Sunday, Jan. 27, 2008 | 2 a.m.

Murderabilia Web sites

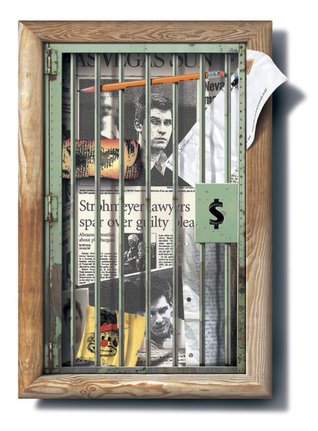

Ten years ago, convicted killer Jeremy Strohmeyer was one of Nevada’s biggest news stories, with coverage as aggressive as his crime was heinous: The teenager raped and murdered a 7-year-old girl in a Primm casino bathroom, and the case lived on in the media until Strohmeyer was sentenced to die behind bars.

Once the verdict sank in, Strohmeyer slipped into a prison cell and out of the collective consciousness. So what a surprise to see him again, older and online, posing shirtless in a Polaroid. How interesting to learn that his photograph, his poems, his prison envelopes and his porn collection are all available to you — for a price.

Somebody is selling Strohmeyer’s stuff, maybe with help from the murderer himself.

It’s not just stuff. It’s “murderabilia” — the personal belongings of convicted killers, sold by and for fans whom sociologists have dubbed “serialphiles.” These are people who want to own a piece of infamy, like a handwritten note from Strohmeyer, who, if collected like a prize, lives on forever through his things.

There are a number of online auction houses specializing in murderabilia, selling items of unusual appeal: hair clipped from Charles Manson; dirt from the crawl space where John Wayne Gacy hid his victims; school shooter Wayne Lo’s sperm left to dry on a picture of a pretty girl; a “fried hair” plucked off the floor under Ted Bundy’s execution chair.

The most prized of these items — such as a Gacy oil painting of his clown alter-ego, Pogo — can sell for thousands. Others, the gimcracks and gewgaws of killers with less cachet, sell for just a few dollars.

Photos of Strohmeyer sell for as little as $10. Racier items, like a rudimentary tracing of Strohmeyer’s genitals, sell for about $20.

This makes Andy Kahan crazy. Kahan is the director of the Houston Mayor’s Crime Victims Office and perhaps the most vocal critic of murderabilia. He’s spent years lobbying legislators and helping draft “notoriety for profit” laws that have criminalized the sale of such collectibles in California, Michigan, New Jersey, Texas and Utah. Now Kahan is working with Sen. John Cornyn, R-Texas, to pass a federal bill that would punish prisoners who use the U.S. Postal Service to mail any items for profit, effectively squelching much of the murderabilia trade.

The key to passing such legislation is not limiting what prisoners can do, the art they can make or the poems they can write, but rather limiting what they can sell. Otherwise, it’s a violation of First Amendment rights, which is exactly what got the 1971 “Son of Sam” law overturned. Designed to prevent serial killer David Berkowitz, and anybody else, from profiting from book sales, the U.S. Supreme Court determined in 1987 that the law was a violation of free speech protections.

So let them draw, or mail photos, or give away hair clippings, or whatever else they want to send, Kahan says, but don’t let them make a dime.

“From our perspective, it’s blood money, plain and simple,” he said. “There’s nothing more nauseating and disgusting.”

In this quest, Kahan has an unlikely ally: The Son of Sam himself.

Sort of like a hit man trying to keep his enemies close, Kahan spent the first part of his mission to end murderabilia actually buying the stuff, pretending to be a collector so he could get to know the dealers. He became so well-respected in the community of buyers and sellers that he, like any respected arts investor, started getting heads-ups from prominent sellers when something sweet was coming down the line. Kahan collected hair samples from five serial killers (Manson’s came formed as a swastika), fingernail clippings from serial killer Ray Norris, a pair of Lawrence Bittaker’s socks, a scrap of a T-shirt worn by Gacy and foot scrapings from “Railway Killer” Angel Maturino Resendez, among other items.

By buying, Kahan learned how the selling works: Dealers or collectors write letters to notorious inmates, hoping to start an exchange with them that will bloom into a relationship for profit. Although some dealers will work out a business arrangement with the killers they’re courting, others won’t say a word and will pose as friends while pawning off the prisoner’s goods in secret.

So Kahan started writing his own series of letters, informing a select group of felons that their items were being auctioned. Those who knew, and were using the kickbacks to stock their prison pantries, buy magazine subscriptions or help out family members, shrugged Kahan off. Those who didn’t know, he said, were outraged.

The Son of Sam was outraged. So now, any time Berkowitz gets a request for items from a dealer, he forwards it to Kahan for investigative purposes. Berkowitz has also appeared on national TV with Kahan, echoing his argument that murderabilia is, if not illegal, sick.

“It’s is a very strange and unusual alliance,” Kahan said. “But working with him is the absolute coup.”

Not everyone agrees. Murderabilia’s devotees defend their fascination by pointing to the countless TV shows and movies about crime and killing. Collecting, they say, is just an extension of a natural interest in the infamous, who are undeniably compelling.

Tod Bohannon, a math professor by day, runs one of the Internet’s most notable murderabilia sites, murderauction.com. He watched “Helter Skelter” at age 13 and was hooked. For weeks afterward, he bothered his parents about Manson, wondering how such a small person could command so much control. His parents, an attorney and a deputy sheriff, suggested that Bohannon write Manson, which he did. It was the beginning of a continuing correspondence.

Letter writing turned into collecting, collecting turned into dealing, and suddenly, Bohannon was running one of the best-known (and despised by Kahan) murderabilia auction sites. And if you don’t like it, he says, don’t visit.

“I just try to get to know the (inmates). To me, it’s neat. But it’s not like I am glorifying it,” he said. “I consider some of these people my friends.”

Ask him to scan the curio cabinet where he stores his collectibles, and he’ll tell you he’s got “a lot of hair, a piece of Ed Gein’s headstone, the last letter Manson sent me, a radio Gacy had in jail.”

Other items, his most cherished, he won’t disclose. Though Bohannon will say this: He hopes to be buried in his pair of Hillside Strangler Kenneth Bianchi’s cuff links.

Bohannon says most murderers actually “hiss” at the collectors who come calling, because getting convicted of a high-profile crime is “all the attention they want.”

Moreover, he argues, nobody is making a fortune selling scraps of paper or bits of cloth. If he were, then why would he continue to work 60 hours a week and run the site in his free time? And it’s not just the dealers who aren’t really profiting. Most criminals can’t receive large sums of money in the mail, and the income of others is taken as restitution. Those who do manage to make a few dollars, he says, often send the money to family members because it doesn’t buy much behind bars. And still others are simply afraid to sell.

“They don’t want the heat,” Bohannon says, “and I’m sure Andy (Kahan) is proud of that.”

Bohannon has a few letters from Strohmeyer in his collection, but he never put them up for auction. He’s never thought Strohmeyer “marketable” enough to sell.

The operators of a Web site selling Strohmeyer’s stuff, DaisySeven.com, denied requests for an interview. In fact, when DaisySeven proprietors discovered a reporter had successfully bid on a photograph of Strohmeyer, they refused to part with the item. An unidentified Web site representative then advised, also via e-mail, that the reporter not mention DaisySeven in any forthcoming story. Shortly thereafter, the reporter was described on the DaisySeven Web site as a “sneak.”

Strohmeyer may also be a sneak. Nevada Department of Corrections officials were unaware that his personal effects were being auctioned online, and subsequently advised their inspector general to investigate. Although it’s not clear whether Strohmeyer is breaking any rules, spokeswoman Suzanne Pardee said, “it obviously doesn’t feel right.”

Kahan, looking at the items being offered on DaisySeven, surmised that Strohmeyer had entered a partnership with a dealer and was aware his items were being auctioned. The shirtless photographs of Strohmeyer and the pages allegedly ripped from his pornographic magazine collection seem to have been solicited from the convicted killer, who is serving a life sentence in a segregated section of the Lovelock Correctional Center.

The investigation into the online sales of Strohmeyer’s stuff is ongoing. Meanwhile, the one-time teenage killer somehow lives beyond the bars, slipping little scraps of a life out of his cell and into the coffers of collectors — people who, though they say they see Strohmeyer as a fellow man, reduce him to a collection of trinkets, traded for fun. This is Strohmeyer’s real life sentence, the perversion that makes him a purchase before he’s a person.

“We immortalize these people,” Kahan says. “They are given infamy, and they become part of American capitalism.”

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy