MGM Mirage’s CityCenter project includes a casino and six high-rise buildings, all to open in 2009. Four men have died in accidents on the site since work began.

Monday, March 31, 2008 | 2 a.m.

The case of Willie Pelayo

General laborer foreman Willie Pelayo rode a malfunctioning buggy into an elevator shaft and was killed at Trump Dec. 5, 2006. OSHA initiated a two-month long investigation and issued a report that involved extensive documentation, including photographs and a complete evaluation of the buggy. OSHA issued his employer, Perini, three violations, and then held an informal conference where an OSHA administrator, in a hand-written note, said that Perini had sacrificed safety for speed. Then OSHA issued an amended list of violations that reduced fines against Perini.

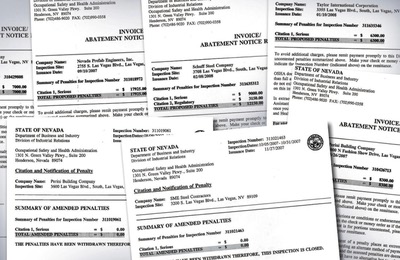

Here are some of the documents involved in the case:

Hundreds of construction workers signed a 10-foot long memorial poster for the family of Harold Billingsley after the 46-year-old ironworker plunged to his death at CityCenter last year.

Four months later, on a night in February, relatives unrolled the poster at the home of his sister, Monique Cole, and her husband. Cole placed Billingsley’s brown leather boots and sticker-covered construction helmet on the kitchen table. The family had gathered to talk to a reporter.

“It feels like they rendered my brother’s life valueless,” Cole said, crying as she recalled the Nevada OSHA conclusion that Billingsley’s employer bore no responsibility for his death. “You assume all the right things are in place until you’re faced with it.”

Nevada Occupational Safety and Health Administration conducted a one-month investigation after Billingsley fell 59 feet to his death. The conclusion: SME Steel Contractors, Billingsley’s employer, had violated safety laws by leaving the hole in an unfinished temporary floor. Also, his safety harness wasn’t working properly.

“The foreman was on site, aware of the progress of the work and the area where the employee was working,” OSHA inspectors wrote. “With reasonable diligence the hazard could have been detected and prevented.”

Another thing could possibly have saved his life. OSHA regulations call for a net or a temporary floor every two floors below employees working on steel erection. Billingsley, however, plummeted nearly twice that far because neither was in place.

OSHA issued three citations carrying fines totaling $13,500. But then SME met privately with the agency in what’s known as an informal conference. No family was invited. Billingsley’s union local did not send a representative.

Without offering any additional documented evidence, the company blamed Billingsley. He wasn’t supposed to be in the area, it said, contradicting the findings of the investigation.

OSHA withdrew the citations.

Billingsley now bore sole responsibility for his death.

Cole was mystified. “The everyday Joe Carpenter is not aware of how fallible the system is,” she said.

Her husband, George, sat at the kitchen table of their sprawling Sunrise Mountain home thumbing through an OSHA report he had been given by the reporter. A retired ironworker, he once owned a subcontracting business that had been cited by OSHA.

Cole knew the trick, he said. Blame the worker.

If someone dies at a Nevada construction site and OSHA points the finger at poor safety procedures, the agency often will relent during informal sessions with the contractors, he said.

Then he added: He knew all along that the agency would clear SME.

His wife looked up in disbelief. If you knew the fines were going to be dismissed, she asked, why didn’t you tell me?

“I knew it would upset you,” he said.

•••

A Sun examination of OSHA accident documents related to nine recent construction fatalities on the Strip shows that investigators found serious safety violations in the cases, but the agency often did not follow up with aggressive enforcement. Instead, after meeting privately with contractors, the agency withdrew or reduced fines.

Government and private safety experts outside of Nevada as well as the families of the accident victims told the Sun they are surprised and disturbed by OSHA’s conduct after the fatalities.

Frank Strasheim, a former regional administrator in the federal OSHA office in San Francisco, and other experts say they have seen many citations removed by federal and state OSHA offices elsewhere — but rarely in cases involving deaths.

“My rule of thumb has always been that you hold the line on a fatality,” Strasheim said. “A fatality is the worst possible thing.”

If employers offer statements that contradict elements of the initial investigation, OSHA administrators should reopen the investigation rather than quickly overturn citations, he said. Strasheim and others said that a pattern withdrawing citations could indicate that Nevada OSHA is either doing a bad job in its initial investigations, or is overusing a provision in OSHA laws that allows the agency to reverse itself if it thinks the findings won’t hold up under review.

Here is how Nevada OSHA handled the eight cases in addition to Billingsley:

• Harvey Englander, 65, a veteran operating engineer and employee of construction giant Perini Building Company Inc., who died Aug. 9, 2007, when struck by the counterweight of a manlift, or elevator, at CityCenter.

OSHA found that Perini violated six safety laws.

The findings were withdrawn.

• Angel Hernandez and Bobby Lee Tohannie, carpenters killed Feb. 6, 2007, when crushed inside an elevator shaft at CityCenter by 7,300-pound structures that support poured concrete.

OSHA found the site’s general contractor, Perini, did not make sure the forms were properly secured and did not train employees in the proper removal of the forms. The agency fined Perini $14,000.

At an informal conference between OSHA and Perini, an OSHA administrator withdrew one violation and left the other intact, for a total fine of $7,000.

• Isidro “Willie” Pelayo, the worker killed when a buggy jerked and threw him down an elevator shaft at Trump on Dec. 5, 2006.

OSHA found that Perini had failed to train employees in the use of buggies and had not maintained them properly or checked to see whether they were safe. Three violations carried $18,900 in total fines. At the informal conference, OSHA agreed to withdraw one fine and downgrade another, reducing fines to $8,300.

• Michael Hanson, a laborer working for Taylor International Corp. at Palazzo, who was killed when a piece of a concrete slab raised by a forklift struck him in the head on Nov. 26, 2007. The investigation found that using the forklift to remove concrete was common at the Palazzo even though that use is forbidden by the forklift manufacturer and by OSHA. The agency found one violation and fined Taylor $6,300.

At the informal conference, OSHA reduced the fine to $3,780.

• Michael Taylor, 58, a Perini safety engineer at Cosmopolitan. He died Jan. 14, 2008 after apparently falling five floors when a corner iron post that helped hold up a guardrail system collapsed.

In the investigation, OSHA found that Reliable Steel, a subcontractor, had not replaced key support pieces and hadn’t properly welded the posts. It was inevitable the post would malfunction in time, the investigator wrote. OSHA also found that Reliable Steel was underreporting injuries in its required injury logs. The agency issued four citations for fines totaling $2,850.

Reliable Steel has contested the citations, and OSHA will hold the informal conference in April.

• Norvin Tsosie, 36, who fell from a wall at Fontainebleau on Aug. 2, 2007.

OSHA fined his employer, Nevada Prefab Engineers, $17,925 for 10 violations for allowing workers to use makeshift materials that hadn’t been tested, and for not making sure that safety harnesses were properly attached.

The subcontractor did not contest the findings.

• David Rabun Jr., 30, an ironworker at Cosmopolitan. He fell four floors on Nov. 27, 2007, while replacing bolts in a steel beam inside an elevator shaft.

OSHA found that Rabun’s employer, Schuff Steel, had violated six safety laws, including not making sure the steel he was working on was secure, and not putting a net or decking underneath him. Schuff Steel was asked to pay $12,150.

OSHA held an informal conference with Schuff on Feb. 27. That came after the Sun repeatedly asked the agency about its handling of earlier cases and after federal OSHA officials, responding to newspaper inquiries, expressed dismay to the Sun regarding the state agency’s actions.

For the first time involving a Strip fatality during the current building boom, OSHA stood by the original findings and did not make a deal with the employer. The case will most likely be appealed to an OSHA review panel.

So why would Nevada OSHA remove or reduce citations following the other fatalities?

In some states, OSHA departments favor easy, expedient resolutions, said Celeste Monforton, a lecturer at George Washington University’s School of Public Health and Health Services, who used to work at federal OSHA.

“They would rather make the thing go away,” Monforton said. “If you can make it go away by an informal settlement, where the company comes in and says we’re going to put in a good safety program and do all these things, for the sake of bureaucratic expediency OSHA might rather close the case and go on to the next investigation. That’s how these things go away.”

When a case is sent to a review board, the company isn’t required to immediately correct safety problems at the work site. For that reason some OSHAs try to settle cases so glaring safety problems are cleaned up quickly, Monforton and other experts say.

But that doesn’t appear to have been as much of an issue here. In Billingsley’s case, for example, all of the specific violations cited by OSHA had been corrected even before the citations were issued.

Greg McClelland, a representative of the Ironworkers Labor Management Cooperative Trust, said the pattern in Nevada indicates that OSHA is trying to work cooperatively with employers to improve safety.

“A lot of people think OSHA needs to be cracking heads and making people pay, but the problem with that is that it nurtures an adversarial relationship, and you get more resistance from companies,” McClelland said. “It’s better if companies buy in to the program.”

A sign that Nevada OSHA may have adopted that approach is the existence of a safety expert in OSHA’s consultation and training division — outside of the enforcement process — working to help Perini evaluate and correct safety problems at CityCenter, according to a person who works for the agency and was told not to speak to the media.

Another factor that may be at work in Nevada is limited resources.

If employers contest a citation and OSHA doesn’t work out a settlement during an informal conference, the agency has to either reopen the investigation or defend the findings before a review panel. That takes time and staff — two things in short supply at Nevada OSHA.

A paucity of safety engineers in the state and nationally has made it tough for the agency to retain investigators, who are quickly lured by more lucrative jobs as on-site safety experts at construction companies, including on the Strip.

Elisabeth Shurtleff, spokeswoman for Nevada OSHA’s parent agency, the Business and Industry Department, said that for the Las Vegas area, it has 25 budgeted positions for inspectors. Five of those are vacant.

The number of inspector positions for Las Vegas did not increase from 2001 to 2007, even though the number of employees in all occupations grew by 200,000 to 927,000, and most of the agency’s funding comes from workers’ compensation assessments, not general taxes, which means employers pay the costs.

The 20 Las Vegas area inspectors make random workplace visits and inspect a site every time someone calls to complain about a possible infraction, in addition to conducting investigations of big accidents. Even if all the positions were filled, OSHA would need 27 years to pay a single visit to each workplace in the state, according to the AFL-CIO.

Perini Building Co. alone has kept OSHA pretty busy. The contractor was inspected 25 times in 2006 and 2007 on its large casino projects in Las Vegas. OSHA issued the company citations for 38 violations, 17 of which were withdrawn at informal conferences.

As small as the Nevada staff is, however, an AFL-CIO nationwide study found that last year Nevada OSHA had done more inspections per workplace than any state except Oregon.

•••

Veteran operating engineer Harvey Englander, 65, had decided CityCenter would be his last job. His wife, Susan, said he spoke to her often about how he and his co-workers spotted safety violations but were too intimidated by their prickly foreman to speak up.

He decided he would work only until Susan retired from her job as a respiratory therapist.

Last August, he was lubricating a cage that carries workers between the ground and upper floors. The lift was one of two that worked in tandem, each off a counterweight. As he worked, the adjoining lift traveled up to pick up workers and its counterweight came down, killing Englander.

He wasn’t supposed to be the one greasing the machinery, Susan said in an interview. But his boss had come down hard on workers after being told that it wasn’t being lubricated often enough. Englander started greasing it daily — more than it required.

OSHA investigator Nicholas La Fronz spent two months after Englander’s death interviewing employees and Perini bosses, and reviewing the company’s training manuals and videotapes. La Fronz found a variety of safety problems on the site that he thought contributed to the death:

• Manufacturer safety rules posted on the machinery say passengers shouldn’t be transported on the lift until after a daily inspection is complete. But operators of the lift told La Fronz, “When it’s busy you have to just get started running the lift because there are a lot of people waiting, and you do your inspection later in the shift when things slow down.”

• Larry Tucker, the operating foreman, said he told workers that only the car being greased needed to be shut down and locked out. The manufacturer’s safety rules, however, require locking out both cars when either lift is being greased to eliminate any chance they will be put to use.

• Englander’s employer knew he was greasing the lift too often.

• Workers did not know the lift was to be locked with a padlock while being greased.

La Fronz found six violations, all rated “serious.” Three carried the maximum penalty of $7,000. Three others did not call for fines.

OSHA safety manager Jimmie Garrett signed the findings and sent them to Perini.

On Nov. 28, one month after the original citations were issued, three Perini safety professionals and a Perini attorney met with La Fronz and Garrett in an informal conference.

No one from Englander’s family was invited. The operating engineers union did not send a representative.

The $21,000 in fines wouldn’t have been the most pressing issue for Perini, a company that made $4.6 billion in revenue last year.

Contractors fight citations because fines can become hefty if the violations are repeated, because they want to have a clean record when applying for new jobs and because insurance companies will balk if too many citations pile up, said Frank Keres, a construction risk consultant who works with insurance companies, contractors and owners.

At the meeting, Perini argued:

• One of the citations referenced the wrong OSHA law.

• The company had trained Englander on the safe operation of the manlift, and had demonstrated that to the inspector. (La Fronz had included in his report documentation showing the company had completed a checklist of training topics but had concluded it was not adequate.)

• The rules were posted in the cab of the car. (La Fronz documented that but dismissed it as insufficient.)

After the conference, Garrett wrote a report placing all responsibility for the death on Englander. Although he had signed off on La Fronz’s findings, Garrett now wrote: “The deceased did not follow the instruction posted in the personnel hoist. No one was aware that the employee had decided to do maintenance on the personnel lift while the other personnel lift was operating. This error resulted in the employee’s death.”

Garrett removed all citations. The report contained no supplemental documentation to support the decision.

Garrett refused to answer the Sun’s questions about the informal conference. La Fronz did not respond to phone messages.

OSHA spokeswoman Shurtleff refused to allow the Sun to interview anyone at the agency, citing its policy.

Construction safety experts say OSHA’s original case against the company could have been upheld.

“If the regulation requires a lockout of the machinery, then the company is responsible for that,” said Steven Hecker, a senior lecturer in environmental and occupational health services at the University of Washington who has written extensively on construction safety.

Even if Perini had posted rules inside the manlift, “OSHA should have been able to say, ‘You clearly didn’t ensure that your procedures were adequately followed,’ ” Hecker said. “This should not have been grounds for voiding a citation like that.”

Dale Kavanaugh, a federal OSHA administrator in Seattle, said his department takes a conservative approach when fatalities are involved.

“How do you explain to a widow that it’s her husband’s fault that he’s dead?” Kavanaugh said. “We don’t want to be in that position.”

•••

Six months after her husband died, Susan Englander sat on a couch surrounded by antiques she and her husband had collected on weekends.

Englander clutched a small book in which she had scribbled the names and numbers of lawyers, Harvey’s co-workers and anyone else she was in touch with after the accident. She had to hire a lawyer to speed up the delivery of her workers’ compensation benefits, which come to about $1,500 a month for life, unless she remarries.

Perini representatives — she calls them “the pencil pushers” — came by right after Harvey died, and their business cards are stapled in the book.

Midway through the investigation, Susan sensed OSHA wouldn’t do enough. The case inspector told her there would be a meeting where the company could contest citations, outside the formal appeals process.

“I said, ‘Wait a minute. Either they did it or they didn’t do it. How can you change things?’ He said, ‘That’s just the process.’ ”

So Englander tried another tack. She thought she could make Perini or another contractor on site pay for unsafe conditions by suing them.

No lawyer would take her case.

Here’s why: Workers’ compensation law requires employers to pay dependents of killed workers a portion of their salaries. In exchange, the law shields employers from liability on the work site.

Nothing short of proving beyond a reasonable doubt that an employer targeted the employee and wanted him dead will usually cut it in state courts, said Nevada lawyer Craig Kenny, an expert in workplace accident law.

“Basically, you have to prove that it was an intentional act, that the supervisor came and hit them over the head with a shovel,” Kenny said.

Some lawyers instead go after manufacturers, who are not shielded by workers’ compensation laws.

The widow of Willie Pelayo, the worker killed when a buggy jerked and threw him down an elevator shaft at Trump, sued Perini for creating an unsafe workplace. A court threw it out. So she has sued the manufacturer of the buggy, Miller Spreader.

But both Englander’s and Billingsley’s families say that suing a manufacturer wouldn’t accomplish what they want — to force contractors to make workplaces safer.

Englander is resigned. “It seemed a waste of my emotions,” she said. “I have to move on. It just doesn’t seem that there’s any way to reach these people.”

Billingsley’s sister, Monique Cole, called many personal injury lawyers in the phone book before she found someone who would even agree to meet with her.

“Lawyers tried to tell us that we should say it was a manufacturer’s problem, but that has nothing to do with what this issue is about,” Cole said. “We want someone on the site to take responsibility. We want to make sure his death wasn’t in vain.”

After Billingsley died, Cole received a check in the mail from SME’s workers’ compensation carrier, AIG, to cover funeral expenses. Billingsley had no dependents to receive additional benefits. The check was for $3,942.29.

•••

Fred Toomey is on the same mission as Cole and Englander.

Toomey was the business agent for the Ironworkers Local 433 Las Vegas branch for 15 years in the 1970s and ’80s. He said when he ran the union here, he often shut down projects or threatened to shut them down over safety violations. He thinks unions could be doing more to find and fix safety problems on work sites.

After he heard that Billingsley fell 59 feet with nothing underneath him, Toomey rushed from his home in Pahrump to the union hall.

“I said, ‘What in the hell is going on?’ ”

He said Chuck Lenhart, the current business agent, said, “It’s the man’s fault.”

“He took me on the job and we walked around,” Toomey said. “We went up 60 feet. Chuck says, ‘See, this is his fault. He should have tied off to this cable, and then he wouldn’t have fallen.’

“I said, ‘Wait just a minute. This is 60 feet up in the air ... It’s supposed to be completely decked over every 30 feet.”

OSHA regulations call for decking every two stories or 30 feet, whichever is shorter, as a precaution against falls. (Toomey once fell and was saved by decking 30 feet below.)

In 2002 federal OSHA issued a new interpretation. A violation would be considered minor as long as workers are required to use their safety harnesses.

Later that day, Toomey fired off a letter to the union that chastised union foremen and superintendents for not keeping the workplace safe. He also said union stewards and other workers should be more active in reporting safety violations and demanding they are fixed.

Lenhart dismisses the complaints. In an interview in his office a few months later, Lenhart repeated what he had told Toomey the day Billingsley died.

The accidents that have befallen ironworkers are the unfortunate result of mistakes by the men who died, Lenhart said.

“As far as I can see everything looks good out there,” he said. “My contractors, they’re performing in a workmanship-like manner. What you see is just a result of the sheer number of man-hours.”

Lenhart also described Toomey’s concerns as the those of someone who is out of touch.

“The way he did things and way things should be done are two different things,” Lenhart said. “This is not 1985, and things in the industry have gotten safer and we have a lot more people working in the area.”

Asked about the union local’s decision not to attend the informal conferences between Nevada OSHA and contractors, Lenhart said: “That’s between OSHA and the company. We’ve never been invited.”

In fact, unions can join the conferences.

OSHA regulations require employers to post notification of the proceedings in the workplace, which should allow union stewards to find out about them, and employee representatives are allowed to attend the conferences.

Some OSHA offices do not strongly enforce that rule, said Seminario of the AFL-CIO.

But she recommends unions make the effort to find out about and attend informal conferences because, she said, they can offer an important balance against the employer perspective.

“They’ll definitely provide more oversight, particularly in a fatality case,” Seminario said. “I think you would end up with a stronger input and insistence on maintaining (the citations). You would get penalties that at some level are commensurate with the violations and will provide some deterrent from future violations.”

For example, when Peter Dooley, now a workplace safety consultant, served as a health and safety expert for the United Auto Workers in Michigan, he attended many informal conferences.

“Anytime a worker died, we would have a separate investigation that would be complementary to what OSHA did, but much broader and much more comprehensive,” Dooley said.

“From the union perspective, we would want to know why was this workplace being managed in such a way that could allow something like this to happen, and what could have been done to prevent this,” he said.

“The company has to know there’s going to be challenges to just a one-sided story, and it sends the message to OSHA that they have to be listening to both sides.”

Many of the building trade unions in Las Vegas say they’re trying to create safer work sites outside of government regulation and without disrupting their cooperative relationship with employers.

•••

When Harold Billingsley’s brother-in-law owned the subcontracting business Uriah Enterprises, he happily took work at places such as Circus Circus, Luxor and Monte Carlo. Like everyone else, George Cole said, he would forego some safety measures in the rush to finish a project on time and avoid the penalty for being late.

“You would get complacent about safety rules, because the job gets put on a schedule and no matter what happens you have to get it done,” he recalled last month in the interview at his home. “So you would drive men harder. You take shortcuts. Everyone turns a blind eye.”

Until someone got hurt, everyone was happily working and making good money.

When there was an accident or some other infraction, Cole negotiated with OSHA to whittle down the citation as far as he could.

“You work each one of those citations, work them until they’re gone, and what kind of incentive is that to change your practices?” Cole said. “I saved our company lots of money. I just kept fighting them.”

In the early 1990s, Cole encouraged Billingsley to quit his job as a bus mechanic and go into ironwork. Rusty was an “adrenaline junkie,” Cole said. So a profession that involved balancing on high beams was a good fit, and he started working for Cole.

Billingsley started last year at the Cosmopolitan, sometimes working as much as 70 hours a week. He skipped out of the usual family gatherings because of work.

A few weeks before he died, Billingsley stopped by the Coles’ house while he was out walking his dogs, and he and George Cole shared beers outside. He told Cole that he had quit Cosmopolitan to work at CityCenter.

His job at Cosmopolitan — to precisely align support columns — was just a little scary, a little dicey. He didn’t feel safe, Cole said Billingsley told him.

On Oct. 5, Cole received a phone call from a buddy working a crane at CityCenter. The friend had heard Billingsley’s name over the radio.

Cole rushed to the site and waited until he heard the news. Then he made the difficult call to his wife.

And his perspective shifted.

Four months later, as he sat with his wife Monique, he heard her say that she had always assumed companies such as the ones her husband owned or her brother worked for would be punished for safety shortcuts that endangered workers.

George Cole looked across the kitchen table and the couple locked eyes.

“Yeah, I see the irony now,” he said.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy