With some of the technology of his research work around him, Biswajit Das, director of the Nevada Nanotechnology Center at UNLV, discusses his four patent applications.

Sunday, Sept. 7, 2008 | 2 a.m.

Detecting pollution, mold

Patented innovations developed from UNLV research include:

• A method of detecting pollution in water using ultrasonic energy. “Sonication” breaks down compounds in the water, and comparing before and after tests of the water will reveal whether pollutants are present at industrial sites or sites potentially contaminated with hazardous waste. The method is relatively inexpensive, quick and simple, and tests can be performed on-site. The patent was issued in May 1996.

• A faster way to identify a potentially dangerous type of mold in buildings, cutting the time it takes to get results from days to hours. The mold this method detects has been linked to respiratory illnesses, central nervous system disorders and immune system dysfunction. The technique detects specific microorganisms by amplifying their unique DNA sequences. The mold is typically hard to identify. The patent was issued in May 2004.

Beyond the Sun

Biswajit “BJ” Das is a scientist with big ideas about small things — things so tiny they are measured by the nanometer, a unit of length about one-one hundred thousandth the width of a human hair.

For instance, Das’ lab at UNLV has filed an application to patent a device that stores digital data on silicon nanocrystals, which could give rise to computers that are lighter and more compact.

Nano-things will change the world in giant ways, Das thinks. Inventions arising from research at UNLV also could help transform the character and economy of Southern Nevada.

Das and other business-minded professors want to turn their innovations into marketable goods, spurring fledgling industries, creating jobs and encouraging still more research at the university.

In past years, however, researchers at UNLV made discoveries, published papers on them, accepted plaudits from colleagues and moved on to new projects. Few bothered to work with local companies to commercialize their ideas.

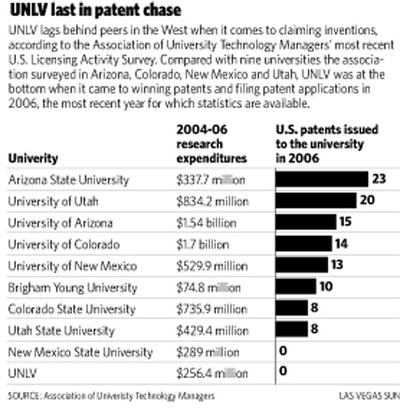

As a result, the university lags behind its peers in the West when it comes to claiming inventions. With a key hire seven months ago, UNLV is trying to change that.

After completing projects, faculty members can send their universities “disclosures,” forms outlining discoveries that could be patented. Academic institutions typically own the rights to any inventions their researchers create.

From 2004 to 2006, UNLV registered one disclosure for every $14.2 million it invested in research, according to the Association of University Technology Managers’ most recent U.S. Licensing Activity Survey. Of nine universities the association surveyed in Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico and Utah, all booked at least one disclosure for every $5.4 million they spent on research.

Compared with those nine schools, UNLV was also at the bottom when it came to filing patent applications, submitting 10 in 2006, a fifth as many as Arizona State University and Brigham Young University. UNLV has won just four patents, issued 1996 to 2007.

Local economic driver

Institutions that obtain a lot of patents can help shape regional economies, spawning spinoff companies dedicated to marketing inventions.

“This is important for Las Vegas because this is a particular kind of economic development that could complement your ability to generate large numbers of jobs,” said Mark Muro, policy director at the Brookings Institution’s Metropolitan Policy Program.

At Colorado State University, one professor’s idea for manufacturing low-cost solar panels led to the creation of a local start-up devoted to producing them. The business’s payroll has grown from four employees a year ago to about 80 today. A manufacturing plant scheduled to open next year will create hundreds more jobs.

Often, existing private companies pay schools a fee and a cut of future profit for the right to use researchers’ innovations to develop products.

“Economies can grow just by getting bigger and having more people working at lower- or middle-wage jobs, but to really prosper, you really have to have those higher-value-added innovation-based jobs,” said Rob Atkinson, president of the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation.

For years, the Las Vegas Valley has hitched its fortunes to the hospitality and entertainment industries. But for the region to establish itself as a powerhouse in fields such as alternative energy and biotechnology that generate higher-paying jobs, UNLV might have to raise its invention quotient.

Though the university still devotes less money to research than many of its peers, its spending in that area has surged over the past decade. In the 2006-07 fiscal year, UNLV secured nearly $75 million in research funding from outside agencies, more than seven times the amount it brought in 10 years earlier.

The next step is to figure out how to put that research to use.

In Arizona ...

Recognizing the role that higher education institutions can play in strengthening local industry, other states have begun making big investments in research at state universities.

Arizonans voted in 2000 to raise the state sales tax by 0.6 percent to fund education, with a slice of the proceeds going to universities to pursue technology and research initiatives.

Jane Dee Hull, the state’s Republican governor at the time, supported the tax hike, saying, according to a University of Arizona news release, “Arizona has a choice. We can become the Silicon Desert, with high-tech companies and high-paying jobs coming here, or we can become a minimum-wage wasteland.”

The cash infusion, more than $50 million over the past two years for the University of Arizona, funds research programs there that explore topics ranging from water use to optical sciences and ways to diagnose, treat and prevent diseases such as diabetes and cancer. The school has used the money in hiring new professors, applying for patents and developing businesses related to researchers’ inventions.

In Nevada, where the governor believes the state has a spending problem, the story is different.

“None of us expect the state to chip in, so we’re looking at private money, foundation money, federal support. That’s our responsibility,” said Robert Sweitzer, director of technology transfer at UNLV. His division specializes in turning research into products or services that sell.

To be fair, Nevada’s expenditures on higher education have grown rapidly over the past decade as inflation and a ballooning population have increased colleges’ expenses. This fiscal year, UNLV received about $200 million from the state general fund for day-to-day operations, up from less than $150 million five years ago. The Legislature invested millions of dollars in a science and engineering building scheduled to open at UNLV in late fall.

But as Sweitzer pointed out, when the new space comes online, the university plans to shut down several older chemistry and biology labs because it can’t afford to staff them.

And that’s just one problem. Pay for graduate researchers is dismal compared with that at other institutions. Budget cuts have forced the university to increase class sizes and faculty teaching loads, leaving professors with less time for research that could yield inventions and patents.

Sweitzer came to UNLV in February. He previously worked for a New Mexico company that specializes in commercializing new technologies.

He now has a Detroit company interested in CardSleuth, a technology Hal Berghel at UNLV co-invented that allows people using a hand-held scanner to detect everything from counterfeit driver’s licenses to hotel keys bearing stolen credit card information on their magnetic stripes.

Berghel, founding director of UNLV’s School of Informatics, had finished his work on CardSleuth and moved on to other projects when Sweitzer approached him with information about the Michigan company that might be interested in marketing the invention. Now, UNLV and the company are drafting a contract to allow the business to sell CardSleuth to law enforcement agencies, private security businesses and other clients.

UNLV gives researchers 60 percent of the net proceeds it earns from commercializing their inventions, so Berghel will get royalties if CardSleuth is a success.

Sweitzer thinks many UNLV professors, like Berghel, have made potentially lucrative discoveries but have not sought to patent or market their work.

“They’re not exactly trained to be able to approach a corporation or be able to know what to say to them and get them interested. They’re scientists,” Sweitzer said.

That’s where he comes in.

His job “is to say, ‘OK, what can we do as an encore to this research breakthrough to see to what degree this would impact people’s lives?’ ”

UNLV has 21 applications pending with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, 14 of those filed after he arrived. Besides CardSleuth, the university is looking to protect discoveries such as a method of reprocessing spent uranium fuel so it can be reused in a nuclear power plant, and a method of controlling the diameter of carbon nanotubes made in a lab — one of four patents Das is seeking.

Sweitzer’s office, created in 2005, was vacant for about half a year before he arrived. His predecessor, who was suffering health problems, had left UNLV to move closer to family.

Ron Smith, vice president of research and dean of the graduate college, said he wouldn’t describe the former technology director as ineffective. Nevertheless, when Smith took his current position about two years ago, faculty members told him UNLV “had not been responsive to taking their research products into the marketplace.”

UNLV’s white knight

To help fix the problem, the university hired a patent lawyer in July 2007. It conducted two searches before landing Sweitzer, who seems intent on transforming the institution’s culture when it comes to technology transfer.

In the 2007-08 fiscal year, UNLV made $25,000 from allowing corporations or other entities to use its intellectual property. Sweitzer wants to raise that figure by $100,000 by next fall.

Various deals are in the works. A New Jersey biotech company, for example, is negotiating for the rights to develop a commercial product from a new drug developed from UNLV research. The patent was issued in September 2002. The drug determines whether typical cancer treatments — such as chemotherapy medicines — are actually doing their job of killing cancer cells. It’s difficult to tell whether cancer cells are actually dead or whether they’re injured and could recover. The new drug is more effective in determining the health of those cancer cells and shortens the time it takes to get lab work done.

Sweitzer also is working with entrepreneurs to launch start-ups that sell products based on UNLV inventions, and hopes to announce new companies this year. Working with local businesses and entrepreneurs to create products is a priority, Sweitzer said.

The UNLV Research Foundation is looking to partner with private developers to build a 115-acre research and technology park with laboratories and offices at Durango Drive and Sunset Road that would foster collaboration between UNLV researchers and private businesses.

To gain professors’ trust, Sweitzer said, he needs to show them results.

Das, for one, is pleased that Sweitzer has been so active.

And with Sweitzer’s help, the tiny things Das creates could soon be making UNLV money as they find their way from his high-tech workroom into your iPod, your digital camcorder, your office, your home.

Sun reporters Phoebe Sweet, J. Patrick Coolican and Joe Schoenmann contributed to this story.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy