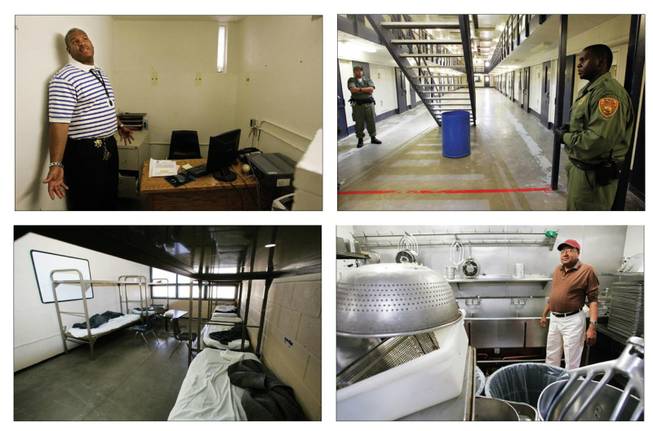

Top left: Warden Brian Williams shows a former cell converted to office space at the medium-security Southern Desert Correctional Center in Indian Springs. Top right: D. Hill, left, and J. Mason are among 198 correction officers at the facility that opened in 1982. It was built to house 714 inmates; it had 2,153 inmates in July. Bottom left: Once a classroom at the men’s prison, this space is now home to five inmates. It has no toilet, so a correction officer has to let inmates out to use the bathroom. Bottom right: Southern Desert’s kitchen manager Clarence King said his operation has not been upgraded as the prison population has risen steadily.

Sunday, Aug. 31, 2008 | 2 a.m.

Nevadans hold two values close: They are tough on crime, and tight-fisted with public money.

They can no longer be both.

A study by the Las Vegas Sun has found that those two values are today in stark opposition.

Tough sentencing rules adopted by the state a decade ago have today given Nevada one of the highest imprisonment rates in the nation. Nevada is paying to keep far more criminals behind bars, per capita, than most other states — at a cost of about $220 million for operations this year alone.

At the same time, the state is wrestling with a $1.2 billion budget shortfall. It is cutting money from schools, higher education, highways, social services and on and on.

“We’ve seen that being ‘tough on crime’ can be very expensive,” said Assemblyman David Parks, D-Las Vegas, chairman of a committee that examined the issue during the last legislative session. “We have to look at how we can be smarter in our approach to crime and punishment.”

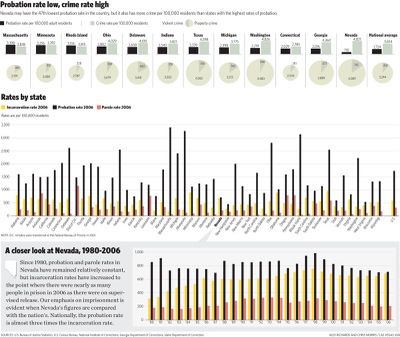

A Sun computer-assisted analysis of national data shows that in 2006, Nevada’s incarceration rate was the ninth highest in the nation while its probation rate was one of the lowest, ranking 47th.

Nevada’s probation rate in 2006, the latest available figure, was 710 for every 100,000 adult residents, barely more than one-third the national rate of 1,867, according to Justice Department and Census Bureau statistics.

Further evidence of the state’s failure to consider less expensive sentencing alternatives was revealed recently in a study conducted for the Nevada Advisory Commission on the Administration of Justice led by Supreme Court Justice James Hardesty. The panel is reviewing, among other things, the state’s truth in sentencing laws, which critics say do not give judges enough flexibility to keep nonviolent criminals out of prison. The laws were passed by the 1995 Legislature, following a national trend of imposing mandatory minimum prison terms and increasing the lengths of those sentences.

This lock-’em-up mentality took more criminals off the street and comforted crime victims and their families. But it also clogged the prison system and locked in skyrocketing costs.

Today, while other states have moved to place larger numbers of nonviolent offenders on supervised probation — at roughly one-tenth the cost of locking them up — Nevada remains focused on incarceration and is continuing to pay handsomely for it.

The study found that the number of defendants placed probation in the state has remained relatively constant over the past decade while the prison population has grown by leaps and bounds. In 1998, the study found, 12,561 people were sentenced to probation, compared with 13,538 in 2007.

As late as last year, critics charge, Nevada lawmakers were still pursuing a “bricks and mortar” approach to punishment, authorizing $332 million for prison construction to address crowding.

“We’ve made a big mistake,” said Clark County Public Defender Phil Kohn, a member of the advisory commission. “We just built hard walls. We didn’t build drug treatment centers and mental health centers to reach out to those people who aren’t violent and can be rehabilitated.”

Commission member Richard Siegel, president of the American Civil Liberties Union of Nevada, said the state would have been in a much better position to get through the current financial crisis if it had invested more wisely in the justice system.

“We could be shifting money to areas that we know are critical, such as mental health, education and health care for the poor,” he said.

One of the goals of the advisory commission, Siegel said, is to come up with recommendations this year as to how the Legislature can stop the runaway spending on prisons.

The Nevada Corrections Department estimates it costs $20,678 a year on average to incarcerate someone. The state has not calculated the average cost of supervising someone on probation. But its Parole and Probation Division, with a budget this past fiscal year of $45.5 million, supervised roughly 19,500 probationers and parolees. That averages out to $2,333 a year for each person under supervision.

But the cost of supervising a probationer is less than that because the probation division does much more than manage caseloads. Among other things, it prepares pre-sentencing reports for district judges. The department investigates each defendant’s background and recommends a sentence. It can recommend probation, too, when a defendant is eligible.

Defendants most likely to be eligible for probation are those convicted of nonviolent crimes, including burglary, larceny and other property crimes and drug offenses.

In 2006, however, a large number of inmates — 34 percent of the men and 60 percent of the women — were imprisoned for nonviolent offenses, according to the latest data from the Corrections Department.

If those percentages were the same as of July 31, when prison officials said they were housing 13,072 inmates, a total of 4,698 inmates would have been incarcerated for nonviolent crimes.

And though some of those inmates could have pleaded down their offenses from violent crimes or have had prior violent offenses, that figure, along with the maximum $2,333 cost per probationer, provides a means of comparing the annual costs of probation and incarceration.

It would cost taxpayers $97.1 million to house those 4,698 inmates at $20,678 each. The cost of putting those people under supervised probation would be, at most, $11 million — saving $86.1 million a year. That’s more than the cost of running the Southern Desert Correctional Center in Indian Springs and the Florence McClure Women’s Correctional Center in North Las Vegas — for two years.

Even if half of the property crime and drug offenders had a violent past and were ordered incarcerated, taxpayers would save $43.1 million a year.

“This is something the citizens expect us to look at before we raise taxes,” said state Sen. Bob Coffin, D-Las Vegas, a longtime Senate Finance Committee member. “If it’s true that our best intended legislation has worked against us, then we need to make a change.”

Other states are ahead of Nevada, according to corrections consultant William Burrell, New Jersey’s former state court probation chief.

“The trend among the states is to find other options than prison for drug offenders and low-level property felons who are not a great risk of creating a violent offense,” Burrell said. “They’re looking at things like shorter sentences and more community-based supervision. For drug offenders, they’re mandating residential drug treatment. Research is more than sound on the matter that community treatment works.”

The savings in Nevada could easily be spent on other needs. After about 90 vacant probation officer positions are filled, there would be enough savings left to increase the number of substance abuse treatment beds, to add transitional housing to ease inmates back into society and to beef up job placement services for parolees and inmates who have finished serving their time.

“Nevada has one of the worst social safety nets in the country,” said Assemblywoman Sheila Leslie, D-Reno, administrator of Washoe County’s drug and mental health courts. “We don’t provide adequate services for mental health or substance abuse, which are the main reasons people commit crimes and go to prison.

“When people get out of prison they often have nowhere to go. So we have to make sure that during this transitional period that they have a place to live. They can make new acquaintances, get a job and a fresh start. Otherwise, we’re setting up people to fail.”

While Nevada’s adult population has tripled since 1980, records show that the number of inmates has increased nearly eightfold, from 1,740 in July 1980 to 13,072 in July. The prison operations budget likewise has ballooned from $16.8 million in 1980 to $257.8 million this past fiscal year. That budget, however, was slashed by $48 million to help the state get through its economic crisis.

Even Howard Skolnik, the Corrections Department director, acknowledges the state’s lock-’em-up mentality has come back to bite it financially. It stems, in part, from an outdated approach, he explained.

Historically, large numbers of offenders going through the prison system here were people who committed crimes while passing through Nevada, so the state did not feel obligated to develop social programs to assist them. But in recent years, as more offenders with roots in Nevada began showing up in the system, that attitude changed, Skolnik said.

“We’re headed in the right direction,” he said. “We just have a lot of ground to make up.”

In the meantime, Skolnik, who also is a member of the justice administration advisory commission, strongly defends the record $332 million in prison construction spending the Legislature approved last year.

Much of that funding is going toward a 1,200-bed expansion of the High Desert State Prison in Indian Springs and a 300-bed addition to the Florence McClure women’s prison in North Las Vegas.

“I don’t want to find Nevada in California’s situation, where the courts are involved because of overcrowding,” Skolnik said. “I have a responsibility to maintain a safe and secure environment for staff and inmates. I can’t do that if we begin cramming inmates into facilities without more space.”

Skolnik said there is plenty of proof Nevada’s prisons are bursting at the seams.

The medium-security Southern Desert Correctional Center in Indian Springs for men is one example. Opened in 1982, designed to house 714 inmates, its population as of July 31 was 2,153. All cells are a mere 6 by 10 feet, designed to hold one inmate each, but all are double-bunked today.

Prison Lt. Minor Adams said roommates will sometimes fight — and cause problems for correctional officers — thinking they can get some “alone time” by being sent to a separate isolation unit. But double-bunking has occurred in that unit, as well. And one of the isolation cells is now being used as a disciplinary hearing room because of a shortage of space for staff.

Recreation rooms for inmates are furnished with double bunk beds to help with the overflow. Classrooms, visiting areas and even the prison chapel also are short of space. The dining area is so small inmates often stand with a full food tray for 10 minutes before they can find a seat.

For Warden Brian Williams, the headache of managing the crowded facility doesn’t go away.

“We never get enough staff,” Williams said. “I have 198 officers and I could use 260. If you look at my facility, they’re packing ’em in.”

With Nevada ranked as one of the country’s most violent states on some national surveys in recent years, not everyone in law enforcement here is unhappy with the way the incarceration system is working.

Clark County District Attorney David Roger is among those who believe authorities are putting the right offenders behind bars.

“People have to work real hard in the state of Nevada to land in prison,” Roger said. “We don’t send first-time offenders to prison and often we don’t send second- or third-time offenders unless they commit a heinous crime. The Legislature will have to make a difficult policy decision in 2009,” Roger added. “Do they fund additional space or reduce the prison population? If they reduce the prison population, there’s a substantial risk crime will go up.”

Much of the debate in the Legislature will focus on the effects of the 1995 truth in sentencing law and related acts that toughened punishments for drug trafficking and created additions to sentences for factors such as being a gang member.

Justice Hardesty said the advisory commission is preparing a number of bill drafts in an effort to persuade the Legislature to change the way the state approaches incarceration.

Sometimes in Nevada, Hardesty said, the punishment doesn’t fit the crime.

One example, he said, is the state’s definition of a drug trafficker, which can include anyone caught with as little as four grams of a controlled substance, an amount equal to four packs of Sweet’n Low. He cited the hypothetical example of a young man paid $150 to drive a car with drugs from Sacramento to Nevada, where he gets convicted as a trafficker even though his only role was driving.

“Is that what the Legislature intended, or were these sentences intended for the guy who paid the driver $150?” Hardesty said.

How successful Hardesty and other advisory commission members will be in persuading the Legislature to change its thinking remains to be seen.

The Legislature has a 23-year history of shelving the recommendations of such commissions.

Some of the people on the latest advisory commission tried to get lawmakers to understand that just building prisons isn’t enough to curb the crowding, but they couldn’t get past the money committee chairmen, who held the belief that the public prefers offenders to be behind bars.

The advisory commission is expected to incorporate into its recommendations several of the 2002 findings of the largely ignored last blue ribbon panel that studied the corrections system.

That panel discovered that Nevada was far behind more forward-thinking states.

It first learned that Nevada was placing twice as many inmates in costly maximum- and medium-security prisons than the national average, and was one of the few states without a community corrections strategy focused on putting supervised inmates to work outside prison.

The panel also found that 72 percent of individuals on parole or probation who were ordered to attend revocation hearings because of new crimes or technical violations were sent back to prison.

“Nevada should establish non-incarceration intermediate sanctions for offenders so Parole and Probation can better manage ‘technical violators’ in the community without returning them to prison,” the committee concluded. “Nevada currently has no community-based facilities to handle ‘technical violators’ or those who might benefit from some level of supervision, but not full prison incarceration. Every other state in America has facilities of this kind, and Nevada would also benefit from these cost-effective options.”

The state also lacked sufficient prison programs, substance abuse treatment, education and employment opportunities to prepare inmates for successful release into the community, the panel found.

And it pointed out that transitional or reentry housing for inmates was even more limited.

Advisory commission members said these findings are still relevant.

“We’re very much on the same page as that 2002 report,” the ACLU’s Siegel said. “The real question is whether anybody is going to listen at the Legislature.”

Advocates for change are optimistic and have found a key ally in influential Senate Majority Leader Bill Raggio, R-Reno, chairman of the Senate Finance Committee.

“In view of the budget crunch,” Raggio said, “those recommendations will be looked at very seriously, as long as we’re not turning out violent criminals and sexual offenders.”

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy