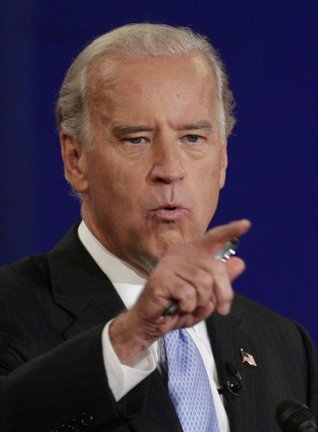

AP Photo

Joe Biden

Sunday, Dec. 7, 2008 | 2 a.m.

In a move to reassert Congressional independence at the start of the new presidential administration, the vice president will be barred from joining weekly internal Senate deliberations, Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid said in an interview with the Las Vegas Sun.

Reid’s decision to exclude Vice President-elect Joe Biden from the Senate arena where he spent most of his adult life is intended to restore constitutional checks and balances that tilted heavily toward the executive branch during the Bush presidency.

One of the most outward symbols of that power shift in the Bush years has been Vice President Dick Cheney’s attendance at weekly Senate Republican strategy luncheons. Cheney’s access to lawmakers enabled the White House to extend its reach into the legislative branch in ways unmatched in modern presidential history.

Congressional observers say Cheney’s presence helped create an atmosphere in which many Republicans favored party unity above congressional independence from the executive branch — perhaps most forcefully in debates over national security and the Iraq war.

“Cheney would come in there and try to force discipline on the Republican senators,” said Rutgers University Professor Ross Baker, who studies Congress.

“He was the Bigfoot that came into those meetings,” Baker continued. “If someone got out of line, he would put a thumb in their eyes.

“It’s something I think people will puzzle over for a long time — how passive the Republicans were, and how easily led they were by the Republican White House,” he said. “I don’t think that Reid wants a repetition of that at all.”

Reid, in an interview in his Washington office last week, said Biden would not be welcome to continue this tradition after he and President-elect Barack Obama take office.

“He can come by once and a while, but he’s not going to sit in on our lunches,” Reid said. “He’s not a senator. He’s the vice president.”

Reid’s decision signals the potential start of a new day in Washington, and a realignment of the executive-legislative relationship.

As the Bush administration comes to a close, Cheney’s tenure as vice president is regarded by scholars as perhaps the most powerful the nation has ever seen. He methodically acquired power for the executive branch that Republicans in Congress willingly ceded.

Cheney played a leading role in furthering administration policy, particularly in the national security arena — from the decision on 9/11 to try to intercept the hijacked airplanes headed toward Washington to the subsequent run-up to and prosecution of the Iraq war.

Cheney’s regular attendance, sometimes with White House advisers in tow, was unprecedented. Traffic in the Senate halls came to a standstill on Tuesdays as Secret Service agents cleared the way for the VP and his entourage.

A spokeswoman for the vice-president-elect said “Biden had no intention of continuing the practice started by Vice President Cheney of regularly attending internal legislative branch meetings — he firmly believes in restoring the Office of the Vice President to its historical role.”

“He and Senator Reid see eye to eye on this,” said Biden’s spokeswoman Elizabeth Alexander.

Reid’s decision to exclude Biden is one in a long line of Senate steps to swat away attempts by presidents and their proxies to insert themselves into the affairs of the chamber.

Most memorable may be then-Democratic Senate Majority Leader Lyndon B. Johnson’s attempt to retain his chairmanship of the party’s policy committee during his transition to vice president after the 1960 election.

As powerful as Johnson had been in the Senate, he generated fury inside his own party when he sought essentially to keep some control over the legislative branch from his new address.

Associate Senate Historian Donald Ritchie said Johnson was “hurt by the angry response.”

Senators then, as they had throughout history, understood potential encroachment of the executive branch on their power. Similar rebuffs fill the pages of Senate history, from John Adams to Spiro Agnew.

“Every vice president who has tried to be assertive has been restrained by the Senate,” said Ritchie, the historian. “Usually the vice president gets the hint and goes back to the White House.”

Reid has made no secret of his displeasure with the Bush administration’s reach into legislative affairs or his disdain for the expanded role of the vice president.

Reid is also aware of his own standing, including the criticism from those on the left of his party who have been disappointed the leader has been unable push back more forcefully against the Bush White House.

“The fact that the Republican senators acquiesced wasn’t a good thing,” Baker said, “and I don’t think Reid saw it as a good thing.”

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy