Sunday, Jan. 27, 2008 | 2 a.m.

Audio Clip

- Murren expects the slowdown to be short term.

-

Audio Clip

- Murren on effects of the slowdown and weaker dollar.

-

Audio Clip

- Murren talks about filling rooms and Las Vegas' good value.

-

Sun Archives

- As market gets tougher, CityCenter to sell in Dubai (1-24-08)

- Gambling on gaming stocks (1-21-08)

- Forecast: Silver State '08 (1-1-08)

There may be no place more calculating, more confident and with more swagger than Las Vegas, a seemingly invincible boomtown built on the finely honed skill of talking people out of their money and offering them nothing tangible to take home.

And then, some of those people move here to get a piece of the action — finding work at a casino or hotel, or building homes and high-rises, or erecting booths inside convention halls.

For decades, no U.S. city has boasted a hotter economy, sustained by workers in Armani suits, hard hats and aprons.

But stay tuned. We’re about to find out how resistant Las Vegas is to a downturn that some economists predict will become a recession.

We’ve weathered treacherous economies in the past, but this one will be different because of how we’ve economically matured into a somewhat different kind of place. Unemployment in the region already has increased by a third over the past year.

“It was easy for us to give ourselves high-fives when the economy was doing really well,” said MGM Mirage President and Chief Operating Officer Jim Murren. But now? “This is where we actually earn our money. It’s going to be tougher this year than it has in many years past and require a lot more work to deliver a similar performance.”

Flash back to 1991, when the nation faced a credit crunch, a housing crisis and a war in the Middle East. (Sound familiar?)

Gaming revenues suffered their steepest-ever one-month drop — a scare that led casinos to lower room rates to drum up business. New casinos such as the Hard Rock struggled with financing, and three other casinos filed for bankruptcy. Goodwill begged for donations to stay afloat, the unemployment rate rose, the governor laid off state workers and housing construction stalled.

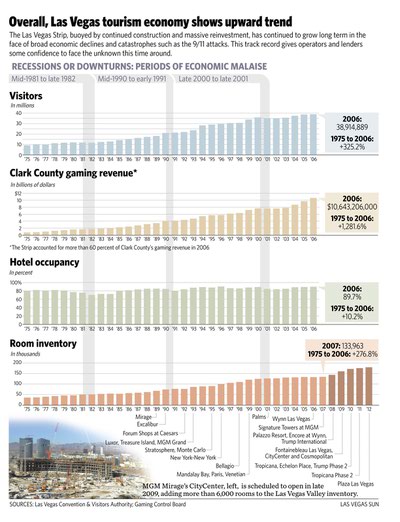

Still, Las Vegas survived better than most other places, with plentiful jobs that generated record growth and the promise of still more. Treasure Island, the Luxor and the MGM Grand were due to open within a few years, creating 42,000 jobs and adding 10,000 hotel rooms.

Las Vegas came away booming, and soon entered the era of the 90 percent-plus hotel occupancy rate it has maintained ever since. The experience bolstered Las Vegas’ image among residents and economists alike as a place that is, if not recession-proof, then at least recession-resistant.

Today’s Las Vegas parallels much of the 1990s model, given the billions of dollars of construction under way and planned for the Strip and the promise of 30,000 new hotel and casino jobs — triggering tens of thousands more jobs in the valley economy.

But today’s Vegas is also different from the Vegas of the past, and “depending on the severity of what the downturn is on the national level, Las Vegas is probably more vulnerable now than previously,” said Bill Eadington, an economics professor at UNR who studies the casino industry.

• The economy is twice as dependent on conventions for tourism growth as it was in the early 1990s. That could become problematic because employers are likely to cut back on sending convention delegates and providing expense accounts during downturns. (Already, MGM Mirage says bookings for conventions have slowed from years past and could flat-line for Las Vegas this year.)

• Las Vegas has become a more expensive place to play and live, discouraging budget travelers and prospective residents during rough economic periods.

• Visitors who do come are more likely to cut back on entertainment, dining and shopping than they are to stop gambling, even during tougher times. For the big Strip operators, who have invested hundreds of millions of dollars in nongaming amenities to widen Las Vegas’ appeal to folks who don’t gamble, gambling has become a minority revenue stream, making operators potentially more vulnerable to economic swings.

• The national housing crisis and the credit crunch are pummeling Las Vegas. We already lead the nation in the rate of foreclosures, and would-be homeowners are finding it hard to take advantage of plummeting housing prices because they can’t qualify for mortgages from an industry shaken by subprime loans.

New-home sales in 2007 were down 45 percent from the previous year to 19,670, the lowest number since 1995, while median prices were down 17 percent to $280,085 in the same period. Resales have been languishing on the market, with sales down 41 percent and prices dropping 12 percent from the previous year.

The downturn is taking its toll.

New housing construction has all but halted, with developers putting projects on back burners even as they squirm under big real estate loans.

About 4,900 construction workers were laid off in December, state figures show, and layoffs are occurring among mortgage lenders, real estate brokers, title providers and others. Entire offices have been closed.

We’re spending less — and sending state and local government budgets reeling from the drop in sales tax revenue. Furniture retailers, for instance, report sales down 12.1 percent last year through October from the previous year.

Unemployment has jumped to 5.6 percent from 4.2 percent a year ago.

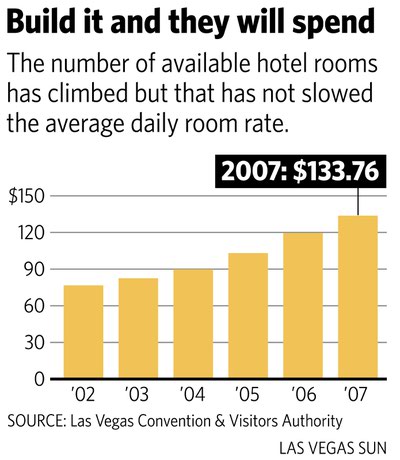

And even though hotel room rates have increased 11 percent over the year without dampening occupancy levels, the Cosmopolitan resort and casino is facing foreclosure as it seeks additional financing, and condominium projects are at risk as banks tighten loan requirements and force developers to put up more of their own cash.

Tourism numbers have remained relatively constant over the past year, as have restaurant sales — but what does that say for a town spoiled by years of steady, dependable growth, that considers less growth something of a failure?

Locals casinos are bracing for possibly their worst year because many of their customers are suffering from the poor housing market and rising unemployment. The two biggest locals casino operators — Station Casinos and Boyd Gaming, owner of the Coast properties — said they were holding their own through last fall, but they haven’t yet reported their earnings through the end of the year.

But there are components of the Las Vegas economy that might do well in an unfriendly economy.

One school of thought holds that the off-Strip properties will actually benefit as rank-and-file tourists rebel at the increasing rates on the Strip and look to the more affordable suburban resorts for their gambling entertainment.

Then again, the Strip’s strategies of reaching for the world’s wealthiest tourists, and nurturing a loyal customer base, may now pay off in spades, at least relatively speaking.

High rollers, especially from overseas — which provides a growing share of the tourism market and benefits from the weak U.S. dollar — may be largely shielded from a recession and still want to play here.

MGM Mirage’s Murren said, “The consumer is played out right now ... people are more guarded with their dollars. But we’re not really seeing that at the high end.”

In fact, his company, the largest operator on the Strip, expects to spend as much as or more than it did last year — up to $1 billion — on upgrades to existing properties, according to some estimates.

On the other hand, Harrah’s Entertainment, the world’s largest gaming company, is banking on its finely tuned gambler rewards program to drive business here, where it operates some of the most profitable and efficient properties in the business.

“The Las Vegas market has been stable throughout prior economic downturns except for the aftermath of 9/11,” Harrah’s executive Jan Jones said. “During that period our ability to draw Total Rewards cardholders from around the country to Las Vegas helped us outperform the market and avoid the massive layoffs that affected other operators here.”

Some people with a history in Las Vegas are downright optimistic about its ability to weather whatever comes its way.

Glenn Christenson, the former chief financial officer of Station Casinos who now runs a private investment portfolio, expects the housing market to right itself and consumer confidence to build.

“The local market has been soft relative to the past two to three years, but the market is still attracting new residents and jobs,” Christenson said.

“It reminds me of when the tech bubble burst and people were worried about their 401(k) plans,” he said. “The market rebounded quite robustly after that. People are still going to the casinos but spending less. I’m not sure whether it’s a six-month or 12-month phenomenon, but no industry ever goes in a straight line forever. This is a different challenge than we’ve faced in the last six years but I still think this is the best market to be in the gaming industry.”

Other financial observers aren’t pushing the panic button either.

“Until we see a full year of weakness on the Strip, you’re not going to see companies cut back on expenses or slow their growth,” said bond analyst Dennis Farrell of Wachovia Capital Markets. “The problem is, no one knows whether we’ve hit bottom or whether it will be a temporary blip or a bigger problem with the economy.”

Las Vegas does have something going for it. The people who run the Strip — and on whose successes the state depends — are savvy.

“They’re getting more creative about how they offset losses and fill in soft spots,” said Jim Medick, president of the market research company Precision Opinion, which conducts polls and research for casinos and other businesses. So, bottom line on Vegas and a souring economy?

“The feeling is that this is very real and we’re feeling it, but it’s OK, we’ll get through it,” said Kenneth Smith, principal with Glen, Smith & Glen Development, which primarily develops office buildings. “We’re not going into a big dark hole that nobody can see coming out of.”

Smith and others are counting on job growth fueled by new casino openings to ensure they don’t end up in that dark place. People will come for jobs. They’ll buy homes that are dropping in price. They’ll shop and eat out and demand services that will promote more economic growth. That’s what Vegas has done in the past, and there’s an expectation for it to happen again.

And in the meantime, we hang on.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy