Wednesday, Dec. 24, 2008 | 2 a.m.

Sun Archives

- Fewer citizen complaints put cops on beats (9-1-2006)

- Citizen panel alleges police wrongs (9-20-2005)

- Review board keeps subpoena power (1-27-2005)

- First year of Citizen Review Board yields 71 complaints (7-6-2001)

Allyn Goodrich, less than a year into his Metro career, made a rookie cop’s mistake: He saw a jogger trying to cross the road illegally, tried to stop the citizen with a short bleep from his siren speaker and instead activated the entire whooping alarm.

The jogger, Brad Dick, returned the favor with some choice words. Goodrich turned his car around, and the two argued. Afterward, Dick filed a complaint with Metro Police’s Citizens Review Board, an independent panel that investigates complaints about police misconduct.

And as complaints of police misconduct go, Dick’s was pretty minor. What wasn’t so minor, at least according to board members considering the case, was how one of Metro’s internal affairs detectives handled Dick’s complaint — by interviewing Goodrich in such a way it appeared he was helping a fellow cop, not pressing him for hard facts.

In a write-up of their findings, members of a Citizens Review Board hearing panel who investigated the issue, put it like this: “The interview of Officer Goodrich was so replete with leading questions and ‘questions’ which misstated prior testimony of Officer Goodrich that it raised questions in the minds of the panel members as to what was actually the subject officer’s version of the occurrence (as opposed to the interviewer’s version).”

Dick’s complaint became an investigation of a police investigation — a review board investigating the police who investigate police misconduct complaints. And this, beyond the fact an internal affairs investigation was allegedly so shabby, is the real story. It’s a sign, perhaps, the review board is evolving.

For only the second time in the board’s nearly eight-year history, internal affairs detectives were subpoenaed to testify before a hearing panel to explain their interview techniques. This was a real departure for the board, which has historically focused its investigations on the citizen’s accusation, the actual incident, rather than on Metro’s handling of the subsequent internal affairs investigation. This was a real departure for a board that can almost always be counted on to agree with the findings of internal affairs detectives.

Concerns about the way internal affairs investigations were being handled have been building for months, Citizens Review Board Executive Director Andrea Beckman said. Dick’s case was just the straw that broke the camel’s back.

But beyond these concerns, there’s something more significant: a board that is empowered enough, or bold enough, to investigate Metro’s investigators. And this change is a little harder to tease out.

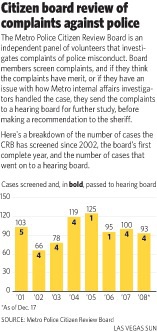

The board members are volunteers. There are 25, and they rotate on the board’s smaller screening and hearing panels. If the screening panel thinks the citizen’s complaint has merit, it can send the complaint to Metro internal affairs for investigation. Or, if internal affairs has already investigated the case, the review board can tell the detectives to reinvestigate it. Then it waits and sees what internal affairs detectives determine — essentially, was the complaint legit? Not legit? Impossible to prove or disprove? And did internal affairs detectives make the right determination?

More often than not — 89 times out of 93 for the year through Dec. 17 — the screening panel agrees with internal affairs, and the case is closed. When the panel has a problem with the detectives’ findings, however, it calls for a hearing panel to review the findings and make its own determinations. Those are forwarded to the sheriff for consideration.

In the Dick case, internal affairs detectives exonerated Goodrich in relation to both complaints filed against him; they concluded he did not misuse his siren and he did not act rudely toward Dick.

But the hearing panel disagreed: It said because there was no third-party witness, it was impossible to know whether Goodrich was rude. Instead of exonerating Goodrich, internal affairs should have determined the accusation was “not sustained.” This determination — we’ll never know what really happened — casts a shadow of doubt on the entire incident.

Another thing we’ll never know is just how leading the questions were. The transcripts of the interviews are private, available only to Metro and the review board, said Beckman, who has been executive director since the board was founded, in April 2000.

Metro, by the way, agrees with the review board’s findings. The detective who questioned Goodrich had been with internal affairs for about three months, and asked leading questions, said Assistant Sheriff Ray Flynn, who oversees internal affairs. The detective, whose name the department won’t release, has been counseled. Moreover, Metro’s legal staff will be giving internal affairs detectives a training session in questioning in February, at the division’s quarterly meeting.

“Internal affairs has a regular turnover and we need to address training deficiencies,” Flynn said. “We want to do as good an investigation as possible.”

To understand how the Civilian Review Board came to subpoena internal affairs detectives, to understand how the board found its teeth, start with who is on the board.

The board cannot include more than five former or current law enforcement officers, and in the earlier years, that quota was always filled.

There are only four former law enforcement officers on the board now; the terms of two expire in January. The five-person hearing panel that heard the Dick case included one former law enforcement officer.

Another difference in the makeup of today’s review board may be more important: Beckman says she has more academics, more citizen activists and board members who, overall, have more training.

The members are appointed by Metro Police’s Fiscal Affairs Committee, which consists of one citizen representing the public, two Las Vegas City Council members and two Clark County commissioners.

This means that when the board was founded, it was populated by volunteers appointed by the likes of then-Commissioners Dario Herrera, Lance Malone and Mary Kincaid-Chauncey, who were later sent to federal prisons on felony convictions.

And some of the earlier appointments were, perhaps, political.

They included people such as car dealership and casino owner Jim Marsh; George Togliatti, former director of the Nevada Public Safety Department; and John Hambrick, a former FBI agent, now a state assemblyman.

These days, however, instead of people such as Marsh, Togliatti and Hambrick, the board has UNLV professors Nancy Brune, Ray Patterson and Gregory Brown. Patterson is also director of the Boyd School of Law’s Saltman Center for Conflict Resolution.

“The appointments that are now being made are people who come from different walks of life. They are not necessarily people who made big contributions to politicians. They are people who are educated, involved in community activities,” Beckman said. “They are seeking out (volunteers) who they feel would be an asset to the board as opposed to someone who would like to put on their resume that they were on the board.”

Also, in the early days of the board, many members were retired. Today, the group, overall, is much younger.

So in those various ways, the membership is more balanced. And this is why Beckman thinks the board will be making a habit of investigating the internal affairs end of an investigation more routinely. Dick’s case could be the first of many for a group energized and confident in its ability to tackle all parts of a citizen complaint.

Flynn says the department welcomes scrutiny. He says the review board agrees with internal affairs the majority of the time, and so when there is an issue, the department takes it seriously.

“We’re not perfect,” he said. “We want to improve our system.”

Of course, the recommendations the board makes are nothing more than that — recommendations. And now that internal affairs has agreed with the review board, and decided that the second claim against Goodrich, that he was rude, should be found “not sustained,” it’s up to Metro managers to decide whether they also agree with the ruling, and whether they need to do anything more about it. This has yet to happen.

Still, even raising the issue, Beckman says, is a step in the right direction.

“Anything that improves Metro,” she said, “is our purpose in life.”

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy