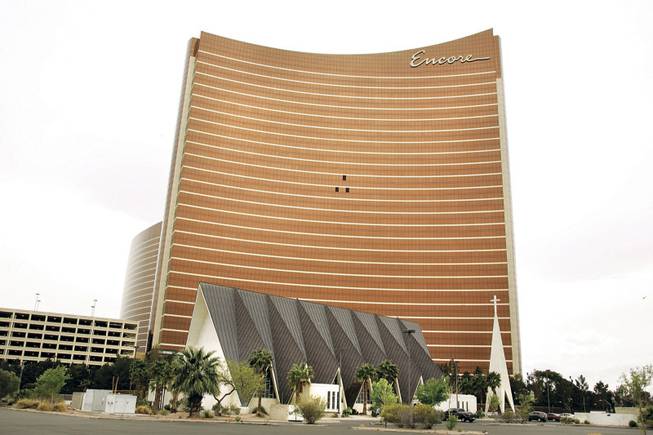

The Guardian Angel Cathedral — seen with its neighbor, the Encore — is a Catholic church on Cathedral Way.

Wednesday, April 15, 2009 | 2 a.m.

Reader poll

Guardian Angel Cathedral

Document

Sun Coverage

Sun Archives

The Guardian Angel Cathedral on the Strip has for decades symbolized Las Vegas’ belief that community institutions can flourish alongside its colossal gaming ambitions.

The Catholic church, at Cathedral Way and Las Vegas Boulevard, in the shadow of Wynn Resorts’ Encore, now stands in the way of Steve Wynn’s long-term plans to build a casino on the company’s 140-acre golf course next to Wynn Las Vegas.

It’s an unanticipated consequence of a 1997 law that established an unrestricted gaming corridor along Las Vegas Boulevard, while adopting tougher restrictions on casino construction beyond the Strip — among them a requirement that casinos be at least 1,500 feet from churches and schools and 500 feet from homes. The law is also preventing Marriott International and Golden Nugget from moving forward with plans for casinos on land they own near churches.

The companies’ proposed solution is Assembly Bill 476, which would expand the Las Vegas Gaming Corridor to include the land the companies intend to develop.

The corridor, where developers may build as many casinos as the city or county will allow, extends 1,500 feet on either side of Las Vegas Boulevard, from the Stratosphere on the north to St. Rose Parkway on the south. The bill would expand it to include downtown land bounded by U.S. 95, Las Vegas Boulevard, Bridger Avenue and the Union Pacific rail line. The proposed expansion would also include land east of the Strip, bounded by Paradise Road to the east and Sands Avenue to the south.

Portions of Wynn’s 18-hole golf course closest to the Guardian Angel Cathedral run afoul of the distance requirement spelled out in the law. Left unchanged, the law would require Wynn to build his casino on the golf course land farthest from the Strip and the church.

A portion of Marriott International’s property, on the west side of Paradise Road, bounded by Convention Center Drive to the north and Desert Inn Road to the south, is also too close to the Guardian Angel Cathedral to allow a casino.

Golden Nugget stands to benefit from the bill because it recently purchased land for expansion near the casino, at the southwest corner of Fremont Street and Casino Center Boulevard. St. Joan of Arc Catholic Church is a couple of blocks south on Casino Center.

Attorney Mark Fiorentino, who represents the three companies, said there is little opposition to the bill because the proposed casinos are in urban areas close to gaming. Surrounded by gaming, the churches in question aren’t opposed to additional casinos in the neighborhood, he added.

“No one would say with a straight face that these ... aren’t urban areas,” Fiorentino said.

But the plan, which received unanimous approval from the Assembly Judiciary Committee on Friday, isn’t without critics. The bill will next be voted on by the Assembly.

MGM Mirage and the Culinary Union oppose expansion of the gaming corridor, saying it violates the principle behind the 1997 law. Developers shouldn’t be able to avoid long-established rules for casino expansion by getting a pass from the Legislature, MGM Mirage spokesman Alan Feldman said.

The 1997 law virtually stamped out the prospect of new casinos in established neighborhoods while benefiting established operators that had bought land for casinos beforehand. The limitations, however, didn’t hamper the construction of many casinos just outside the Strip corridor in recent years because these casinos, including the Palms, Rio and Hard Rock, were planned before the law took effect. These casinos are located in Gaming Enterprise Districts, which, like the Las Vegas Gaming Corridor, are self-contained zones permitting casino construction without distance limitations.

MGM Mirage and the Culinary Union’s opposition to the bill led to a redrawn proposed gaming corridor bounded by Sands Avenue to the south and Paradise Road to the east. It still includes the Wynn Las Vegas golf course and Marriott-owned land. The original expansion would have extended the gaming corridor as far west as the corner of Tropicana Avenue and Paradise Road and a wide swath of downtown Las Vegas from the Stratosphere to U.S. 95.

Culinary Union Political Director Pilar Weiss testified against the bill in its original form, but didn’t testify in opposition to the revised plan. Other trade unions involved in construction, including the Building Trades Association, have supported the bill.

City and county officials said they are neutral on the bill, while other casino giants — which either support the bill or are reserving comment — have not publicly opposed it.

Representatives of Wynn Resorts, the Golden Nugget and Marriott International could not be reached for comment.

Assemblyman Richard “Tick” Segerblom, who represents downtown Las Vegas and is vice chairman of the Assembly Judiciary Committee, opposed the initial plan because it would have allowed developers to build casinos next to homes in long-established neighborhoods.

“Gaming belongs south of the Sahara, not in historic neighborhoods” such as Beverly Green and Southridge, where additional casinos could depress home values and hurt efforts to encourage people to live closer to downtown, said Jack LeVine, a real estate agent specializing in vintage homes who initiated an e-mail campaign against the original bill.

Fueled by local opposition in his district, Segerblom succeeded in redrawing the city boundaries of the gaming corridor expansion to exclude residential neighborhoods. The compromise includes land the Golden Nugget bought recently for expansion.

Segerblom voted for the compromise but isn’t happy with the bill, calling it developer-sponsored planning that should be the purview of government.

It expands gaming when it isn’t needed in this economy, he said, especially with Strip gaming giants on the verge of seeking bankruptcy protection and Boyd Gaming mothballing its unfinished Echelon resort development on the Strip.

“This adds competition at a time when existing casinos are having a hard time,” Segerblom said.

Big casinos should be concentrated on the Strip, where planners can address traffic patterns and other concerns, he added. “We’d like to see the Strip built out before we start building (additional casinos) on Paradise.”

Developers are proposing the bill now so they can begin planning resorts to be built years from now, once the economy rebounds, Fiorentino said. Marriott, for example, bought nearly 14 acres near Convention Center Drive and Paradise Road for $220.5 million in 2006 and 2007, county records show.

Because the bill enables competition near the Strip, it may not be welcomed by established companies there but will benefit Las Vegas in the long term, according to UNLV economics professor Bill Robinson.

Having two companies, MGM Mirage and Harrah’s Entertainment, owning the majority of Strip casinos is bad for tourism, he said.

“What we have now is an oligopoly ... which lowers innovation and creates copycats instead of innovators. You have to have strong competition in your industry and the possibility of new people coming in and new ways of doing things.”

Encore is nearly a mirror image of the Wynn Las Vegas, from the brown glass exterior to the style and placement of the logo — and it's just as luxurious as the original. Some call Encore the younger, hipper sister of Wynn.

Located steps from Wynn Las Vegas, yet under the same roof, Encore's fanciful and intimate atmosphere is unlike anything anywhere, with an environment that is uniquely Wynn and distinctly Encore.

Steve Wynn spared no detail in his newest property when designing Encore. The casino floor is decorated in rich reds, browns and purples with mosaic butterflies embedded into the marble floors and fresh flowers greeting guests in the casino atrium.

Luxury doesn't end of the casino floor. Encore boasts 2,034 impeccable guest rooms and suites. The standard suites resort accommodations are 700 square feet with the larger suites measuring in at 5,800 square feet. Standard suites guest rooms feature plasma screen TVs, high-end bath products, spectacular views of the Strip, and also plush linens and mattresses, which can be purchased in the Encore store, in case you can't get enough.

Dining options include Chef Theo Schoenegger's fine Italian cuisine at Chef Theo Schoenegger's, Sinatra's and the pan-Asian café creations of Chef Jet Tila at Wazuzu.

Guests can also dine on steaks and chops at star Botero Steak. At Switch, Encore's French restaurant, the walls come to life mid-meal and your surroundings appear to change before your eyes. For decadent, hip Asian dining before or after a night at one of resort’s ultra-chic nightclubs, visit Andrea’s, the newest dining experience at Encore.

XS headlines Encore's nightlife and pool party scene while Danny Gans takes care of humor and entertainment. Encore also features two of the most celebrated nightlife experiences in Vegas, XS Nightclub and Surrender. Both feature main room dance floors that flow outside to pools, patio spaces and gaming areas.

When the temperature rises, don’t miss Encore Beach Club, the premier daylife destination that features three tiered pools and luxurious cabanas and bungalows with private infinity pools.

Encore Esplanade features 11 high-end retail stores, with brands like Hermes, Chanel, Loro Piana and Rock, and Republic Piaget luxury watches. The resort also has a Forbes Five-Star spa, a salon and an 18-hole, on-site golf course, which is adjacent to the Wynn.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy