BLOOMBERG NEWS FILE

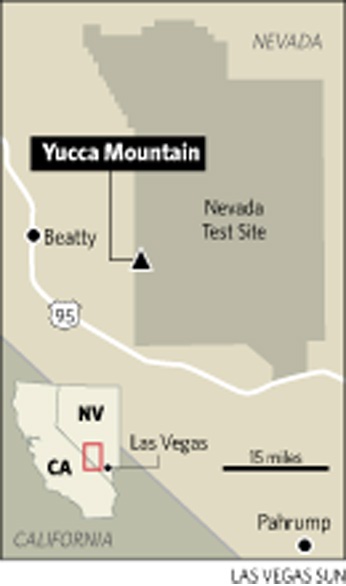

The U.S. Energy Department plans to store spent nuclear fuel at Yucca Mountain, an extinct volcano about 90 miles northwest of Las Vegas.

Sunday, Oct. 12, 2008 | 2 a.m.

Sun Topics

The sound bites are simple:

John McCain supports plans to store high-level nuclear waste 90 miles from Las Vegas at Yucca Mountain.

Barack Obama does not.

The question being asked by Nevadans who oppose the repository — and by those who support it, too — is whether that matters. What could each candidate actually do about it as president?

The short answer is that the next president may be the only thing standing between train loads of radioactive waste and a hole in the Nevada desert.

First, though, a more nuanced view of where they actually stand:

• McCain “supports Yucca as long as it meets environmental and safety concerns,” according to his Nevada spokesman, Rick Gorka.

McCain’s position harks back to Bush’s vow to let “sound science” dictate whether Yucca was the best site for a deep geologic repository for nuclear waste. Bush has been an advocate of the project.

“Sound science has become, in the nuanced language of nuclear politics, a wink and a nod to say, ‘I’m all for it,’ ” said Democrat Richard Bryan, a former Nevada governor who represented the state in the U.S. Senate for more than a decade. “Sound science is a euphemism.”

McCain wants 45 new nuclear power plants by 2030, a goal that would be much harder to reach without a plan for long-term disposal of the dangerous waste. And he supports waste reprocessing, which is common in Europe but outlawed in the United States over fears it would lead to nuclear weapons proliferation.

• Obama, too, supports nuclear energy as “part of the mix,” although he doesn’t plan to support new plants with federal dollars, at least until safety and security problems are addressed. The industry has said more plants are unlikely without hefty federal support.

Unlike McCain, Obama has said he does not support a plan to store waste at Yucca. He said he thinks the mountain is unsafe as a geological repository. He does, however, say that another long-term storage option will be necessary.

Obama has pledged to lead a search for the safest way to store nuclear waste, said his Nevada spokeswoman Kirsten Searer. In the short term, storing waste at power plant sites across the country is the best option, she said, although it might not be the best long-term idea.

During the 1950s, Congress enticed private utilities to build nuclear reactors in part by agreeing to take on the liability for large accidents at power plant sites, a guarantee no private insurance company would provide.

The federal government also signed agreements with utilities to store their radioactive waste permanently, in part because of concerns it would fall into the wrong hands and be used to make nuclear weapons. The Energy Department was to take possession of the waste by 1998.

The nuclear power industry took off in the 1960s and 1970s. New power plants across the country churned out waste that they stored on site, waiting for the government to take possession.

Toward that end, Congress approved The Nuclear Waste Policy Act of 1982, ordering the Energy Department to select at least five storage sites for analysis.

By 1983, the department had nine sites in six states on its short list.

Then the landscape changed. By 1987, the department was considering just three sites, one in Texas, another in Washington, the third at Yucca Mountain.

During hearings in 1986 and 1987, it became clear that a repository would be controversial. When the Washington delegation asked the Energy Department for the data to back up conclusions that a repository in Hanford on the Columbia River was feasible, the department admitted it had lost much of the data, said Bob Loux, former executive director of a Nevada state office that exists solely to fight the project.

It was the first major blow to the Energy Department’s credibility, he said, and one that opponents would refer to when shoddy data gathering procedures were revealed almost two decades later.

As controversy grew, legislation was proposed in Congress in 1987 to scrap the selection process and start a new method of finding a site. But the bill failed.

Instead, Congress went the opposite way. It passed the Nuclear Waste Policy Amendments Act of 1987 directing the department to study just one site: Yucca Mountain.

Opponents of Yucca pointed to the legislation, which they dubbed the “Screw Nevada Bill,” as proof that the site selection process had become political rather than scientific. Nevada in those days was a political lightweight compared with Texas and Washington.

The bill further galvanized Nevada against the project.

The state’s federal lawmakers arose in unanimous opposition and have not wavered.

The state had created the office dedicated to fighting Yucca in 1985. Now, led by Loux, the Nevada Nuclear Projects Agency assembled armies of scientists and lawyers to fight the project at every turn, challenging the science and the legislation, and aggressively courting public opinion.

Over the years since, the issue has proceeded on many fronts. The highlights:

Temporary storage

In the 1980s, the Energy Department, wary of the approaching 1998 deadline on waste, looked for states or Indian tribes willing to store the waste temporarily while a permanent site was developed.

The only proposal was for a Goshute Indian reservation in Western Utah. The Nuclear Regulatory Commission approved an interim storage facility on the reservation in the ’90s.

But after much controversy, the Bureau of Land Management denied an application to transport waste to the site, thwarting the consortium of private nuclear utilities proposing the facility.

A law blocks temporary storage of the waste in Nevada.

When the 1998 deadline for the feds to take responsibility for nuclear waste nationwide passed, utilities began to try to force the issue by filing lawsuits against the government.

Radiation exposure

The single greatest issue with Yucca Mountain is whether the storage would be dangerous to people living nearby, or who live along highways and rail lines over which the waste would be shipped.

In 1992, Congress passed the Energy Policy Act, which directed the National Academy of Sciences to study what kind of radiation standard the Environmental Protection Agency should enact to best protect people living near the site.

The academy issued a report that said a standard should last as long as radiation from the mountain posed a risk to the public.

In 2001, the EPA finally released its standard. The agency set a conservative exposure limit for the first 10,000 years, but provided no standard for the years that followed.

Nevada sued, arguing that 10,000 years was not long enough. The peak exposure would occur sometime after that, the state said.

In 2004, a court ruled that the EPA must revise its standard. It did so last month, setting radiation limits for 1 million years.

Structural flaws

In the ’90s, flaws emerged in the Energy Department’s assumptions about how water moved through the mountain, according to the Nuclear Projects Agency. The department had thought water moved in what it called a matrix — meaning one rock must be saturated before the next would begin to absorb water. That would mean it would take many thousands of years for water to reach through a thousand feet of rock to where highly radioactive waste was being stored.

At the time, Energy Department and Nuclear Regulatory Commission rules said that if water moved from the site into an environment accessible to humans in less than 1,000 years, the site would be unsuitable, the agency says.

But because the mountain is made up of highly fractured rock, scientists found that water actually moved through the site much faster than expected.

Opponents seized on the finding to argue that radioactive water from the mountain would find its way along a natural course that would take it to nearby Death Valley National Park.

Rather than disqualifying the site, the Energy Department changed the rules, Loux said. Instead the Energy Department must demonstrate that it would meet the EPA’s exposure standard.

The department must also prove that the mountain provides a natural barrier between radioactive waste and the outside world — a hedge against radiation that might escape from the man-made containments. It’s the whole reason the department proposed burying waste in a mountain to begin with.

But opponents say water flowing through the mountain proves the mountain is no safeguard — and that Energy Department-designed canisters would be the only protection.

“It was no longer, ‘Is the site suitable,’ but ‘How can we engineer it to make it work?’ ” Loux said.

He said the issues remain today, and the Energy Department will rely on waste storage canisters and titanium drip shields to protect those canisters from water as the only safeguards.

Quality assurance

In 2005 and 2006, major Energy Department contractor Bechtel discovered disturbing e-mail messages between the department and scientists for the U.S. Geological Survey, a federal agency working on testing at Yucca.

The e-mail suggested that a USGS scientist had fabricated documentation of his work. He was studying how water flows through the mountain.

Opponents say the e-mail supports their main claim about the mountain’s safety.

The e-mail launched an investigation. Eventually, the Energy Department Inspector General ruled that scientists had not actually fabricated data that proved the mountain was safe, although their e-mail suggested they had.

Like a student who can solve a word problem correctly, but cannot explain how he arrived at the answer, the scientists had, essentially, not properly shown their work, the inspector found.

Recent history

On June 11, the Energy Department filed its application for a license to operate the repository. This is a major step, possibly the last hurdle standing in the way of approval.

The application is pending before the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, and the agency has asked for more information from the department about a federal environmental review of the project, including how ground water will move from Yucca to Death Valley.

Although the law gives the NRC three or four years to consider the application, observers say the proceedings could stretch out a decade or more. And the Energy Department says the soonest the site could be ready to receive waste is 2017.

Transportation

Should the NRC approve the license application, Yucca Mountain could well open for business. However the plan to ship containers of waste across the country certainly will generate a nationwide debate over transportation routes to the mountain. Communities take a dim view of nuclear waste shipments through their back yards.

The Energy Department plans to ship an average of 3,000 tons of waste to Yucca each year for 24 years from more than 120 sites across the country. The shipping plans will not be approved by the NRC, although the waste containers will.

Truck shipments must stay on interstate highways, but carriers — rather than the Energy Department — will determine the routes. The department has proposed a 320-mile rail spur from the Union Pacific main line from Caliente to Yucca.

Right now Nevada, the Energy Department and the Surface Transportation Board are wrangling over who has jurisdiction over the rail line. The department has applied to the transportation board to build the line, but unless it agrees to open it up to other users, the state may have jurisdiction over the line.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy