Thursday, May 15, 2008 | 3 a.m.

Audio Clip

- Hank Greenspun on being the first accredited reporter at the Nevada Test Site.

-

Audio Clip

- Hank Greenspun speaks about the Las Vegas Sun's role in helping individuals get gaming licenses.

-

Audio Clip

- Hank Greenspun on the changes he's witnessed in Las Vegas.

-

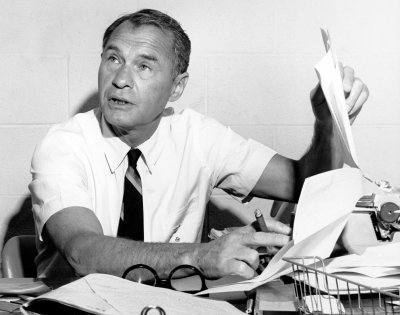

"Hank"

From starting the Las Vegas Sun in July 1950 to his multiple purchases of barren desert that would later become parts of Henderson and Green Valley, Brian Greenspun talks about the visionary that was his dad, Hank Greenspun and specifically, the vision that he had for Las Vegas as a community.

Growing Up Greenspun

Growing up in Las Vegas, and with Hank and Barbara Greenspun as his parents, Brian Greenspun didn't realize how different and unique his life was from other children that grew up around the same time as he, until he grew up and was told how special his experiences were. (Video produced in April 2008)

Where in the world was Hank Greenspun?

In early March of 1979, that was the question then Las Vegas SUN City Editor Chris Chrystal was asking around the newsroom. She had a question about a deadline story and Greenspun, who was a hands-on publisher, was nowhere to be found.

Late that afternoon, Chrystal was walking past the United Press International photo wire in the SUN newsroom and a picture from the machine made her do a double take.

The photo, taken earlier that day, featured four men walking along the Nile – Egyptian President Anwar Sadat, Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin, U.S. President Jimmy Carter, and an unidentified man.

The unidentified man? You guessed it. Peacemaker Hank.

“I didn’t even know Hank was in the Middle East because he was not one to blow his own horn,” Chrystal recalled. “He didn’t brag when he was about to take such trips and he didn’t brag about his accomplishments after them.

“I was never more proud to work for a newspaper where the publisher operated at such a level that he was able to assist the world’s leaders.”

Perhaps writer Rudyard Kipling best described Greenspun in his poem “If,” noting that to be a man you must be able to “walk with kings, nor lose the common touch.”

For there were many times that Greenspun would welcome needy single mothers into his office, then go into his “magic closet” and pull out toys to give to their children and reach into his pocket and give those families money.

“The SUN is what it is today because of Hank Greenspun, one of the greatest movers and shakers Nevada ever had,” Chrystal said.

“He had enormous vision for the state and moved in many circles, identifying with the so-called little guy or hobnobbing with kings.”

After strolling along the Nile with Sadat and Begin, Greenspun said in the March 9, 1979, SUN editions: “It is my belief that peace will be made and that both parties will sign (a treaty). And Jordan will come into the peace process as the signatories go down.

“And that in turn will mean Syria, a moderate state, will also join the peace settlement. And the Saudis will follow with their approval because they recognize that this is the only method for their own survival.”

Seventeen days later, Sadat and Begin set aside centuries old differences between their two nations and signed the historic Egypt-Israel peace treaty on the White House lawn.

Herman Milton Greenspun was born Aug. 27, 1909. But for a man who had the common touch that name was a bit too formal.

In September 1946, newspaper reporter James Fallon told Greenspun he reminded him of his old friend, baseball slugger Hank Greenberg. So he called Greenspun “Hank.”

“From that moment on, no one in Las Vegas called me anything else,” Greenspun wrote in his1966 autobiography, “Where I Stand — The Record of a Reckless Man.”

Greenspun at that time became publisher of “Las Vegas Life,” a slick, pocket-sized 5-cent magazine that chronicled Las Vegas’ nightlife. Fallon served as his executive editor.

Later, as publisher of the SUN, Greenspun would be as hard-hitting on political charlatans and other wrongdoers as Greenberg was on baseballs.

One of the last of the nation’s old-time publishers/crusaders, Greenspun was an undying voice for the little guy, battling ferociously against those powerful forces that would dare attempt to trample the common man’s rights.

In Greenspun’s July 23, 1989, obituary in the SUN, it was written: “Though his sky-blue eyes usually twinkled with mirth, compassion and caring, they could transform into flinty daggers of a fighter pilot ready to do battle.”

And the targets of his hard-charging style of journalism were some of the most powerful figures of his time, including Nevada political machine boss Sen. Pat McCarran, communist witch-hunter Sen. Joe McCarthy, and the Internal Revenue Service.

Born in Brooklyn, N.Y., Greenspun grew up in New Haven, Conn., where as a youngster, he had a paper route. Greenspun’s father was a Talmudic scholar and his mother a businesswoman.

Hank Greenspun graduated from St. John’s University with a law degree in 1934. He worked at the New York law firm where legendary New York City Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia was a partner.

1940s: After Army, Hank rolls into town

Greenspun enlisted in the Army in 1941 as a private, went to officers school and rose in ranks to a major.

During World War II, he served in Gen. George Patton’s Third Army, advancing through France and into Germany. He was decorated with the French Croix de Guerre for his courage at the Battle of Falaise Gap.

In 1944, while stationed in Ireland, awaiting the invasion of Europe, Greenspun met Barbara Joan Ritchie. They married in 1946. Today she is the publisher of the SUN.

In 1946, Greenspun drove to Las Vegas with his friend, Joe Smoot, who had visions of opening a horse racetrack with Greenspun. When that plan did not materialize, Greenspun published “Las Vegas Life.” But the weekly entertainment magazine failed to turn a profit.

To supplement his income, Greenspun became publicity agent for the Flamingo Hotel, run by mobster Benjamin “Bugsy” Siegel.

For two years, Greenspun wrote the Flamingo Chatter column for his future bitter rival, The Las Vegas Review-Journal. It was a far cry from the gut-ripping, muckraking columns Greenspun would become famous for at the SUN.

After leaving the Flamingo, shortly after Siegel was murdered in June 1947, Greenspun bought an interest in the Desert Inn and was a partner in the opening of radio station KRAM 920 AM in December 1947.

That same year, Greenspun became an important figure in international politics, specifically the creation of the state of Israel. Greenspun assisted the Haganah in its efforts to make Israel a homeland for the survivors of the Nazi holocaust.

With war on the horizon and Israel short on weapons, Greenspun bought machine guns and airplane parts in Hawaii and accompanied them through Mexico to ship to the Israeli freedom fighters fending off Arab forces.

The weapons got through, but Greenspun was caught and pleaded guilty to violating the Neutrality Act in 1950. He was fined $10,000 but received no prison time.

Greenspun called that chapter in his life one of his proudest because his cause was just and he played a role in the founding of Israel.

Upon Greenspun’s death from cancer on July 22, 1989, at age 79, former Israeli Prime Minister Shimon Peres called Greenspun “a hero of our country and a fighter for freedom.”

“(Greenspun was) a man of great spirit who fought with his mind and his soul; a man of great conviction and commitment,” Peres continued.

President John Kennedy pardoned Greenspun in 1961, restoring his civil rights. A year later, Greenspun ran for governor of Nevada as a Republican, but lost to in the primary.

While under U.S. government scrutiny for his efforts to help in the creation of Israel, Greenspun decided to get into the newspaper business.

During a 1949 labor dispute, the Review-Journal locked out its International Typographical Union workers, who formed their own newspaper, the Las Vegas Free Press. They met with Greenspun to discuss the purchase of the fledgling periodical.

1950s: Hank buys paper, renames it the SUN

Greenspun — with financial help from pioneer Las Vegas landowner, businessman, and Valley Bank founder Nate Mack — bought the paper for $104,000 from Community Printing and Publishing Co.

Greenspun paid $1,000 down for the paper, its flatbed press, and outstanding accounts. He renamed it the SUN on July 1, 1950. Over the next four decades he would voice his strong opinions in a front-page column called ‘‘Where I Stand.’’

At that time, the news media statewide kowtowed to powerful U.S. Sen. Pat McCarran, but Greenspun took up just cause against McCarran’s restrictive immigration bill — which Greenspun saw as an anti-Semitic measure to keep Eastern European Jews from immigrating to America.

A vindictive McCarran, in March 1952, ordered every local hotel-casino to pull their ads from the SUN. Greenspun reacted by keeping up his criticisms and later won a lawsuit over the boycott conspiracy.

McCarran even called in his good friend, communist hunter, McCarthy, to target Greenspun.

The SUN was one of the first newspapers to denounce the unfairness and lack of proof underlying McCarthy’s accusations of Communist influence.

During a visit to Las Vegas, McCarthy, speaking at the old War Memorial, where City Hall now stands, challenged Greenspun and his opinions.

During his speech, a fired-up McCarthy, meaning to call Greenspun an ex-convict for his Neutrality Act conviction, accidentally called him an ex-communist, causing an outraged Greenspun to storm the stage.

McCarthy fled from the stage as Greenspun shouted at him: “Show me your proof. Show me your proof.” The chant caught on and, from then on, wherever red-baiter McCarthy would go, people would shout at him, “Show me your proof.”

Greenspun’s columns exposing McCarthy as a demagogue during the height of McCarthyism, contributed to the senator’s downfall and disgrace.

“The series of columns on Joe McCarthy were the stuff legends are made of,” said Hank’s son, Brian Greenspun, who today is president and editor of the SUN.

“He (Hank Greenspun) used the type of tactics that McCarthy had used on others against McCarthy.”

In one column, Greenspun predicted that a victim of one of McCarthy’s actions would assassinate him. Greenspun recommended that, instead, the senator should beat the would-be killer to the punch and commit suicide.

Greenspun was indicted for publishing and mailing matter “tending to incite murder or assassination.” He was acquitted.

In another column, Greenspun labeled McCarthy “the queer that made Milwaukee famous.”

In a 1952 Where I Stand column, Greenspun wrote: “It is common talk among homosexuals in Milwaukee who rendezvous in the White Horse Inn that Senator Joe McCarthy has often engaged in homosexual activities.”

McCarthy considered filing a libel suit against Greenspun — but after being told by his attorneys that during a trial he would have to answer embarrassing questions under oath about his sexual activities — he dropped the matter.

Instead, in what many considered an effort to stop speculation that McCarthy was gay, McCarthy married his female secretary and they adopted a daughter.

Greenpun’s decision to out McCarthy was not meant to put down homosexuals for their lifestyle, but rather to demonstrate what hypocrites McCarthy, Cohn, and their cohorts were.

Cohn and McCarthy had targeted government officials and cultural leaders as not only Communists but also as homosexuals.

The two would sometimes use such sexual secrets to blackmail their targets into becoming government informants and betray their friends. Some of those men eventually killed themselves.

McCarthy, who was censured by the Senate in 1954, fell into alcoholic decline and died in 1957.

Greenspun’s newspaper also tackled local crooked politicians.

In 1954, Greenspun accused Clark County Sheriff Glenn Jones of having a financial interest in a brothel.

Jones sued so Greenspun hired an undercover detective to gather evidence. The agent secretly recorded conversations and discovered other politicians involved in scandalous behavior.

As a result, Lt. Gov. Cliff Jones resigned as Democratic national committeeman for Nevada.

In 1956, Greenspun started the SUN Youth Forum with the help of his longtime assistant Ruthe Deskin. They wanted to give young people a voice in the community.

The annual forum continues to this day, giving local high school juniors and seniors a platform each November to express their opinions on everything from teenage curfews, to abortion, to burning of the U.S. flag, or the current war.

Also in the 1950s, Greenspun ventured into other forms of media and started Las Vegas’ first television station, KLAS-TV Channel 8, which he later sold to reclusive billionaire Howard Hughes.

1960s: Desegregation, Hughes, social upheaval

In the 1960s, Greenspun began the process of bringing cable television to the Las Vegas Valley. His company was known as Community Cable TV and later Prime Cable. It began serving houses in 1980.

Years later, Brian Greenspun sold the local cable franchise for $1.3 billion to Cox Communications, which remains the largest provider of cable television in Southern Nevada.

On March 26, 1960, Greenspun, who had long called for equality and understanding among the races, got major hotels, local political leaders, and the local chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People together to consider Greenspun’s plan to put an end to segregation of Strip resorts.

The hotel operators agreed to end discrimination against blacks and allow minorities as guests. Political leaders agreed to form a race relations committee. The NAACP called off a planned march down the Strip and a nationwide boycott that could have severely damaged the local industry.

It was a major feather in Greenspun’s cap and a big story for the SUN because Las Vegas, which had been labeled “The Mississippi of the West,” became one of the first U.S. cities to do something about discriminatory practices. It would take the next 10 years for much of the rest of the country to advance so far.

On Thanksgiving in 1966, Greenspun arranged for industrialist Hughes to stay — and remain in seclusion — in a Desert Inn penthouse.

Hughes, with Greenspun’s help, subsequently bought the Desert Inn, other Strip resorts, and Southern Nevada property — bringing Las Vegas into the corporate age and creating a real estate empire that still thrives.

In 1968, Hank and one of his four children, Janie, attended the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago. While at a protest against the Vietnam War, they were chased and tear-gassed by police.

“The police went nuts,” Janie Greenspun-Gale said in a 2000 story for the newspaper’s 50th anniversary. “The next day, Dad was screaming at the Nevada delegates, telling them not to support the police because they were beating up children in the park.”

1970s: Watergate burglars target Greenspun

Greenspun’s relationship with Hughes and Hughes’ top aide and alter ego, Bob Maheu, landed Greenspun in the midst of the Watergate affair.

In the early 1970s, Nixon re-election campaign officials found it necessary to plan a little-known second burglary in addition to the infamous break-in of the Democratic National Committee at the Watergate Hotel.

The target was Greenspun’s safe at the Las Vegas SUN, then located on Highland Drive, which today is Martin L. King Boulevard.

Nixon’s cohorts believed that the safe contained copies of memos from Hughes to Maheu that spelled out the details of a campaign contribution from Hughes to Nixon that Nixon’s closest friend, Florida banker, Bebe Rebozo, had received.

While there was nothing wrong with that, the public disclosure of such a gift would prove troublesome for Nixon, who was skittish about anything linking him to Hughes.

That’s because Nixon believed that publicity from a questionable Hughes loan to one of Nixon’s brothers, Donald, in 1957 caused him to lose the presidency to Kennedy in 1960, and the race for governor of California two years later.

Hughes gave Doanld Nixon $250,000 to help him save his failing fast-food business. The loan, which was never repaid, was secured by a plot of land owned by the Nixon family in California worth only about $13,000 — hardly suitable collateral for a loan so large.

Also, Rebozo’s distribution of Hughes money may have been a violation of campaign spending laws.

On July 3, 1972, James McCord and four other burglars were arrested while placing electronic devices in the Democratic Party campaign offices at the Watergate.

Nixon’s people intended to wiretap the conversations of Democratic National Committee Chairman Larry O’Brien over concerns that O’Brien, who had served as Hughes’ Washington aide from late 1969 to early 1971, knew of the $100,000 Hughes/Rebozo transaction and would use it against Nixon.

On May 23, 1973, McCord admitted that his group, known as the “Plumbers,” had been involved in several covert activities, including a plot to crack Greenspun’s safe.

Government officials, including the Internal Revenue Service, demanded to see Greenspun’s documents. Greenspun took the case to court and got a ruling that the documents could remain private. They have never been released.

In the following excerpt from White House transcripts, Nixon discusses with his two top aides, Bob Halderman and John Ehrlichman the February 1972 break-in of Greenspun’s office:

Ehrlichman: McCord volunteered this Hank Greenspun thing, gratuitously apparently not …

Nixon: Can you tell me is that a serious thing? Did they really try to get into Hank Greenspun?

Ehrlichman: I guess they actually got in…

Nixon: What in the name of (expletive deleted) though has Hank Greenspun got with anything to do with (Attorney General John) Mitchell or anybody else?

Ehrlichman: Nothing. Well, now, Mitchell. Here’s — Hughes. …

Halderman: They busted his safe to get something out of it. Wasn’t that it? …

Actually, they managed to break into the office, but not the safe.

Despite the Donald Nixon-Hughes loan fiasco, Nixon, throughout the 1970s, continued to accept large donations from Hughes who received political favors in return.

Some believe that the payment to Rebozo in two $50,000 installments in 1969 and 1970 was intended to influence Nixon into getting the Justice Department to drop its objection to Hughes buying the Dunes Hotel.

Federal authorities at the time viewed Hughes’ acquisition of so many Las Vegas hotels as an anti-trust issue, where he was trying to monopolize the gaming industry.

Rebozo also was under great scrutiny. At first he told people he gave the money to Nixon’s secretary and Nixon’s brothers, Donald and Edward.

But such a claim could have led to Rebozo being charged with a campaign fund spending violation if it could be proved the money was not spent on the campaign.

As a result, when Rebozo went before the Watergate committee, he changed his story. Instead, he said he had put the Hughes money in his bank’s safety deposit box and apparently forgot it was there.

Investigators later examined the money and found it was mostly from the 1950s and tattered. The money Hughes gave Rebozo came from a casino cage of one of Hughes’ hotels and would have been newer and in better condition.

They concluded that the Hughes money likely had been given to others as Rebozo originally had said, and that the bills Rebozo found likely was replacement money that had come from a storage vault.

The Hughes-Rebozo transaction first came to light in 1971, seven months before the Watergate break in, when Greenspun attended a news conference in Porltand, Ore.

There, Greenspun asked Nixon Press Secretary Herb Klein: “What happened to the $100,000 in cash that went from Howard Hughes to Bebe Rebozo?

Klein went to Nixon attorney and confidant Herb Kalmbach, who in turn paid Greenspun a visit in Las Vegas to try to determine just how much Greenspun knew of the Hughes-Rebozo transaction.

He walked away with little info. Thus, the wheels were set in motion for the burglaries at the Watergate and the Las Vegas SUN offices.

Nixon did not help his own cause with the Hughes-Rebozo debacle when he fired special Watergate Prosecutor Archibald Cox, in part because Cox was prying into the $100,000 Hughes campaign gift.

After Cox was out of the way, a four-man team of investigators from the Senate Watergate Committee started looking into the Hughes gift — and potential cover-up of it — and soon after that Nixon’s house of cards collapsed.

Furthermore, Greenspun played a major role in shaping the history of Nevada politics. In 1970, Republican Lt. Gov. Ed Fike was heavily favored to beat Democratic upstart Mike O’Callaghan in the gubernatorial race.

Greenspun and his newspaper revealed that Fike, while in office, feathered his nest as an officer in a corporation that bought valuable land at a bargain price from the Colorado River Commission, a state agency.

Nationally syndicated columnist Jack Anderson picked up the story and Fike lost to O’Callaghan. When O’Callaghan finished his second term as governor, Greenspun hired him as chairman of — and a columnist for — the SUN, a post he held until his 2004 death.

In 1970, Greenspun also started the SUN Summer Camp Fund, which solicits money from the public to provide camp for children who couldn’t otherwise afford it. Thousands of children have benefited from the service.

Greenspun also is remembered as one of the valley’s top land developers.

Early on, he bought small parcels of Henderson land, eventually acquiring about 4,000 acres, before buying more than 4,000 additional acres from the city of Green Valley to build Southern Nevada’s first master-planned community.

In the April 2000 issue of Nevada Contractor magazine, the industry’s official publication, Greenspun was named one of Southern Nevada’s top five land developers of all time. The magazine selected him along with building giants Kirk Kerkorian, Del Webb, Irwin Molasky and Hughes.

Greenspun’s sprawling Green Valley residential and business development in Henderson began in 1973. It has significantly increased Henderson’s tax base, and Henderson also has become one of the fastest-growing cities in the United States.

For his years of service to the state and community, Greenspun was given an honorary Doctor of Humane Letters degree from UNLV in 1977.

1980s: Hank audits the IRS, becomes actor

Greenspun took on the IRS, exposing its abuses of taxpayers. In the 1980s, he even offered SUN subscribers the use of an attorney for free if they got called in for audits.

The free lawyer promotion cost the SUN $400,000 to $500,000.

Also, in the 1980s, Greenspun published the North Las Vegas SUN weekly newspaper.

He even tried his hand at acting, portraying a tough newspaper publisher in the 1985 film “Fever Pitch,” which starred Ryan O’Neal. The movie was shot in Las Vegas, including the SUN’s offices in the mid-1980s.

Greenspun formed The Greenspun Corporation to manage the family’s assets.

During the final months of his life in 1989, Greenspun helped negotiate a joint operating agreement by which the Review-Journal printed the SUN and distributed it. The SUN retained independent editorial control.

The SUN operated as an afternoon daily from 1990 until October 2005, when the joint operating agreement was amended to have the SUN delivered in the morning with the Review-Journal and enjoy the same circulation.

1990s: Hank’s estate benefits UNLV

Greenspun and his family played major roles in the growth of UNLV. The Greenspun College of Urban Affairs and the Greenspun School of Communication carry on his legacy.

The UNLV College of Urban Affairs, created in 1996, included the Hank Greenspun School of Communications, the School of Social Work and the departments of environmental studies, leisure studies, counseling, and criminal justice.

With a $1.7 million gift from the Greenspun family later that year, the college adopted its current name, the Greenspun College of Urban Affairs.

In 2005, the Hank Greenspun school split into two units, the Hank Greenspun School of Journalism and Media Studies and the department of communication studies.

The college now offers two doctoral programs — public affairs and environmental studies — in addition to eight bachelor’s and seven master’s degrees.

In January 2007, the Greenspun College of Urban Affairs broke ground for the $94 million, five-story Greenspun Hall, funded by the state and the Greenspun family. The college expects to move into the building in 2008.

Greenspun won numerous civic awards and honors, including the naming of Jewish War Veterans Post 30 in northwest Las Vegas in his honor in October 1996, the year the JWV turned 100.

Also in 1996, the JWV began its annual Hank Greenspun Distinguished Citizen Award. Former two-term Nevada governor and longtime SUN Executive Editor Mike O’Callaghan was the first recipient of the honor.

Explore Las Vegas’ past and present

Explore Las Vegas’ past and present Boomtown: The Story Behind Sin City

Boomtown: The Story Behind Sin City Neon Boneyard: A 360° look

Neon Boneyard: A 360° look Mob Ties: See the connections

Mob Ties: See the connections Implosions: Classic casinos crumble

Implosions: Classic casinos crumble