Sunday, Oct. 19, 2008 | 2 a.m.

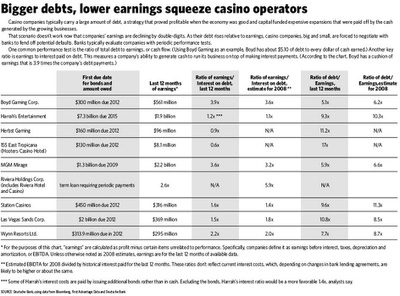

Casino companies’ earnings are plummeting by double digits. Debt costs are rising for many companies. And their customers are spending less.

In the financial world, in this economy, those are the trend lines of doom.

Indeed, a few smaller operators are already close to bankruptcy. But could giants like MGM Mirage and Harrah’s Entertainment be next?

The breathtaking series of Wall Street failures and Washington bailouts of recent months suggests anything is possible — even spectacular failures in Las Vegas.

For now, bankruptcy protection remains a remote, if grim, possibility for all but the most damaged companies. Experts say that banks will negotiate with the big casino operators rather than force them into bankruptcy.

“These companies are still generating a huge amount of cash. The banks are going to work with operators that are willing to cut back on capital expenditures,” said one banker, who requested anonymity.

Yet financial experts say for the casino giants to survive in this economy, they must continue to make smart, sometimes painful moves. They also need a little of that luck so many people come here to find.

Casino executives and analysts interviewed by the Las Vegas Sun last week were entirely aware of the industry’s plight as they explained the steps needed to shore up these companies.

The chief concern among casino operators remains how long the economic downturn will continue. The deeper and more prolonged the downturn, the more likely that companies will be forced into bankruptcy.

In the meantime, casino operators are pursuing options to cut costs and hold creditors at bay.

Harrah’s recently completed an inter-company loan of $200 million to trim the company’s debt. It’s now paying a portion of its interest by issuing additional bonds, saving the company millions of dollars in cash.

Station Casinos will seek some reprieve from its banks, though the company’s debt costs will likely go up, analysts say.

Both companies have relatively little cash left after interest payments to pay for upgrades to their properties.

Casino operators are also cutting costs where they can, including payroll, their single largest operating expense. At many companies, this has meant laying off managers and rank-and-file workers in recent months.

As of August, the state reported that the gaming industry employed roughly 600 fewer people than a year ago. Although more workers have lost their jobs in that time, these figures reflect that many people who lost jobs have since found work, especially at new casinos that are hiring or have opened.

Some companies have halted construction projects, and analysts expect more plans to be put on hold in the coming months. (The exceptions are big projects too far along to mothball, such as MGM Mirage’s CityCenter and the Octavius hotel tower at Harrah’s-owned Caesars Palace.)

Some executives are putting more cash, or equity, into their companies. Las Vegas Sands Chief Executive Sheldon Adelson, the company’s largest shareholder, recently lent the company $475 million of his own money to pay down debt.

Companies with wealthy shareholders could do the same, analysts say.

Still, some companies may not be able to wait out the economic downturn. Herbst Gaming and the owners of the Hooters hotel, for example, are not generating enough cash to cover debt payments.

A rebound by 2010 would be soon enough for companies to get a reprieve from lenders and weather the downturn, experts say.

Yet with gaming stocks and bonds trading at less than 50 percent of their value of a year ago, most investors aren’t hopeful for a quick turnaround.

Some experts believe there might be a cultural shift at play with longer-term implications for businesses, especially the Las Vegas resort industry, which encourages escapist, spendthrift behavior.

“Post the era of using homes as ‘piggy banks’ and overspending as a nation at every level, we believe a new era of national thrift is before us,” Andrew Zarnett, a bond analyst with Deutsche Bank, said in a research report last week. “We believe last week’s activities in the stock market have caused too much psychological damage and the general public has been traumatized by these events ... We believe Americans will be forced, if not at their own volition, to reduce household debt.”

The result, Zarnett says, will be reduced consumer spending and an unprecedented gaming industry recession.

For several casino companies, the economy began its slump soon after they took on massive debts. At the tail end of the credit boom, Station Casinos and Harrah’s went private with the help of private equity firms that borrowed extensively to make the deals happen.

Ideally, leveraged buyouts rely on cheap loans that are paid down by growing earnings over a longer term than is acceptable to Wall Street. The companies can then be sold back into the public market for more money.

It’s hard to blame these companies for taking on debt when they did because few business models would have assumed a decline this deep, according to one Las Vegas casino executive, who requested anonymity.

“Nobody considered a situation where your cash flow goes down by 25 percent because that would have been a ridiculous assumption to make a year ago,” the executive said. “You would have been laughed out of the room.”

Before the economic decline, major casino companies used cheap capital to build expensive properties and acquire others. Lenders gave them money at attractive interest rates on the assumption they would generate enough cash to pay off their ballooning debts, or at least refinance them at lower rates.

The credit crisis, by itself, wouldn’t have been too dire for casino companies. As long as casinos generate huge amounts of cash that grow over time, as well-run casinos have throughout history, even monster debts can be managed.

Operators have seen boom-and-bust cycles before, and the Strip has historically functioned with some independence from the broader U.S. economy.

Yet in this downturn consumers of all income levels are spending less, contributing to double-digit earnings declines at some casino companies. Those factors have shifted the industry’s economic outlook.

“If you thought this kind of thing would happen, you wouldn’t do any deals, ever,” the casino executive said.

Michael Paladino, senior director of gaming, lodging and leisure companies for bond rating agency Fitch Ratings, calls this an “unprecedented consumer downturn, relative to the size of the industry today.”

Companies that didn’t borrow billions of dollars to go private have their own set of concerns: All casino companies have terms, or covenants, with their banks.

MGM Mirage, whose bank lenders for the company are some of the same entities that are lending money to the company’s CityCenter joint venture, recently negotiated some relief. The banks are allowing the company to increase its ratio of debt to earnings in exchange for a higher interest rate.

Although many companies don’t have any bonds coming due until at least 2010 or thereafter, MGM Mirage has a pair of bonds worth about $1.3 billion that mature next year. The company will likely take on additional bank debt or refinance the bonds at higher rates, analysts said.

Las Vegas Sands expects to open a casino resort in Bethlehem, Pa., next year and condos at its Palazzo resort in 2010, but those projects alone might not generate enough additional cash to satisfy the company’s banks, especially if earnings are depressed, analysts said. Meanwhile, the company is sinking billions of dollars into a stretch of resorts in Macau that may not boost profits for years.

Wynn Resorts has more of a cash cushion than many of its competitors. As a preemptive strike, Wynn negotiated more leeway on the company’s debt without having to pay higher interest rates for it. And yet, Wynn is also facing an earnings decline that, should it continue, could put the company’s banks in the position of calling the shots, analysts said.

These problems could be solved in an instant — by earnings growth.

In the meantime, companies will further tighten their belts. This may mean further staff cuts or delays of periodic upgrades to, say, hotel room furniture or restaurant interiors — an unappealing prospect in a business where customers expect to be coddled and entertained, even dazzled.

In a worst-case scenario, companies could sell property or land. The credit markets would have to improve first because few companies would have the ability to finance a purchase otherwise, Paladino said.

However prolonged the downturn, Paladino said the industry will eventually look different, perhaps with less reliance on debt to fuel growth.

“Nobody’s saying that banks aren’t going to lend again,” he said. “But the longer it takes, the worse things are going to be for this industry.”

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy