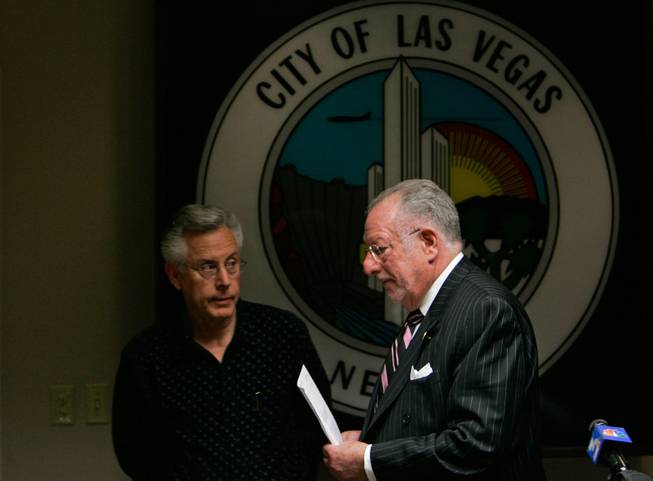

Las Vegas City Councilman Gary Reese, left, and Mayor Oscar Goodman attend a news conference on the decision to revoke the Endoscopy Center of Southern Nevada’s license.

Tuesday, March 4, 2008 | 2 a.m.

Hepatitis Hearing

Las Vegas mayor Oscar Goodman discusses the upheld suspension of the Endoscopy Center of Southern Nevada's business license, which was revoked last Friday after 40,000 patients learned they might have possibly contracted diseases from unsafe medical practices at the clinic.

Sun Archives

- How hepatitis probe led to clinic (3-2-2008)

- City shuts clinic, with harsh words for owners (3-1-2008)

- Hepatitis scare malpractice cases already in works (2-29-2008)

- On death’s door (2-29-2008)

- Large-scale hepatitis alert has no precedent (2-29-2008)

Beyond the Sun

The widespread outrage surrounding the clinic that put 40,000 people at risk of infection with hepatitis B and C and HIV has focused on several questions.

The answers may not satisfy the gut-level cries for justice.

Virtually everyone in Las Vegas knows someone who needs to be tested for infectious diseases because of the injection practices at the Endoscopy Center of Southern Nevada, where improperly shared vials of anesthetic medicine were tainted with patients’ blood and then used on other patients.

Health officials say six patients became infected with hepatitis C, and many more are at risk. So as the story unfolds and thousands of valley residents await the results of blood tests, here are answers to three of the most commonly asked questions.

How long did investigators observe nurses engaging in dangerous injection practices before they stopped them?

It was an unfolding discovery process.

Brian Labus, senior epidemiologist for the Southern Nevada Health District, said that after a day of reviewing charts, investigators on the morning of Jan. 11 began observing the nurses and doctors conducting various procedures, taking note of every step of the process to determine any instance where disease could have been transmitted. They didn’t know exactly what they were looking for.

Among the practices they observed were how the certified nurse anesthetists were using syringes and drawing medicine from the vials. During lunch they discussed among themselves what they saw, and it became clear in hindsight that the injection practices were the probable cause of the outbreak.

After lunch the team ordered the staff to no longer draw anesthetics from a vial with a previously used syringe — which could contain back-flow of a patient’s blood. The staff also was instructed to not share vials among patients because of the fear the anesthetic could be contaminated by the infected blood of previous patients. Later, nurses confirmed to investigators that they had been reusing syringes and vials, saying they’d been doing what they were told to do.

Why did it take so long to alert the public?

The health investigators’ mid-January visit to the clinic lasted about a week, but that was not the end of the probe. Health officials sent to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention blood samples from clinic employees to make sure they weren’t the source of the outbreak, and samples from the infected patients to determine if the disease could be genetically linked to the clinic.

It took about three weeks to get results, which confirmed the connection between the outbreak and the clinic.

Investigators also made repeated visits to the clinic to examine records, talked to health officials in other states who had to do similar patient notifications, and crafted a letter to patients and literature to inform the public. During that time the clinic was open for business, having corrected the deficiencies.

On Feb. 7 health officials requested a contact list for the clinic’s patients in the past four years so they could be notified of the need to be tested. It took until Feb. 22 to get the mailing list of 40,000 patients from the Endoscopy Center. The announcement came five days later.

The letters were mailed Wednesday and Thursday.

If what has been reported by officials is true, why didn’t any clinic workers blow the whistle on how the clinic was cutting corners — and putting patients at risk — to save money?

Good question. No one from the clinic is answering questions, and health officials did not make motives the focus of their investigation.

But it is clear that if anyone at the Endoscopy Center knowingly endangered patients, they committed a severe breach of medical ethics. State Board of Nursing attorney Fred Olmstead said Nevada law says licensed nurses and certified nurse assistants are obligated to report to the nursing board any wrongdoing at medical facilities. Failure to do so can result in revocation or suspension of nursing licenses or certification, he said.

Larry Matheis, executive director of the Nevada State Medical Association, which represents doctors, said “the first responsibility of every one of them is to patient care.”

The Nursing Board and the Nevada State Medical Board of Examiners are investigating and could revoke licenses, if necessary. Metro Police and the Clark County district attorney’s office are also talking about a criminal investigation.

Sun reporter Steve Kanigher contributed to this report.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy