A year and a half after a labor union put Anishya Sanders front and center in a federal legislative initiative, the single mother is homeless and unemployed.

Friday, Aug. 8, 2008 | 2 a.m.

Audio Clip

- Anishya Sanders on promises made to her by union representatives.

-

Audio Clip

- Sanders talks about union leaders toasting to her promising career at a dinner in Washington, D.C.

-

Audio Clip

- Sanders on responses she got from representatives when she was out of work.

-

Audio Clip

- Sanders talks about setbacks that resulted from her involvement.

-

It was a long fall from the fine dinner and shots of Belvedere vodka at one of Washington’s premier steakhouses to the Motel 6 on Fremont Street.

Anishya Sanders is still brushing herself off, and wondering what’s next.

The 35-year-old single mom is unemployed and homeless, selling food stamps for cash. Her children live hundreds of miles away. This isn’t the outcome she expected when she agreed to be a union’s mouthpiece in a high-profile campaign to reform labor law. Her union, she said, had promised her protection, a job, a better life.

She’s still waiting.

Make no mistake: the Laborers’ International Union of America is still singing her praises for helping its cause. But as for the reward of a better job for her efforts? Well, the economy isn’t cooperating.

Sitting on the worn-out couch of a friend’s apartment in a rough patch of North Las Vegas, Sanders holds back tears and buries her head in her hands, searching for ways to explain — to friends, to family, but most of all to her five children — how her life has boomeranged.

•••

Sanders moved to Las Vegas in October 2003 from Pasadena, Calif., to be close to the grandparents who had helped raise her between stints in foster homes. Sanders’ mother was a drug-addicted prostitute, she said.

Crime had become a way of life for Sanders as well. By her 30th birthday, she was a five-time felon, mostly because of counterfeiting and forgery scams. But when her fifth child was born in the infirmary of Valley State Prison in California, Sanders “woke up,” she said.

In Las Vegas, five children in tow, Sanders sought to begin anew. “I didn’t want to be a statistic,” she said. She held various part-time jobs before contacting the Urban Chamber of Commerce for direction. She enrolled in a two-month training course for highway workers offered by the Nevada Transportation Department. Her children became latchkey kids.

In August 2004, she landed a job as a traffic flagger with All Pro Traffic Control, making $11 an hour. The pay wasn’t much, but with some creative financing it was enough to rent a modest town house. Work went well and Sanders said she quickly became a favorite in the workplace. Some contractors, she said, requested her by name.

Still, with five children to feed, the money wasn’t enough and in 2006 Sanders couldn’t make rent. She sent her four young sons to relatives in California while she and her daughter moved into a small one-bedroom apartment in a gritty downtown neighborhood.

It was about then that the Laborers’ International Union of America entered her life. Union organizers told Sanders the laborers could deliver better wages — $18 an hour — and health care benefits. “They promised me in an aggressive fashion that I would be OK,” Sanders said. “I soaked up everything like a sponge.”

Organizers, she said, started using her name in conversations with other All Pro workers. Soon the union had authorization cards from 17 of 23 employees and filed for an election with the National Labor Relations Board. But All Pro refused to recognize the union and fired two workers. Management, Sanders said, awarded raises to some employees and intimidated others. Workers filed unfair labor practice charges against All Pro with the federal labor board.

Enter the Change to Win labor federation. The All Pro organizing effort dovetailed with the federation’s national campaign for the Employee Free Choice Act, which would make it easier for workers to organize and stiffen penalties for employers who retaliate during unionization drives.

On its Web site, Change to Win featured Sanders as one of several “working men and women who have courageously stood up for the American dream.” Sanders spoke out against the company. “We work hard for All Pro and we want the company to succeed,” she said, according to the federation’s Web site. “But this should be our choice. We are not being recognized and we are being disrespected by not getting any benefits, including something as simple as bathroom breaks and lunch breaks.”

The response within the labor movement was tremendous, Sanders said. Within All Pro, however, management wasn’t so enthusiastic. Sanders said her supervisor told her — off the clock and over drinks — how disappointed she was and that further involvement with the union would likely mean termination.

Change to Win had bigger plans though. In February 2007, it flew Sanders to Washington for a week. On the schedule: attending a news conference with congressional Democrats to support the new union legislation, which was set for a vote in the House. The federation gave Sanders $300 for new clothes and another $300 to compensate for lost wages.

The federation put her up in The Madison, a swanky, four-star hotel a few blocks from the White House. “It was beautiful. I didn’t touch a door the entire time,” Sanders said. “I was Ms. Sanders. I thought, ‘Do they really know where I come from?’ ”

She and others told their stories at a news conference that included Rep. George Miller, chairman of the House Education and Labor Committee. Sanders then lunched with leaders from the international Laborers union at the National Democratic Club.

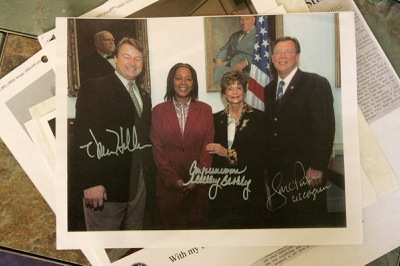

Afterward, she returned to the Capitol building where she met with Nevada Rep. Shelley Berkley. The two spoke in the congresswoman’s office for 20 minutes before Berkley left for the House floor to vote on the bill. She used her time there to tell Sanders’ story.

The bill passed the House overwhelmingly (it later died in the Senate) and union officials took Sanders to Bobby Van’s Steakhouse to celebrate. Sanders had never tasted anything like it: surf-and-turf, glasses of merlot. And then there was the union, with news of another job, a union job paying $18 an hour and offering health care benefits.

“It was like a storybook,” Sanders said. And a far cry from the foster homes, ghettos and prisons that had come to define her 34 years. After three years and a number of false starts, Sanders’ life finally seemed on track. The table toasted with shots of Belvedere.

When she returned to Las Vegas, she said, the union put her through steward training in anticipation of the promised new job.

In the meantime, she continued working at All Pro, where the organizing campaign had all but flamed out and her hours were reduced. Co-workers were told not to talk to her, she said. “My name was a cuss word there.”

Two months later, Sanders said, she was assigned to a road job in a remote part of the valley. She said she turned it down because she had no way of getting there — and the company fired her for “no show, no call.” According to Sanders, George Vaughn, the head of Laborers Local 702, told her to file charges with the federal labor board, seek unemployment and, failing that, welfare.

Sanders said she was frustrated she still didn’t have the promised new job and called the international officials she had met on her Washington trip. Those officials, including the Laborers international president, contacted Vaughn, who soon had $800 in member donations for Sanders, she said.

By now the National Labor Relations Board was responding to All Pro workers’ earlier charges. It found All Pro officials had threatened, intimidated, interrogated and ultimately fired workers who supported the union. About two weeks later, All Pro signed a settlement agreement with the labor board, pledging to honor federal labor law in the workplace.

The local found a job for Sanders, at a demolition company.

But the work, which paid $16 an hour, lasted only a month. When the job was complete the workers were laid off.

The local told Sanders there were few jobs to be had, and those that existed required “muscle.” She called Washington, and again Vaughn provided money — $400, which came from his own pocket.

But Sanders said what she really wanted was a job, any job.

Weeks of no work turned to months, and Sanders said she called Vaughn again. After she vented for a few minutes, Sanders said Vaughn told her, “Your 15 minutes are over,” and hung up. When Sanders called back, she said, a receptionist told her there was no work — and even if there were, she owed dues money.

The local to which Sanders belonged has since been absorbed into a larger Las Vegas affiliate.

“She did want a permanent job in the construction industry. I’m sure that is something a lot of people would want,” said Jacob Hay, spokesman for the international Laborers union. “But the nature of the construction industry means jobs come and go ... (Local leaders) helped her out to the extent that they could, but when it came down to it there weren’t any jobs available that matched her set of skills.”

Sanders has been unemployed since June 2007. “I’ve been everywhere,” she said. “You practically have to give a DNA test to get hired at KFC.”

Sanders said her criminal background has made her a pariah and “as an employer, I would think the same thing.”

After being evicted from her second apartment last year, she moved into a friend’s house that had gone into foreclosure. When the constables arrived to evict them, Sanders sent her 15-year-old daughter to live with her grandparents and rented a room for herself at Motel 6 on Fremont Street.

She ran out of money and now she and her daughter share the spare bedroom of a friend’s North Las Vegas apartment. The other children remain in California.

Sanders is angry at the union for breaking what she saw as its promises after she put her job on the line for its sake.

“I allowed the union to dictate every move. I made a change to win and I lost,” Sanders said. “I was a celebrity. They made me believe I was in it for the long haul. It was too good to be true.”

Hay, the union spokesman, said: “Everyone really appreciated her help at the committee hearing. She was the star of the show. There just weren’t jobs at the time that matched her skill set.”

More than a year after Washington, Sanders has little more to show for the experience than souvenir photographs. There’s one with Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid, signed, “With My Best Wishes.” There’s another with Nevada’s House delegation, including Reps. Dean Heller and Jon Porter, both of whom opposed the union legislation. And there’s one with Terence O’Sullivan, international president of the Laborers union.

“We look so happy,” Sanders said, flipping through the photos. “I call it the 15 minutes of fame. Now I don’t have an explanation for friends and family.”

By telling her story, she said, she hopes “to open up some ears. I just want to work.”

“If my daughter looks at me like I looked at my mother,” she said, leaving the thought incomplete. “I just want better for my children.”

And then: “They should have just left me alone. I would still be working at All Pro.”

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy