Sunday, Sept. 14, 2008 | 2 a.m.

Beyond the Sun

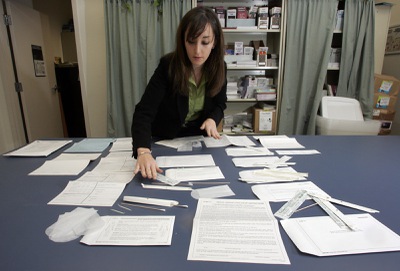

If you can bring yourself to call the police, or drive to the hospital, this is where you will end up: In the emergency room, tucked into a private examination area, half-naked, answering questions, posing for photographs and waiting for the pelvic exam to end.

Almost every sexual assault victim in Southern Nevada, almost every rape victim in the lower half of the state, lands under the white lights of this examination room at University Medical Center. It’s the single facility where they can have forensic evidence scraped and siphoned from their bodies — provided, of course, they report the attack.

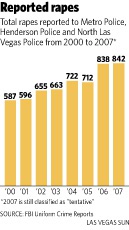

Fewer than half will, according to the conservative estimates. Next year, however, all this could change.

Of the numerous reasons rape victims resist reporting the crime — shame, self-blame, shock — fear may loom largest. Filing a police report and risking retaliation is a ghastly prospect when the person who assaulted you is an acquaintance, and the majority are; boyfriends, husbands, exes, co-workers, friends.

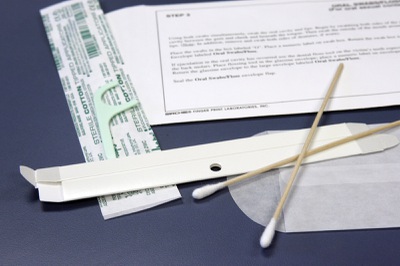

And in Clark County, if the victim does not want to press charges, a forensic sexual assault exam isn’t always conducted. This means that in some cases, no evidence is gathered, no photographs are taken, and no police report is written up. It stings worse a few weeks later, when the victim realizes she really does want to press charges. Too late.

For rape victims, the body is the crime scene, and the evidence lasts only as long as the bluest bruise.

This is why, starting Jan. 5, Nevada will be federally mandated to give victims who don’t want to cooperate with police the option to have a forensic sexual assault exam. Nurses currently decide whether to give the exam in these circumstances; next year every victim will be offered the test and protected from having to name names.

The state will also be required to store any evidence collected during these exams, even though the files may sit unused on a shelf in some eternal evidence locker. The new laws are a product of the Violence Against Women and Department of Justice Reauthorization Act of 2005, and the logic behind them is simple: Give victims time to decide whether they want to pursue their cases. Don’t force a decision in the immediate aftermath of a traumatic event.

If Nevada isn’t in compliance with the new regulations by Jan. 5, the state will be barred from $1.2 million in federal grant money issued annually to assist female victims of violent crime. Funding that, if taken away, could cripple the efforts of victim advocates, police and prosecutors in the state.

So now stakeholders from every facet of the criminal justice system — police, prosecutors, social workers, hospital officials, nurses, nonprofit victim’s advocates and representatives from the attorney general’s office — have to figure out how to pull it off. In Southern Nevada, they’ll be getting together Wednesday to discuss this very matter. Until then, however, nobody is sure how we’ll embrace a totally different system in the space of four months. And quietly, some are questioning whether certain elements of the new procedure will hinder police investigations instead of help.

At its core, the federal act speaks to a subtle but significant shift in the way we approach sexual assault. Instead of pressuring a hesitant victim to tell her story immediately so detectives can chase down leads, the victim can keep quiet until she’s comfortable. The primary concern is not the investigation of a crime, in other words, but the well-being of the victim. This may reflect an increased sensitivity to the psychology of sexual assault. Or perhaps it’s a function of our growing appetite for forensic crime solving. We are comfortable letting a victim remain quiet now because we know we have the DNA, the saliva, the fingernail scrapings.

Even if she’s quiet, the science will talk.

Early media accounts of the 2005 Violence Against Women Act, called VAWA, incorrectly reported that states would be required to offer anonymous “Jane Doe rape kits” — forensic tests cataloged according to private PIN numbers, not names. Although states don’t have to offer the Jane Doe tests, they can individually decide to do so. This is happening in some parts of the country, though not everyone in Nevada is certain it’s the greatest idea.

It might be difficult for a traumatized person to memorize a number, or save a scrap of paper that holds the key to her case, said Andrea Sundburg, executive director of the Nevada Coalition Against Sexual Assault. If victims don’t have to give information about their attackers, they could reasonably provide their names to police, who would keep them in confidence. If a DNA sample linked one assault to a series, cops could call protected victims and tell them their testimony might help take down a serial rapist, Sundburg said.

And although VAWA mandates the storage of evidence from victims who aren’t pressing charges, it stops short of saying just how long each state should hold that evidence. This will be determined by Nevada’s stakeholders after that Wednesday meeting. Sundburg says she could live with just 90 days of storage, even though Nevada law gives victims four years to file a written report to keep their case alive. Ninety days is not ideal, she said, but acceptable. Louise Torres, executive director of Las Vegas’ Rape Crisis Center, would like to see the evidence held for years, if not forever.

It’s easy to dream when you’re not storing the stuff. Though Metro Police aren’t willing to comment on the changing law just yet (they want to wait until after the Sept. 17 meeting) it’s easy to infer that storage is a concern. Currently, Metro holds forensic evidence from rape victims who are pressing charges indefinitely. Adding evidence from victims who may never press charges presents a space issue, not to mention questions of time and money.

It’s hard to know whether storing a bunch of anonymous DNA will be worth it in the end. Surveys of crime victims who have called help hotlines indicate many would seek medical assistance and testing if they didn’t have to tell police, but this research is small in scope and doesn’t directly speak to the issue at hand: Will victims want to work with police months after the fact?

If the law works the way it’s intended, more victims will feel comfortable seeking out forensic tests. Even if they never decide to press charges, the state will start to build a database of DNA, and, in time, police may be able to see patterns in crimes or repeat offenders. And who knows what the promise of future forensic science might hold.

“The ultimate dream,” Sundburg said, “is that all these kits are processed.”

Of course, more forensic tests means more work. Clark County has three certified “sexual assault nurse examiners,” specialists trained to conduct forensic rape examinations. Last year, those three nurses typically handled 70 to 80 cases a month — that’s 840 to 960 cases annually — already an incredibly high workload, according to Carey Goryl, executive director of the International Association of Forensic Nurses. Last month, the nurses saw 90 victims.

Each exam costs about $750, and the county picks up the tab, as required by law. UMC still loses money on the tests, which the hospital’s emergency medicine chairman, Dale, says he doesn’t mind. Still, the increased costs could add up. This may be why, though people have been advocating victim-first sexual assault investigations for years, not much movement has happened until now.

People don’t like to talk about things that cost money, Torres said. Moreover, they don’t like to talk about rape and sexual assault.

The 2005 VAWA act — which many say owes its existence to Democratic vice-presidential candidate Joe Biden, who lobbied for the act’s initial passage in 1994 and saw it reauthorized three years ago to include these new regulations — may be a sign the times are slowly changing. The New Republic called it “Biden’s signature accomplishment in domestic policy.”

But will it work? Privately, police are nervous. They fear that if victims are not required to name their attacker at the outset, then law enforcement is robbed of an opportunity for critical evidence gathering, going to the place the crime happened and finding witnesses or suspects.

Prosecutors will have their work cut out for them as well. James Sweetin, Clark County’s chief deputy district attorney in charge of the special victims unit, said charging someone with rape three months — or even three years — after the attack, isn’t impossible, just much harder.

But easing victims’ trauma now trumps the importance of putting someone in handcuffs. In time, we’ll see whether victims who know they don’t have to talk to police will be more likely to seek help, whether giving a victim time to make the decision will encourage more arrests in the long run, and whether arrests are really the most important thing to come out of that emergency examination room anyway.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy