Associated Press

“We deal on a hope in teaching people to re-enter society. It’s hard to tell them, ‘It’s going to be so much better’ and then there’s less help out there.” Linda Lera-Randle El, executive director of Straight From the Streets, who has clients receiving annual payments from the Energy Assistance program and a half-dozen more who are waiting for replies to their applications

Wednesday, July 23, 2008 | 2 a.m.

Sun Archives

Beyond the Sun

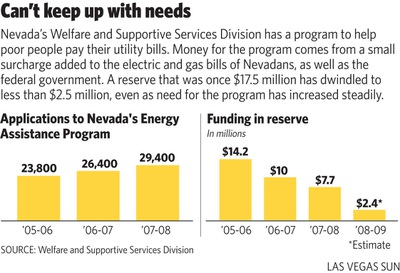

A state program to help poor people pay their utility bills is nearly broke, forcing it to limit the amounts it gives to Nevadans in need, just as that need reaches its highest point so far this decade.

The Welfare and Supportive Services Division’s Energy Assistance Program has gone from a reserve of $17.5 million only four years ago to a greatly thinned bank account of about $2.4 million. It has been spending more than it has taken in two years in a row, and applications were up 11 percent in the past year, with 26 percent more applications this June than during the same month of 2007.

“We’re at the other end of the spectrum and ... we’ve exhausted earlier resources,” said Lori Wilson, who oversees policy and budget issues for the energy program.

“We have to spread the money a little thinner over a greater population.”

Starting this month, the amounts the state will offer are limited based on each applicant’s income and the size of the utility bills.

The program is funded in part by federal grants, but most of the money comes from a surcharge added to utility bills — the “universal energy charge.” In Southern Nevada, the monthly surcharges typically range from 30 cents to 50 cents per month on electric bills and 14 cents to 21 cents on gas bills, Wilson said.

The assistance program originated in 2001 but got off to a plodding start. When the Sun caught up with it in June 2004, it had begun that fiscal year with $17.5 million in the bank and only about 7,000 households getting help.

“We’re here, we’re geared up, we have a lot of money and want to serve the households most in need,” then-administrator Linda Mercer said at the time.

Now nearly 30,000 households are seeking help from the state and face a backlog of two months for applications to be answered. Wilson noted that the increased need has not been accompanied by an increase in staff — she has received no additional caseworkers since 2006.

Linda Lera-Randle El, executive director of Straight From the Streets, a nonprofit organization that helps the homeless, found news of the program’s declining reserves and impending caps “frustrating.”

Since she learned about the fund in 2004, she has helped dozens of formerly homeless people obtain the benefit.

She has a handful of clients who get from $300 to $700 in annual, one-time payments from the program, plus another half-dozen who are waiting for replies. For people like her who help the valley’s poorest, she says it’s tough to keep up with program reductions and disappearances.

“We deal on a hope in teaching people to reenter society,” Lera-Randle El said. “It’s hard to tell them, ‘It’s going to be so much better’ — and then there’s less help out there.”

She anticipates that she and others will be seeing a wider range and greater number of people in need, given state budget cuts and the tanking economy.

“The way the economy is going, even working people are not going to be able to afford their utility bills,” she said.

Wilson said up to 30 percent of applicants are denied the benefit at present. Most of those who get it are elderly, disabled and living on Social Security benefits. Three-fourths are renters. More than half are at or under the federal poverty level, which is $10,400 for a single person and $26,500 for a family of four. She estimates that up to 45 percent of all households receiving the benefit will be affected by the new caps.

John Driscoll, a 67-year-old retired private school teacher, receives the minimum amount from the program for a single person: $180.

His monthly Social Security check is $1,083 and $425 of that goes to the rent for his downtown Las Vegas apartment. He used the last of this year’s energy assistance to pay last month’s electric bill of $70.

“Now I’m out of it until January,” he said with resignation.

And though Driscoll reapplies to the program every year, he confesses he doesn’t quite understand how the state determines what amount he should receive, or why.

Still, he has a suggestion for mending the situation. “Let them go back and raise taxes. That’s what they should do.”

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy