Friday, June 20, 2008 | 2 a.m.

Sun Archives

- Get rid of pest? Not if it turns tap water pink (7-21-2007)

- Mussels now contained but need monitoring (1-18-2007)

- Lake Mead mussels identified as quagga, not zebra (1-13-2007)

They are so common they’re swimming in your spoiled milk, growing on the cheese left too long in the back of the fridge.

But if bacteria were about to be released into your drinking water supply, would you worry?

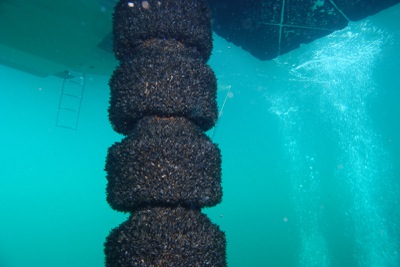

The Bureau of Reclamation says you shouldn’t. Its scientists want to set Pseudomonas fluorescens loose at either Hoover Dam or Davis Dam (near Laughlin) this fall as a cavalry charge in what has so far been a losing battle against the invasive quagga mussel. Quaggas, which can clog water intakes and damage pumps and other machinery, hitched a ride from their native Ukraine to the Great Lakes about 20 years ago and were found to be infesting Lake Mead last year.

Water authorities and power plants now use chlorine and other chemicals to rid pipes of the clinging critters. But the quaggas can recognize the chemical as bad for them, and when they do, they close up and often avoid ingesting enough of it to kill them, according to Pam Marrone, founder of the California organic pesticide company working on an alternative.

There are other drawbacks to using chemicals against quaggas, including the detrimental effects on the environment. Chlorine and similar chemicals also can form cancer-causing carcinogens when combined with organic matter in the water supply, according to Peggy Roefer, regional water quality program manager for the Southern Nevada Water Authority.

Enter the bacterium that guards against root rot in the typical garden plot. Turns out it produces a toxin that kills the quagga, and its equally troublesome cousin, the zebra mussel. Mussels feed on the bacterium and don’t realize it’s deadly until it’s too late.

Even dead Pseudomonas fluorescens kill the quagga, according to Dan Malloy, a research scientist at the New York State Museum in Albany who searched for the right bacterium for years.

He found the quagga killer to be harmless to several native fish and shellfish species tested, as well as to humans, Malloy said.

“We have been working with this bacterium for well over a decade. It’s everywhere. It’s already in the drinking water,” Malloy said, adding that his job is to work to preserve the environment, not pollute it. “I am a tree-hugger devoted to reducing the use of poisonous pesticides.”

In tests performed at New York power plants more than a year ago, the bacteria succeeded in killing up to 90 percent of zebra mussels and 70 percent of quagga mussels. And the bacteria may be even more successful at killing quagga and zebra mussels in the Southwest, because their kill rate is higher in warm, hard water.

Malloy and Marrone hope to begin testing the bacteria’s ability to kill quaggas in the region’s hydroelectric dam pipes this year, the next step toward developing a product that could be used commercially by power plants and water treatment facilities as soon as late 2009 or early 2010.

Marrone said tests wouldn’t begin on the Colorado River before this fall, and would be small. Still, they would be the first time the bacteria have been tested in the wild.

But Marrone admitted there are still several hurdles to overcome before testing could begin, including Environmental Protection Agency permitting.

The EPA extensively evaluates biopesticides before their approval to ensure safety for people and the environment, according to spokesman Dale Kemery. He said the process usually takes years and requires extensive scientific data for approval.

The EPA does issue experimental use permits. Officials met in March with representatives of Marrone Organic Innovations to discuss those regulations. The company has yet to apply for registration of its product, however, Kemery said.

Marrone’s company is still perfecting the recipe. The bacteria are grown in stainless steel vats, fermented like beer, for two days. The company will test different formulas, including pellets, liquids and powders. Marrone said it’s important that it not only be safe and effective, but also organic, because it will go into water that could be used at organic farms.

Marrone’s company is paying for development of the bacteria pesticide in part with a $500,000 grant from the National Science Foundation that it’s splitting with Malloy’s lab.

Marrone’s half of the grant will pay for tests on rats necessary for EPA registration. Her company will test the effects of the pesticide when inhaled, ingested and exposed to skin.

She said the company may ask states where it plans to test to apply for emergency exemptions, which would let Marrone to test the formula outside the lab sooner than would normally be allowed.

Exemptions are granted by the EPA, Kemery said, when another pesticide isn’t available to control a problem that is both sudden and poses “an imminent threat.”

Marrone said the tests might also be subject to state environmental protection laws.

Spokesman Dante Pisonte said the Nevada Environmental Protection Division would issue a letter of approval, rather than a permit, after consulting with state and federal wildlife officials and determining that the pesticide would not harm Lake Mead or its wildlife.

Malloy will use his half of the National Science Foundation grant, plus $100,000 this year from the Bureau of Reclamation, to determine whether the bacteria are also deadly to quagga and zebra mussel larvae, called veligers. The bureau expects to contribute $600,000 to $700,000 over three years to complete those tests, according to Dr. Kevin Kelly, a bureau scientist coordinating the laboratory tests with Malloy.

Fred Nibbling, an invasive species researcher with the bureau, said his agency’s first priority is getting quagga mussels out of its power plants. But he hopes Marrone and Malloy can come up with a formula that would kill quagga mussel veligers swimming free in Lake Mead and other parts of the Colorado River system, too.

And although some scientists say Malloy’s work is the most promising fix they’ve seen yet for the quagga, he’s not the only one searching for the perfect killer.

Roefer, water quality manager with the Water Authority, said the authority hosted a quagga mussel conference with 32 people, including 12 quagga experts, in April to discuss ongoing and needed research. Roefer said more funding is needed, though.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy