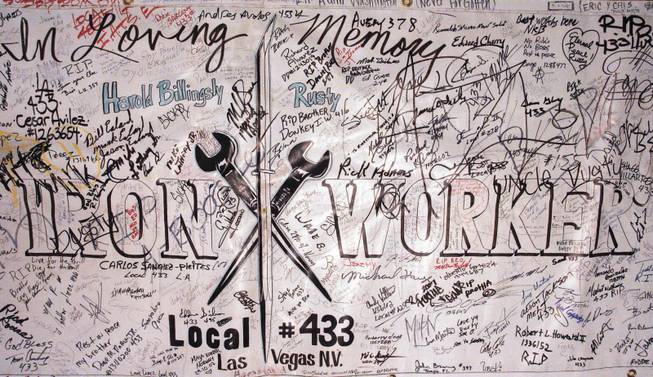

Construction workers who knew or worked with ironworker Harold “Rusty” Billingsley signed this memorial banner after he died last year at the CityCenter site.

Tuesday, April 1, 2008 | 2 a.m.

The disturbing rash of worker deaths at casinos, condos and hotels being built along the Strip raises safety issues that must be addressed, safety engineers and others say. But making fundamental changes in the culture of construction safety in go-go Las Vegas will be tough.

“It’s not going to happen, not in this city,” a safety engineer for a large general contractor said Monday, speaking on condition that he would not be identified. “It’s push push push.”

In the midst of its $30 billion-plus growth spurt, nine workers have died in eight accidents at CityCenter, Cosmopolitan, Fontainebleau, Trump and Palazzo. That’s equivalent to the number of worker deaths reported during the entire 1990s Strip building boom.

As the Sun reported in stories Sunday and Monday, investigations by the state’s Occupational Safety and Health Administration found patterns of safety violations by contractors that include failing to ensure workers are properly trained, allowing them to use faulty equipment and leaving them exposed to falls by not covering or guarding holes in decking or placing temporary planks or netting below.

Many of those findings were later overturned during informal conferences between employers and OSHA administrators. Contractors succeeded in arguing that the workers themselves were responsible for or contributed to their deaths.

The deaths have prompted discussions at union halls, contractor offices and construction sites.

Many workers say speed is the main underlying cause: Crowded work sites, pressure to finish work quickly and fatigue from extensive overtime lead to unsafe conditions, they say.

Construction safety experts for labor and industry-related organizations say the fatalities and safety violations indicate that safety planning and oversight are not high priorities for contractors in Las Vegas. If safety were emphasized more, they say, research indicates that projects could be completed just as fast.

“It’s a management leadership issue,” said Emmitt Nelson, a former construction manager for Shell Oil who has conducted research for the Construction Industry Institute. “It’s related to how well you’re doing your preplanning and whether you’re putting too much emphasis on production.

“I don’t think you can say categorically that a project is too fast,” Nelson said. “You just have to make sure you’ve got the process right.”

Business agents from ironworkers union locals outside Nevada became concerned about safety practices in Las Vegas after the November death of David Rabun Jr., the third ironworker to die in 16 months.

That led to the intervention of Greg McClelland, a representative of the California-based Ironworkers Labor Management Cooperative Trust who recently began convening a safety advisory group made up of union representatives, general contractors and subcontractors.

Most large general contractors on the Strip are participating, including Perini, which oversees construction of CityCenter and Cosmopolitan, adjoining sites where six workers died in little more than a year.

“The point was to say, ‘We’re all in this together,’ ” McClelland said. “We needed to make sure everybody is on the same page and we all understand what we need to be looking out for.”

So far, the committee has discussed some specific fixes — more training, for example, and getting apprentices to wear an “A” on their safety helmets so that they’re easier to identify and oversee.

Another suggestion is to watch for fatigue among workers. Many are putting in 70 or 80 hours a week, working without days off, contractors and union representatives say. Recent studies show that heavy overtime in construction can lead to more injuries.

“One of the steel companies has identified that it needs a person who’s designated to just walk around the project talking to the men to identify those men who are fatigued,” McClelland said. “They would say, ‘Go home.’ ”

But contractors may be in a bind: They depend on workers to put in the overtime to finish the projects on the tight schedules they are contractually bound to meet, McClelland and others said. If the project is delayed, there are almost always hefty fines.

“To get a realistic, workable, safe schedule, you have to talk about the pressure from owners,” McClelland said. “It’s a tough sell.”

McClelland wants general contractors to agree on safety and scheduling provisions when they bid on projects and when they accept bids from subcontractors, even if those provisions mean the job takes longer to finish.

“We want a uniform standard that contractors will agree to in their contract,” McClelland said.

If everyone agrees to the same standard, he said, owners will be forced to slow down projects if that’s what is necessary to do the job safely.

But that position has met resistance, and safety engineers on the committee say they have little sway at their companies.

“Most of us are (at our companies) because it’s mandated to have safety people, not because we have any clout,” said the safety engineer who wished to remain anonymous. “I’m constantly telling the project managers we need to slow the pace down, but they say the owners won’t let us do that.”

Steve Holloway, vice president of the Associated General Contractors of Las Vegas, which is made up of general contractors, says they are unlikely to agree for fear they will be underbid by a company that agrees to do the job faster.

Instead, he says, contractors are talking among themselves about how they might schedule projects differently to improve safety and reduce the need for constant overtime without delaying the completion dates.

“You might not start two buildings right next to one another in close proximity,” Holloway said. “You might wait until one is almost finished to start building the other, to spread it out. You also could, for example, find a way that doesn’t make the ironworkers work overtime on several projects in a row.”

MGM Mirage spokesman Alan Feldman said his company is willing to discuss changes in time frames on future projects they put up for bid, although it isn’t convinced that a strong correlation exists between construction schedules and safety.

Plus, he said, general contractors should already be factoring in safety when they bid for a contract.

“Any professional contractor ought to be looking and making a serious and sober and realistic assessment of what it’s going to take to do a job,” Feldman said.

Safety experts from the construction industry and unions argue that the key is better oversight and more emphasis on safety by general contractors.

The Construction Industry Institute, made up of several large contractors and property owners (Perini is not a member), has extensive research showing that it is possible to prevent injuries regardless of the size, scope and speed of projects. It also has studies showing that injury-free projects can be completed faster.

The crucial factor, said Nelson, the former Shell construction manager, and others is for contractors to do enough planning and to keep up a mantra of safety.

That translates into safety meetings every day before the job begins, and then mini-safety training before every task workers perform. In each meeting, supervisors should write down the tasks and keep records.

Contractors also should investigate even minor injuries in search of underlying safety problems, the Institute says.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy