Monday, March 24, 2008 | 2 a.m.

When a coroner daydreams, it isn’t pretty.

Mike Murphy has a regular morning routine: He spends an hour eating a breakfast sandwich and reading the paper in his pajamas before he changes into one of his sharp suits, drives to work in his black beast of a county car, parks in his special spot, and walks through a back door of a low building and into the lively world of Vegas’ dead.

When the coroner catches a few minutes, he’ll go eat an omelette at a nearby cafe (he always brings a muffin back for his secretary), or dust the photographs on his desk, most of which feature the bald man and his blushing bride.

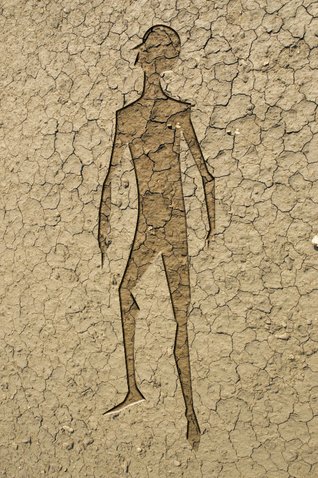

And when he’s really alone with his thoughts, when he’s snapping on the 10,000th pair of latex gloves, or on hold waiting for someone important to pick up, the coroner might spend a few seconds thinking about bodies rotting in the Clark County desert. Dozens of them, laid out bare, or locked in cars, or buried in refrigerators 6 feet underground, slowly decomposing or bleaching into bone.

When a coroner daydreams, it’s of body farms.

This is what they’re casually called: body farms. Tracts of land where donated bodies are left exposed to the elements and studied by forensic scientists: academics who catalog the progression of putrefaction, bugs’ assault on the body, the ebb and flow of flesh.

Two body farms currently operate in the United States. The oldest, and most infamous, is in Knoxville, at the University of Tennessee, where researchers have been studying bodies on a patch of razor-wired university land since 1971. The second opened three years ago in Cullowhee, N.C., at Western Carolina University. A third is to open in Texas this spring, at the Forensic Anthropology Center of Texas State University.

Las Vegas was going to have one, too — a sprawling multiacre desert site where local forensic students could chart a body’s progress the way any doctor follows a patient, until his patient is no more. The body farm idea first formally emerged in 2003, during a confluence of two different but influential cultural developments: America’s growing fascination with TV shows that dramatize crime scene investigations, and America’s decision to invade Iraq.

The CSI connection is clear. Dozens of national universities were exploring forensic science programs in the hope they might capture the academic interests of TV gore junkies. The Iraq connection is less obvious and far darker. Clark County’s terrain mirrors that of the scorched-earth Middle East, said Metro Police Lt. Tom Monahan, who was presiding over Metro’s homicide section when the idea first came to him and Murphy. The hope was that by studying the science of death in Las Vegas, he said, we could understand it better on the battlefield.

•••

Beef jerky. That’s Murphy’s favorite metaphor for describing what happens to a body left in Nevada’s arid climate. Imagine a steak left to dehydrate. As water is leached from the meat, the protein shrivels and toughens. The same thing happens in Vegas. Bodies are basically mummified in the heat.

In Tennessee and North Carolina, the only other states with operational body farms, decomposition is different. In moist environments, Murphy says, skin has a tendency to be eaten by “critters” as it slowly sloughs off, waterlogged. Scientists in the South have scrutinized these changes and gathered volumes of information for medical examiners and crime scene technicians to apply in the field, Tennessee body farm director Dr. Richard Jantz said. University faculty from several disciplines use the farm to study DNA degradation, the biochemistry of the decomposing body and phenomena that can help estimate time of death.

More than 300 people have donated their bodies to the Tennessee farm, and there’s never a shortage of applicants, Jantz said. The bodies slowly stock the school’s extensive collection of modern American skeletons. Complete sets of bones with documented medical histories, Jantz said. This information has helped the university study an altogether different, yet pressing, medical concern: obesity. More and more of the bodies Tennessee receives are overweight.

More recently, university scholars used bones from those bodies to develop the first sex-specific knee prosthesis.

Studying the systems of death is really just another way of understanding life, Jantz said. For this reason, he said, the Knoxville farm “has evolved into a source of civic pride.”

Our understanding of death and degradation in arid climates like Las Vegas’, however, is anecdotal, he said. It has never been closely, systematically studied.

This is in part because plans for the Las Vegas body farm faded like one of Murphy’s daydreams — slowly, so that all that remains is the skeleton of an idea, one that occasionally dances across the desks of people like Murphy and Monahan, when they pause to put more sugar in their coffee and stir themselves into seconds of rumination.

“It’s certainly alive in our subconscious,” Murphy said.

•••

The plan was to use a large and craggy swath of Metro land sandwiched between the department’s firing range and Nellis Air Force Base. The land included lower basins and higher rock outcroppings that would allow students to study decomposition at varying altitudes. Different bugs in different kinds of bodies, and people of different ages in different states of decay.

Several entities were involved in the planning: the coroner’s office, the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology (that Iraq connection again), UNLV, the College of Southern Nevada. At the time, Las Vegas would have had only the second body farm in the country, and it would have been far, far larger than Tennessee’s 3-acre facility, Murphy said. Fifteen acres, maybe 20.

They talked of training new crime scene technicians on the land, exposing them to actual bodies instead of the usual mock-ups, training them to deal with the real smells and the real sights, he said. Firefighters learn by setting buildings on fire and putting them out. Doctors learn by poking and prodding volunteer patients. Why couldn’t future forensic pathologists learn by looking at actual bodies, actually outside?

All of the dry West would have looked to Las Vegas for its forensic findings.

“There is kind of an eew or yuck factor to it, but I think the most important part to remember is, if it makes a crime scene analyst better with their job, they may, in fact, solve a crime quicker. And to keep that person who committed a crime from committing another one, that in and of itself is worth it,” Murphy said. “If it solves an unsolved case, if it provides a family resolution, that, in and of itself, is worth it.”

Worth it, but too expensive.

The body farm died under a pile of dollar bills. About half a million dollar bills. Maybe a little more, and maybe a little less. Just enough money to hire the necessary security, to fence off the land, to buy a double-wide trailer and a backhoe to move dirt around. Together, the groups approached the Department of Justice, and couldn’t find a grant or a person to give them money. The schools couldn’t afford to float the entire project either, and the county is always loath to spend money.

The project faded, but the bodies are still haunting Murphy, and almost everybody who was part of the project.

Former senator and forensic dentistry expert Ray Rawson was part of the body farm dream. He was heartbroken when it fell through the cracks, but still crosses his fingers that the project will be revived.

Metro Capt. Stavros Anthony, a Nevada higher education system regent, went to a few of the body farm meetings but doesn’t remember why the project died — only that he thought it was a great idea then, and does now.

Monahan is now head of Metro’s Homeland Security Division — he thinks about the body farm from time to time, when he’s not worrying about ricin or whatever top-secret security matters crowd the head of a high-profile lieutenant.

Jantz in Tennessee says he wants it to happen. He’s eager for a body farm he can check his own findings against.

And Murphy says the body farm will come to be. It’s just a matter of finding the right grant, or the right time, or the right pocket to pick.

“Its one of those things you always keep in the back of your mind. Shoulda, coulda, woulda,” he said. “But I’m the eternal optimist. I believe there is a very strong possibility that it could happen. That it will happen.”

In his daydreams, he must see that stretch of land baking still, waiting for someone to bring it back to life with a world of death.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy